Home » Jazz Articles » Opinion » On the Banks of the Jabbok With Chet Baker

On the Banks of the Jabbok With Chet Baker

Bloom: ... I may, as I say, lack trust in the covenant, but though I keep asking Yahweh to go away, I say so many times in this book, he won't go away. He haunts me.

NPR: You really want Yahweh to go away?

Bloom: Yes, I would love him to go away, but he won't.

NPR: He wakes you up at night.

Bloom: He wakes me up at night.

I suffer from the same suspicion and want of a cut-and- dried understanding of trumpeter/singer Chet Baker (1929 -1988) as Professor Bloom did of his Yahweh. I want to simply dismiss Baker as a self-indulgent hack who recorded so much music, for so long, supporting of his famous heroin addiction that at least some of it had to be good if not exceptional, while the vast majority was marginal if not downright bad. There exist legions proclaiming Baker as that wounded bird, pouring out his emotions through his trumpet or singing; a poor reader, he simply grabbed musical pathos from thin air by his sheer will and spun gossamer tales of loss and longing and was a pretty decent guy to boot. Conventional wisdom assumes the chemically dependent, and, be sure, Baker was chemically dependent, with no emotions—only that hard calculus of synthetic need with little or no capacity for empathy outside of that. These disparate views cannot possibly reconcile, can they?

In a media world where reality TV shows like VH1's Celebrity Rehab with Dr. Drew and Sober House, and A&E's Intervention portray chemical dependency intervention, treatment, and recovery in discreet bundles, 44 minutes each, Chet Baker would stick out like poorly plumbed needle marks. A modern Werther, beautiful and doomed, Baker was a recalcitrant junkie, resistant to any type of rehabilitation, save for methadone (and that's not rehabilitation). He unfortunately outlived his youth and the era it existed in to become a musical coelacanth, floating through time-out-of-mind like smoke from a cigarette.

Baker was the poster child for the stereotypical addict: selfish, untrustworthy, reckless, and rootless. He was at it so long and paid so much dues for his lifestyle that he lost the spoiled, self- indulgent whining that made Celebrity Rehab de rigueur opiate addicts Tim Conaway, Steven Adler, and Mike Starr so unsympathetic. On that note, forget about Lindsay Lohan and Charlie Sheen, a junkie of Baker's caliber should give Drew Pinsky sugar-plum dreams of the perfect media patient for his above mentioned cotton- candy carnival show, to which Baker would have laid waste and Pinsky, spinning his hypothetical failure his way, saying "It's a consequence of the disease; they cannot all be saved."

In a disease characterized by dishonesty, in a very strange way, Baker found an honesty about himself and his furtive demand for the acceptance and enabling by others that most junkies never achieve because they don't live long enough. The people who dealt with Baker were those in complete acceptance of his addiction and its consequences (and their endurance of same): the trumpeter showing up late or not at all; the threat of marginal or even bad playing; and all of the other baggage that goes along with the yen. These people would have been labeled "enablers" or "codependent" or some other pop A&D contrafact from the 1980s. Yet, Baker's keepers accepted it all as fixed overhead. The thing that made Baker the object of such dense codependency was what filmmaker Bruce Weber called his "damaged beauty," an absolutely pregnant metaphor too big for this tome. And then, of course, there was the music.

A (mostly) functional heroin addict from the early 1950s until his death at 58 in 1988, Baker was able to do as he pleased, which was mostly get loaded, by always adopting a path of least resistance and learning never to get attached to anything, except temporarily to those benefactors who gladly enabled him. At the end of his life, Baker performed and recorded just enough, with anybody in any venue and for anybody to stay flush in his medicine. Because it is the nature of addiction, Baker had little regard for anyone or anything, save for the drug. Heroin, and not music—and certainly not his family—was the driving force that propelled him at the end of his life. To consider anything else is both romantic and naive, and there were many who embraced this.

Chet Baker was light on a lot of things. He did not have formal musical training or an expansive musical vocabulary, he did not have a high range in his trumpet playing, he did not have vibrato in either his singing or blowing. But worst of all, he totally lacked the good fortune to die young, leaving a spectrally vibrant Romantic image. Instead, Baker showed us ourselves in a decades-long slow-motion train wreck, falling down the stairs of a burning building, highlighting the results a life of taking the long slide: rootless, baseless, and alone.

Chet Baker was light on a lot of things. He did not have formal musical training or an expansive musical vocabulary, he did not have a high range in his trumpet playing, he did not have vibrato in either his singing or blowing. But worst of all, he totally lacked the good fortune to die young, leaving a spectrally vibrant Romantic image. Instead, Baker showed us ourselves in a decades-long slow-motion train wreck, falling down the stairs of a burning building, highlighting the results a life of taking the long slide: rootless, baseless, and alone. But what about the music? Ah, there is the quandary. While Baker went all Dorian Gray before our eyes over thirty years, from the almost feminine matinee idol beauty to the desiccated, shabby Baroque death mask, he remained, at a very high level, capable of producing compelling jazz, that complex and often densely improvisational art. It is an enduring dilemma that we often consider Baker only in the context of himself, comparing the different performances, both live and recorded, across the expanse of his 40 performing years. Baker attracts positive and negative criticism like a celebrity black hole— the artist as hero and antihero. When considering Baker, you consider no one else.

However, the view from 30,000 feet (and 25 years since his death) reveals something much different. In reality, Baker was something more than a footnote and something less that a seminal artistic force in jazz. His narrative has provenequally as important and compelling as his music, something that the similar chemically- circumstanced Art Pepper was able to escape, if only partially, in the period before his death in 1982. For good or bad, Baker's repertoire and approach changed little over his career and that seemed okay as he always maintained a core following (particularly in Europe) that were ready to eat him with a spoon on the off chance, specifically at the end, that Baker had a "good" night.

Since the turn of the century, there have been three biographies of Chet Baker, not counting his "memoire" As Though I had Wings (St. Martin's Press, 1997). Jeroen de Valk published his near hero- worship Chet Baker: His Life and Music (Berkeley Hills Books, 2000), providing a good survey of Baker's discography, which was no easy task considering the profligacy with which Baker recorded to continue his lifestyle. De Valk's notes on Baker's more important recordings, particularly those recorded shortly before his death, are excellent.

The second biography to come along was James Gavin's Deep In A Dream: The Long Night of Chet Baker (Knopf, 2002). Gavin chose to focus on celebrity and its cost for the unprepared. Deep In A Dream deals very little with Baker's musical legacy, while focusing on the evolution of his visual and behavioral image as a modern day morality tale gone very, very wrong. Gavin has been roundly criticized for being hateful to his subject and rendering a one sided account of his life. Nothing could be further from the truth. Baker made his bed, not Gavin. What Gavin did was to compose a Late Romantic tone poem to the dark heart of the American Romantic Dream, that dream that houses the myths of John Henry, "Doc" Holiday, Edgar Allen Poe and Charles Foster Kane. Should one want an example of wanton character savaging, I direct them to Albert Goldman's Elvis (McGraw Hill, 1984) and The Lives of John Lennon (William Morrow & Co., 1988). Those were, in the words of Greil Marcus, cultural genocide.

One of the results of Gavin's biography was a push by other writers to provide more balance to Baker's life picture. One such effort is Matthew Ruddick's excellent Funny Valentine: The Story of Chet Baker (Melrose Books, 2012). In his prologue, Ruddick noted that one editor's response to Lisa Galt Bond's proposed (and never published) Baker biography, Hold The Middle Valve Down was that Baker's life was "too much of a downer to make a commercially successful book." Television, like the aforementioned Intervention and Addiction, would indicate otherwise if his media was expanded (the consuming public's practical illiteracy and allergy to reading is a matter for another time). The word for this behavior is schadenfreude, pleasuring one's self with the misfortunes of others. And, Baker had many of those.

Ruddick agreed with the editor, regarding Gavin's book. While admitting that "The book was very well researched, drawing on a large number of original sources...it was ultimately a depressing story, a tale of squandered talent and a harrowing descent into drug addiction." Well, that is exactly what Baker's story was and is and Gavin never claimed to capture anything else but the very public celebrity and its necessary downhill tumble. Ruddick goes on to defend his intentions, "Whilst there is no denying the tragedy in Chet Baker's life, I felt that Deep In A Dream focused more on Chet's lifestyle, rather than the music he left behind. I wanted to paint a more balanced portrait." Ruddick did exactly that, but not at the sacrifice of the hard story.

Ruddick agreed with the editor, regarding Gavin's book. While admitting that "The book was very well researched, drawing on a large number of original sources...it was ultimately a depressing story, a tale of squandered talent and a harrowing descent into drug addiction." Well, that is exactly what Baker's story was and is and Gavin never claimed to capture anything else but the very public celebrity and its necessary downhill tumble. Ruddick goes on to defend his intentions, "Whilst there is no denying the tragedy in Chet Baker's life, I felt that Deep In A Dream focused more on Chet's lifestyle, rather than the music he left behind. I wanted to paint a more balanced portrait." Ruddick did exactly that, but not at the sacrifice of the hard story. Ruddick goes on to cite three things missing from previous Baker Biographies: first, identification of the "human" element, that Baker was more than his addiction; second, an appreciation for Baker's music; and third, Baker's "stay[ing] true to his principles from a musical perspective, no matter what misfortunes he suffered in his personal life." Gavin never intended to address the music. He left that for the reader to research as he or she saw fit. Jeroen de Valk had just published an excellent working discography that could be used with Hans Henrik Lerfeldt and Thorbjorn Sjogren Lerfeldt's exhaustive Chet: The Discography of Chesney Henry Baker (Jazzmedia, 1991) to further investigate Baker's music. The real bone to pick here is in the first and third items. Once Baker's addiction became full blown that was his focus, not his family, not his music... the addiction. It is the nature of the beast and trying to make it other than that is so much retro-hopefulness, readers and listeners today wanting some indication that there was something else good motivating Baker and his art.

Ruddick's biography is certainly definitive. It is well- plotted and easily read and followed. He is meticulous in following the itinerant Baker across four decades and continents, keeping the story in a chronologic order that can be superimposed over a sprawling discography, thereby giving structure to the structureless. His account of Baker's addiction is more bracing and stark than Gavin's, if anything. For the majority of the story, the middle sections, Baker is submerged in addiction, recording poor or uninspired music, only bobbing to the surface with exceptional musical statement a few times before fully springing up and treading water in the two or three years before his death.

Ruddick captures these highs as well as the lows and puts them fully in perspective, giving the reader and potential listener a roadmap to Baker's often confused late-period discography. While there were many, many bad nights, the good ones do warrant attention. Ruddick keeps his promise addressing Baker's music with a selected annotated discography that fills out de Valk's nicely. Both authors rate the Baker releases using five stars, with Ruddick being much stingier than de Valk, giving them to only one release, Chet Baker In Tokyo (Evidence, 1987). Curiously, de Valk calls this Baker's best release but gives it only 4.5 stars. The two writers fall into order if one equates de Valks 5-star rated releases with Ruddick's 4.5 star discs.

Baker's musical legacy early in his career is fairly well settled with his recordings with Gerry Mulligan and the piano-less quartet, his own Chet Baker Quartet: Featuring Russ Freeman (Pacific Jazz, 1953) and his Barclay recordings with doomed pianist Dick Twardzik noted as historic. Both authors agree on the importance of Baker's drummerless trios of the mid-1980s, with guitarist Philip Catherine on Chet' Choice (Criss Cross, 1985) and pianist Michel Graillier on Candy (Sonet, 1985), and Baker's final performance with the NDR-Big Band and Radio Orchestra Hannover, The Last Great Concert (Enja, 1988).

But I still lacked perspective regarding Baker. I have owned and listened to a pile of his music, often viewing him as a radioactive specter emitting musical waves toxic with the rest of his story. His trumpet playing was often pinched and tentative, and his singing was an acquired taste if there ever was one. But for all of these reservations, Baker's music has always remained compelling to me. Completely untaught and unable to read music, Baker had no business playing anything as well as he did, let alone jazz. But, this same could be said of other jazz autodidacts like Erroll Garner, Stan Getz, and Buddy Rich. In the end, Chet Baker was Chet Baker and no one else. How many artists can boast this?

Ruddick channels musician and writer Mike Zwerin—most notable as trombonist in Miles Davis' nonet on The Birth of the Cool (Capitol Records, 1957). From a 1983 article, Zwerin wrote:

"You do not feel like shouting 'Yeah,' after a Chet Baker solo. All that tenderness, turmoil and pain has driven you too far inside. He reaches that same part of us as the late Beethoven string quartet, a spiritual hole where music becomes religion..."

..."where music becomes religion."

It is in this dimension that Baker's enigmatic playing and singing gains purchase, just as Billie Holiday's did on Lady in Satin (Columbia, 1958) and Last Recordings (MGM, 1959), and Lester Young on Lester Young in Washington D.C., 1956 (OJC. 1956). It is here where Baker joins Mozart where the music transforms from mathematics to the sublime mystic in that composer's Requiem's unfinished Lacrimosa:

Lacrimosa dies ilia

Qua resurget ex favilla

Judicandus homo reus.

Mournful that day

When from the dust shall rise

Guilty man to be judged.

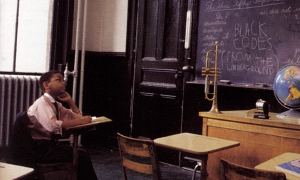

Photo Credits

Page 1: Guy Foncke

Page 2: Michel Verreckt

< Previous

Sweet Happy Life

Comments

Tags

Chet Baker

Opinion

C. Michael Bailey

United States

Art Pepper

Gerry Mulligan

Dick Twardzik

Philip Catherine

Erroll Garner

Stan Getz

Buddy Rich

Mike Zwerin

Billie Holiday

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.