Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Paul F. Murphy: Playing Universally

Paul F. Murphy: Playing Universally

All About Jazz: Music is your life—you've been playing drums since you were five years-old and performing publicly since age 12. Outside of being what you do, how does music and drumming effect you? What is music to you?

Paul F. Murphy: More than any other art form, I believe music is the best tool for defining and exploring the human soul. It is the most essential mechanism available for the exploration of man's consciousness, spirituality and creation. However, it's not like other tools you can hold because music is in the air. It is the closest thing you can assimilate to the spirit. In using this tool, one finds themselves on a path that is not necessarily predictable and not necessarily self-righteous. However, if you continue down that path, you will find truth.

As far as drumming goes, I like to experience all different types. I draw from each distinct mode of playing, my own interpretation of drumming. However, I don't consider this as a defining of drumming. I consider myself an explorer of sound and the effect that sound generates through and on human emotions.

AAJ: Why is it important to you to examine the relationship of sound, the human spirit and emotions?

PFM: It is important because it causes one to look up instead of at the space they are in; to look around instead of only examining their own self-existence. I believe the process and the results allow both the artists and the listeners to touch different aspects of the human condition as well as the universe on both a physical and spiritual plane without any physical travel—similar to meditation but meditation is not felt by others.

AAJ: What do you believe you are accomplishing as this kind of explorer and catalyst for self-assessment?

PFM: Finding my own inner-self and, in a very small way, trying to find my relationship to both the physical and metaphysical universe and the creator. If you are anywhere and you look up to the sky, you see stars and patterns. It's true you can sit there and say there was a big explosion and this just happened. And, what is the likelihood that all these patterns we see in the sky, earth and nature—the patterns that keep occurring—just happened. I don't think you would see so much repetition of patterns—patterns that are models of structure, growth and directions. And, from looking at the little that man has built on this planet, it seems as though something greater has built this universe—which I don't think anybody is arguing against because the patterns repeat throughout everything we can see from within ourselves and without ourselves and as far as we can see with man\-made tools of magnification. So, I would like to try to assimilate some strand of connection for why I am here on this planet. And, has anything I've done on this planet helped to change how anyone thinks about anything? With that, there are going to be positive and negative speculations and critiques. Just like protons and electrons in an atom; the most basic structure of the universe. Through my drumming, I hope that some may see my most positive thoughts about mankind's existence. That is what I try to express in my playing. That is why I don't set up structures or parameters when I play. Not doing so allows for the exploration of any structure, which leads to the discovery of new directions within my own way of thinking—my own thought patterns. I am literally trying to interact and play in the most spontaneous setting available while creating music that a child or an intellectual will enjoy and understand.

So, I would like to try to assimilate some strand of connection for why I am here on this planet. And, has anything I've done on this planet helped to change how anyone thinks about anything? With that, there are going to be positive and negative speculations and critiques. Just like protons and electrons in an atom; the most basic structure of the universe. Through my drumming, I hope that some may see my most positive thoughts about mankind's existence. That is what I try to express in my playing. That is why I don't set up structures or parameters when I play. Not doing so allows for the exploration of any structure, which leads to the discovery of new directions within my own way of thinking—my own thought patterns. I am literally trying to interact and play in the most spontaneous setting available while creating music that a child or an intellectual will enjoy and understand.

AAJ: You've said before that the best way for tapping into this type of exploration and discovery process and for harnessing the ability to make meaningful statements in your playing is through intense practice and soloing. You start to discover things about your playing and about yourself. You find, not only methods of deep expression, but significant expression while soloing without set parameters and blocked patterns. I feel like this type of practice has absolutely unlocked a lot more of this thought process for me. It's led me to a higher ability of expression and, hopefully, a greater understanding of playing and thinking altogether.

PFM: Right. And you wouldn't have been able—and weren't able—to do that by only thinking about it from your point of view. You had to learn how to tap into a bigger picture. You also had to learn how to get outside of whatever box there is around the common mode of thought and playing that was projected onto you as a student before.

AAJ: Absolutely. Getting outside of the box was the biggest thing playing-wise: finding a way to conceptualize playing differently and hopefully uniquely; creating instead of reproducing; playing something as opposed to just playing the drums. And, in order to do that, finding a way to connect playing to something other than playing ...

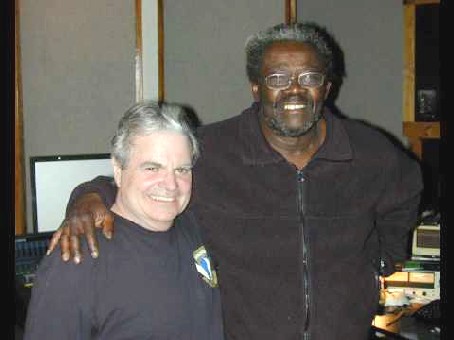

PFM: Finding a way to draw the connection to the universe and the human spirit and condition. From left: Paul Murphy, Larry Willis

From left: Paul Murphy, Larry Willis

AAJ: What has helped you understand the universe and the soul to allow you to connect your playing with these things?

PFM: I would say my love of drumming has always outweighed my lust for financial gain and that has allowed me to keep my mind open and clear and sustain a pursuit of knowledge and skill. I have also found that family has become more and more important and influential. I decided long ago that I was going to be far better off studying, playing and recording what I believed in instead of living in a situation where I would have probably ended up dead.

AAJ:Did this decision allow you to pursue and study music and drumming to a higher level?

PFM: My current job as associate director of Georgetown University facility management and operations allows me to live a stable life in an environment surrounded by the study of humanities and technology. It allows me to be as free-thinking and playing as I need to be—or want to be. I still practice every day. I still play and record the best of my musical endeavors with my best friend, Lawrence Elliot Willis. And, I teach extremely selectively.

AAJ: The ability to be free and forward thinking is very important. It seems as if that mindset is basically required in order to be a part of—or even conceptualize—the kinds of things you are talking about. And that mindset is always a part of the path to innovation. Being considered a pioneer in music and drumming, what qualities do you believe are necessary to be an innovator?

PFM: An innovator has to do at least one of two things: you can either advance concept or you can advance style. You have to change or move one or both of these things in a new direction. And it takes belief. You have to believe in what you are doing, you have to be determined to do it. Motivation, determination and continuous pursuit are a huge part of success as an innovator and success in general, but success does not necessarily equal innovation. Success often defines commercialism—not all the time—but in order to be new, you have to think new. You have to think and be outside of the box.

I believe, too, that technique is the mother of invention. Technique and the study of techniques are what lead to innovation. It doesn't just happen. You need to have an understanding of all the world's music and what makes them different and the same. In order to advance style, you must have a good functional knowledge about past and current styles and in order to advance concept you must understand past and current conceptual movements.

AAJ: "Technique is the mother of invention." Clear examples of this are players like Jimmy Lyons, John Coltrane, Dewey Johnson, Walter Davis Jr., John Tchicai, Jaki Byard and Clifford Jordan, all of whom you have played and/or recorded with and all of whom are viewed as innovative players who changed and/or contributed to the progress of jazz. Each of these players had/has a serious command of their instrument. Can you talk about the process of developing your technique to get to that kind of level? PFM: Well, I studied for 11 years with Joseph Levitt, who was at that time, the principle percussionist of the National Symphony and director of the Peabody Conservatory of Music. Throughout the years, during my study with Levitt, I was introduced to Gene Krupa, Louie Bellson, Buddy Rich, Max Roach, Philly Joe Jones...

PFM: Well, I studied for 11 years with Joseph Levitt, who was at that time, the principle percussionist of the National Symphony and director of the Peabody Conservatory of Music. Throughout the years, during my study with Levitt, I was introduced to Gene Krupa, Louie Bellson, Buddy Rich, Max Roach, Philly Joe Jones...

AAJ: Not only met but played or studied with.

PFM: Right. I also spent a lot of time playing all different forms of music from symphonic to orchestral to marching to R&B and rock and roll. At the age of 17, I was introduced to bassist Billy Taylor, from Ellington's band who was instrumental at a very important time in my development as a player and the direction I would end up taking in music.

AAJ: What happened in the development of your technique "beyond?"

PFM: Sitting in a parking lot outside the Blair Mansion Inn, where I was playing a society gig with Billy [Taylor] and pianist John Phillips, while sitting in Billy's 1965 Ford LTD, Billy stuck in an 8-track cartridge and asked me, "Do you know who these cats are?" We listened for about 25 minutes. I said no, he told me, "This is Cecil Taylor, Jimmy Lyons and Sunny Murray. These are the cats you need to know. This is what you play."

AAJ: What put you as "one of those cats?"

PFM: My concept of playing time; the way I moved time.

AAJ: What was that concept?

PFM: I was able to give the feel and swing of bop without continuously using the 4/4 typical-designed ride cymbal, hi-hat, bass and snare patterns. I was able to create the same feel while shaping the space to my needs and patterns. It's weird; I'd been playing with that cat for like a year and a half. He never went, "Man, you can't play bop." He just said these are the cats you need to meet. They do what you do. He also told me, at that time, I was not ready for New York City. He said I needed to play on the West Coast. So I did, I moved to San Francisco.

AAJ: When or how did you begin developing that playing style?

PFM: It was something that I came upon or into while continuously playing with guitarist David Davenport. He was a very gifted and forward-thinking guitarist who's playing was a cross between Pat Martino and Frank Zappa. I mean, Dave and I would do this thing where we would say we are going to play 64 measures at a slow tempo and stop on beat one of the 65th measure. There came a time where we were both stopping on one while playing totally free—while knowing where the original time was. We started off by going 12 measures. Then, when we got that, we tacked on another 12, then another and kept going.

AAJ: Is this something you just did without ever hearing the avant-garde players?

PFM: Umm, yes, but the more I listened to hard bop cats, the more I heard people playing "loose." So it wasn't like I thought that it was something we were pioneering.

AAJ: So, this playing style does not come from an uninformed point of view, which is clear from your years of study with Levitt, Krupa, Bug, Bellson and your playing experience spanning several types of music. What kind of theoretical applications are within the "free?"

PFM: In this environment, theory is applied more in a sphere than as points on a graph. Current music theory is all being based on an X and Y flat graph when because of current dissonances, re-modulations and synchronizations of the spreading of vibrating objects, the plot for coordinates is at least 3-dimensional. This 3-dimensional sphere is what I'm most concerned about exploring. As well as the possibility that a connection to a fourth dimension isn't sometimes made. This is something that I was aware of and different players were telling me that I was doing.

AAJ: Can you explain what the "sphere" is?

PFM: I believe the sphere is a miniature model of the universe. Everything here is flat—the floor, the wall, that house, the water. The sky gives some illusion as not flat. But, once again, when you look up, you see the planet Earth is just a big pool of space. Take all directions out from the Planet Earth and draw them in, you get a sphere—something that doesn't begin or end. There can be a top and there can be a bottom, but there doesn't have to be. In that sphere, the directions of motion and the alternatives to motion are endless. You can be moving and you can be stopped. You can be playing and you can be at rest. You can all be going forward. You can all be going in reverse or against each other or you can cut across. At the same time, as an ensemble, you can stop and create space or you can go in several other directions. As long as everybody is listening and contributing to the ensemble, you are creating a living, breathing organism, which not only affects the listener but also develops your understanding of sound, motion and rest. It all can be as one or simultaneously diverse. But it's all contained and exists within the sphere. The energy and thought process all exist within a 4-dimensional sphere.

AAJ: The "sphere" encompasses each component of the music as something that isn't necessarily as cut and dry as typical staffs, bar lines and theoretical ideas suggest?

PFM: The intersections of melody, harmony and rhythm within time and space sometimes create a sound or idea that had not been preconceived, played or intended by the artists. A very basic example of this was the discovery of two notes vibrating in dissonance, which created an audible third sound and was later termed "ring modulation."

Ring modulation is an example of a surprise discovery which led to extensive investigation by not only music composers but scientists, physicians and governments as well. Certain musicians took it upon themselves to learn how to produce linear patterns by using these center tones of ring modulation. Others incorporated circular breathing as well as the playing of more than one instrument to create the effect. The creation of the effect may be considered a discovery as well as a gift. It is certainly innovation. The linear exploration would be the creating of a concept and the use of that concept through composition would become a style.

As a result, you have the breaking or advancing of concept and style—the two things necessary for innovation. The tones produced by ring modulation created harmonies that had not been used or explored in any great detail. This same energy has now been used in all forms of music, throughout the sciences, as well as by technocrats and governments. Some examples of this are Stockhausen, sonar and the cloaking or stealth innovations.

As a result, you have the breaking or advancing of concept and style—the two things necessary for innovation. The tones produced by ring modulation created harmonies that had not been used or explored in any great detail. This same energy has now been used in all forms of music, throughout the sciences, as well as by technocrats and governments. Some examples of this are Stockhausen, sonar and the cloaking or stealth innovations.

For the first time, the blending of two sounds generating a third and the documenting of this phenomenon opened a study of energy and sound that has existed since man has occupied the earth—or even before. However, it hadn't been discovered until someone documented or harnessed it—even just a little bit. The point is, it has always existed—man's recognition and understanding of it took thousands of years.

For anyone to say that the study of energy has been nothing more than scratching or touching the surface is the same as saying that the depths of musical composition have all been discovered and explored. And, if the possibilities of composition have not all been discovered or explored, who's to say that they can all be contained or explained by current methods of music theory. However, a strong knowledge and comprehension of composition and theory should be obtained before any worthwhile results are to come through free improvisation. Rashied Ali.

Rashied Ali.

Examples of the understanding as well as the blending of sounds, although subtle, are very evident in the duos that were performed and recorded by Jimmy Lyons and myself during the CBS and RCA sessions I led in 1982 featuring Jimmy, Dewey Johnson (from the John Coltrane album, Ascension (Impluse, 1965)) on trumpet, Karen Borca on bassoon and Mary Anne Driscoll on piano and voice. These concepts are also captured on the current works I am recording with Larry Willis. More often than not, when someone listens to an improvisation by Larry and myself, their first comments are usually something like "this sounds like more than two musicians."

The exploration of sound blends within the concept of free-form improvisation, eliminates the constraint of written composition and allows the interpretation and interpolation of one's mind and thought process to be recorded as a statement instead of a commercial quest.

AAJ: You told me before, when you toured with Jimmy and his band people went the "craziest" while you and Jimmy played as a duo. You have done a lot with duos: Lyons, [Joel Futterman, Willis. Is there something about duos that you believe helps capture the sphere, ring modulation and other concepts you've talked about?

PFM: Nah, I actually believe it's financial constraints that create the duos.

AAJ: So, there's no particular preference for a duo?

PFM: Well, I mean, as a leader, first of all you have to attempt to put the artists in a setting that is conducive for thought, reflection, playing and documentation. To assemble more than three or four people for several days in one place and then to afford to be able to record them and pay them for their time, travel and lodging are all responsibilities that must be assumed by a leader.

I have had very long and intuitive discussions about the difference between sidemen and leaders and the promotion of art in general. A very dear friend of mine, with whom I've had a relationship with for over 30 years, posed a question to me while we were having dinner after attending the Kabuki Theatre in Manhattan. The question he asked was, "do you want to be my sideman or do you want to be a leader?" My answer was, "I want to be a leader." Cecil Taylor's response to me was, "the road you have chosen is going to be very difficult. However, you will meet many wonderful people and artists and have great interactions along the way."

Which brings us back to the point of why duos and trios are most often found in the realms of the avant-garde jazz world. I believe that the exploration and musical endeavors of Larry Willis and myself would be far more accepted with the addition of a horn player and a bassist with the level of knowledge and experience of Ron Carter. This combination of musicians and sound would be a landmark in a world surrounded by the sound of contrived jazz. There have been landmark recordings as well as milestone producers. I believe we have created a step forward in present day jazz and it would be very helpful if we had a producer, the financial backing and promotion comparable to that which is given to professional athletes. The producer would have to be someone that is willing to step outside the box and create the environment that Creed Taylor provided years ago for the CTI label. I believe there is enough money in the world to allow myself and others to be financially sound enough to devote our time to playing music and developing art without constraints.

I believe that the growth of knowledge and the understanding of music must take place on all levels from 21st Century studies of classical composition through all cultural tradition as well as commercial rock and roll, folk, blues and country. I also believe that within the structure of the world there should be a much larger percent of radio time and stations—or whatever methods of mass dissemination that allow for exposure on a grand scale—available to artists that are not playing music for the sake of financial gain.

In the late 1970s and throughout the '80s, an interesting fusion was taking place in the lower east side of Manhattan. Within a thousand feet of each other, some of the most experimental jazz was being played at a club called the Tin Palace. Groups like Cecil Taylor, the Jimmy Lyons Quartet, Rashied Ali and many others often played there. Then, at CBGB's, there were groups like The Dolls, Adam and the Ants, Mink DeVille, The Fleshtones and Patti Smith. At that point in my career, I was managing Ali's Alley, owned by John Coltrane's drummer, Rashied Ali. I was also playing in the Jimmy Lyons Quartet and had my own group with Jimmy, Dewey [Johnson], Karen [Borca], Jay [Oliver], and Mary Anne [Driscoll]. After closing the Alley at night, Rashied and I would usually head over to the Tin Palace and Joe Lee Wilson's club, the Ladies' Fort. From there I would drop by CBGB's and listen to what was happening on the punk rock scene. Two very close locations existing in the same time and space both producing energy that would change both traditional jazz and rock and roll forever. Both of which didn't seem to be commercial pursuits. Henry Rollins, from the band Black Flag, who has been very successful in rock and roll and Hollywood, hosts a worldwide radio broadcast where he features all forms of music. To his credit, he also continues to keep alive spoken word, where he discusses politics, elitism, social revolution and the existence of love throughout the world without the continued prodding of the warring class that continues to promote chaos and depression.

Henry Rollins, from the band Black Flag, who has been very successful in rock and roll and Hollywood, hosts a worldwide radio broadcast where he features all forms of music. To his credit, he also continues to keep alive spoken word, where he discusses politics, elitism, social revolution and the existence of love throughout the world without the continued prodding of the warring class that continues to promote chaos and depression.

I have had the opportunity to travel the world and have found that most human beings are content to live in peaceful coexistence. The justification for this statement and the examples are the works of art that have been preserved through the centuries and which continue to be produced, presented and in some cases restricted from popularity because of their promotion of free-thinking and the defining of the human condition.

If 20th Century classical, country, folk, punk, rock, jazz (in whatever form) and the numerous forms of other world music can all coexist, then how hard is it for the people of the world to demand from our leaders that continents should be farmed instead of mined and that the exploration of our world and universe should be a harmonious global effort. The people of the world are able to coexist. It is the elitists who seek total control, power and self-satisfaction at the expense of the masses. And, it is those same elitist people that have produced the living conditions throughout the planet. The existence of technology, intellect and love of the human spirit make for a far better existence than our world leaders have set forth.

AAJ: The study, appreciation and promotion of art put this on display.

PFM: Yeah.

AAJ: By promoting free thinking and exhibiting peaceful coexistence and, in cases like yours, exploring the condition of the human spirit and mind, art demonstrates a model of harmony and a standard of living that should be demanded by the people.

PFM: Right. Take for example the microcosm of Haight-Ashbury in the 1960s. There all art, all races, all people, all music and all literature were embraced. The coexistence of peace within itself sparked innovations such as the Haight Street Free Clinic and all forms of music from the Jefferson Airplane to Miles Davis. This offer and presence of peaceful coexistence was answered by the city fathers of San Francisco with Kent State. What does that tell you? I believe there needs to be a greater amount of public access to art. I would like to see more institutions made available to the public in the form of education. I believe that the most refined and most endowed venues of education have now and will always have the ability to study music and other art forms, however, access to these institutions is difficult at best. During pre-college years, there should be programs developed to not only teach music theory, composition and art, but also more ... well, let's just say, if you're a kid that plays flute and wants to study flute, where do you go? Peabody?

I believe there needs to be a greater amount of public access to art. I would like to see more institutions made available to the public in the form of education. I believe that the most refined and most endowed venues of education have now and will always have the ability to study music and other art forms, however, access to these institutions is difficult at best. During pre-college years, there should be programs developed to not only teach music theory, composition and art, but also more ... well, let's just say, if you're a kid that plays flute and wants to study flute, where do you go? Peabody?

There has to be the same access to resources for people who don't have the financial ability to go to places like Harvard and Peabody. Those people need to have places to study and obtain the knowledge needed to produce art and think freely. What we are doing right now is keeping the pool very small. If we broaden the opportunity for learning as well as the candidates for learning, progress is going to come and come at a much faster rate. I mean vibrations, tones and rhythms can make children younger than 3-years old stop in place and dance because voice and drums were the primal instruments from the beginning of time. If sound has the ability to do that to someone that is totally "innocent," then what is to say that the study of vibration, sound, tone, rhythm, etc., doesn't have something to do with astral projection or other methods of transportation, growth and peace that are not currently considered by hard science. They obviously exist if a three year-old child stops and dances when feeling and hearing these vibrations and tones.

AAJ: So, by opening up real opportunities for more than just the elite to learn about and produce art we increase the chances and pace of new discovery altogether?

PFM: Yeah.

AAJ: What do you have to say about the programs that are presently available, accessible or not, for teaching music and art?

PFM: I believe the programs that are set up now are devoted to method and not exploration. The reason we listen to Beethoven's Fifth over and over and over and not to Alban Berg, Stravinsky or Stockhausen is because of the methodology used in promoting certain sound and composition over others. The media takes the choice out of music.

AAJ: To go even further, what is the content that is being taught and how does it affect the way people play and write? Most students' first experiences with drum curriculum were all based off of patterns—set blocks of patterns to practice, which lead to certain sounds. If these blocks of patterns are taught, learned and practiced by all drummers—which isn't too far off the mark—then those certain sounds come through in all of those people's playing. So everyone ends up sounding very similar—if not given the tools necessary to expand these ideas.

Furthermore, due to the structure and ways of presentation, representation and explanation, what is to be played becomes locked into a grid, like you talked about earlier. A grid where everything must be played this way, it must fit this way. It's very mechanical. As a student trying to do what you are told and believe is going to make you a better player, it is very easy to get boxed into sounding like everyone else.

Furthermore, due to the structure and ways of presentation, representation and explanation, what is to be played becomes locked into a grid, like you talked about earlier. A grid where everything must be played this way, it must fit this way. It's very mechanical. As a student trying to do what you are told and believe is going to make you a better player, it is very easy to get boxed into sounding like everyone else.

But you teach students to look at music and drumming as something that is not dictated by a grid and a metronome and doesn't necessarily fit firmly between any lines—bar or otherwise.

PFM: And that's what it is and that's how it should be taught. A good example of methodology and the removal of choice is the use of click tracks, auto-tune and quantization on all commercial recordings. The click track and quantizing and the other allow commercial music to be recorded by people who may or may not be able to play or people who may or may not be able to sing.

AAJ: There are a lot of things happening in the studio that allow people who are not competent players or singers to sound good. And it doesn't end in the studio. They also use live digital enhancement techniques to make bands sound good that would otherwise be sub-par— it's called "sweetening." Why have we allowed these sorts of things to go down?

PFM: Money. They are making money off of it. And most people don't know, I guess.  AAJ: Not only is there the idea that modern day methods of teaching music fail to produce new, forward thinking and innovative artists but perhaps that we are being taught that past innovative composers and artists did things in a way that they might not have. Meaning these artists were working within the confines or in a set way that isn't necessarily true . . .

AAJ: Not only is there the idea that modern day methods of teaching music fail to produce new, forward thinking and innovative artists but perhaps that we are being taught that past innovative composers and artists did things in a way that they might not have. Meaning these artists were working within the confines or in a set way that isn't necessarily true . . .

PFM: Meaning that if Beethoven was such a great innovator—and he was—then why are we still playing Beethoven's Fifth without any innovation and the way that somebody wrote it down after the fact. When the Boston Pops play Beethoven, the lead instruments play with no innovation, and, as Beethoven was a great innovator, why are we playing Beethoven the same way day after day, month after month, year after year. I don't think Beethoven would be into that. The printing press has allowed the penning of music through the use of a staff and bar lines. Melodies are not thought of or written with the use of bar lines. We have to think beyond and sustain and resolve our musical gestures and the archivist of music will supply the staff and bar lines.

Because of the invention of the printing press and current educational methodologies, musical notation has become simplified, whether it be a linear, melodic or horizontal chord structure idea to be read and understood. This has allowed music to become accessible for many living in our civilization. It has also created a pattern of writing compositions that can be defined and understood but creates a box. It has also offered very little explanation or knowledge of how to attain feel. I ask our musicians of the future to have a solid understanding and perception of the box but also to have the innovation and thought to think and play outside the box as well as to learn how to project the human emotion of the heart, which is feel. You must be able to swing.

Selected Discography

Paul Murphy/Larry Willis, Foundations (Murphy Records, 2009)

Paul Murphy/Larry Willis, Exposé (Murphy Records, 2008)

Paul Murphy/Larry Willis, Excursions (Murphy Records, 2007)

Paul Murphy Trio, Shadow * Intersections * West (Cadence, 2004)

Paul Murphy, Enarre (Cadence, 2002)

Paul Murphy/Joel Futterman/Jere Carroll, Breakaway (Cadence, 2000)

Trio Hurricane, Suite Of Winds (Black Saint, 1986)

Jimmy Lyons Quintet, Wee Sneezawee (Black Saint, 1984)

Paul Murphy Quintet, Cloudburst (RCA, 1983)

Paul Murphy/Jimmy Lyons, Red Snapper at CBS (CIMP, 1982)

Photo Credits

Pages 1, 2: Lion Fox Studio

Page 4: Courtesy of Paul F. Murphy

Pages 3, 5: Seana Carroll

< Previous

Reclamation

Next >

News? No News!

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.