Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Mike LeDonne: Where There’s Smoke

Mike LeDonne: Where There’s Smoke

The moment you want to get to is where all the influences are just kind of flowing, and then it’s you. That’s the thing.

LeDonne is especially happy with his long tenure at the club. "It's an extraordinary thing to have a steady gig like that and then to see people still coming out in droves to listen. And now the word is out all over the world—people know Tuesday night is organ night at Smoke. They come to New York just to see it. They come right off the plane from Europe and go right to Smoke." Not only does the club draw crowds of fans, but great elder statesmen of jazz such as Lou Donaldson, Frank Wess and George Coleman often drop by and sometimes sit in with LeDonne. "I'm so proud of that," he says. "If I can attract people like that, I must be doing something right."

Born in Bridgeport, Connecticut in 1956, LeDonne grew up in his parents' music shop; his father, Mickey, was a jazz guitarist who also sang in the style of Nat King Cole. After earning his degree at the New England Conservatory, the keyboardist settled in New York City in the late '70s, and he's been based there ever since.

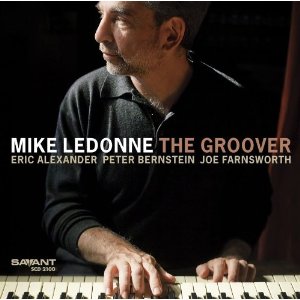

His experience spans an impressively wide range of jazz styles from traditional swing to modern post-bop. Very early in his career, he was a member of the Widespread Depression Orchestra, playing classic charts of the swing era, and before long, he was playing with Benny Goodman. In the early '80s, he was the house pianist at Jimmy Ryan's, a mainstay of New York's traditional jazz scene at the time, and he went on to work with the Art Farmer-Clifford Jordan Quintet in addition to playing with Dizzy Gillespie, Stanley Turrentine and Sonny Rollins, among many others. His 11-year stint with Milt Jackson is especially notable—LeDonne ultimately served as the musical director of the vibraphonist's working band—as is his long association with Benny Golson. He appears on the saxophonist's New Time, New 'Tet (Concord, 2009) album and three other Golson CDs. Under his own name, LeDonne has recorded 14 albums with featured personnel including Ron Carter, Joshua Redman and Lewis Nash, in addition to his colleagues at Smoke, together known as The Groover Quartet, comprising Eric Alexander, Peter Bernstein, and Joe Farnsworth.

All About Jazz: Your 12-year organ gig at Smoke must set some kind of record.

Mike LeDonne: Smoke is my home in New York. I love Smoke. That's where you hear guys still going for it and playing real jazz music all the time. They allow swing. They allow the blues. They love all of it there, and you can't find that kind of variety in a lot of places these days. Everybody's trying to move the music forward, and so we're getting away from what are the true, deep roots of the music—the blues and the African-American tradition—which, to me, is a sin. I always say it's good to go forward, but we need to go up, too. You go forward, and you can fall off a cliff. You need to bring the music up and stay true to its roots. That is huge in my mind, in my heart and in what I play. I'm going for that feeling at the heart of the music, because I know that feeling from playing with the guys I've played with and from listening to the music all my life. That's what got me into it—the feeling. I didn't know what they were doing. I didn't know what Wynton Kelly was playing. But I knew that feeling was giving me something that I wanted to be able to give someone else.

Smoke is a place where I've been able to develop my organ style for 12 years now. You know, I've been playing organ since I was 14—10, really, but I got a Hammond B3 when I was 14. My father owned a music store. So I've been playing it all this time, but I always kept it in the background. I really didn't want to change my vibe with it by getting out and being all serious with it. I didn't want to get in the arena and be in competition with the other guys out there, but when I played at Smoke, they just threw me in the ring. It was supposed to be a four-week engagement, and it turned into 12 years.

And I don't just do the Tuesday-night organ gig—I do weekends there, too, sometimes, and get involved in the other music they present there. It's all real jazz, and it's the kind of jazz where people walk in and say, "I didn't know this was jazz." They're surprised because it feels so good. They might have been to one of the other big-name clubs around town and felt like they were in church on Sunday. At Smoke, you can really have fun. And you can talk, too. Sometimes it might be a little too much for my taste, but I don't want to take that away. I like people to enjoy themselves. That's what jazz was. I'm sure when Charlie Parker was playing, they didn't go around shushing people. People were quiet because he was just playing so much stuff.

AAJ: Can you tell us a little bit about the guys in the band: Eric Alexander, Peter Bernstein and Joe Farnsworth?

ML: Peter, Joe and Eric and I were playing together long before Smoke. They're all about 10 years younger than me. I met them when I was playing around already, and they were just kids going to school, really. Then we started playing together—it must be 20 years ago. And we're great pals. We've been through all this stuff together, been all over the world together. We've had our kids during the Smoke gig. We've grown old together. It's like an old married couple, kind of. We fight, and we make up and all that kind of stuff. But Peter is my favorite guitarist, and Joe's my favorite drummer, and Eric is my favorite saxophonist. And that's not to put anyone else down. That's just me. So, it was very lucky for me to have my favorite guys in my group and with me all the time.

AAJ: Does Eric Alexander's experience with Charles Earland mean a lot, working in the organ context?

ML: Of course, because not only did that make him know what to do, but it's so nice to have someone who loves that kind of music. You have to have that. I've had a lot of people ask me to do the gig—and they're great players—but I can tell when they don't really love this kind of stuff. It's not really their favorite thing, but they want a gig, and they want to make the money, and that's cool, too. But it's so much better when somebody's really in love with this kind of thing and just knows what to do. Eric can do anything, but what I love about him is not only is he modern—with his own conception and his own harmonic devices and all—but he also has a lot of Stanley Turrentine, Gene Ammons, Dexter Gordon in him. And, of course, George Coleman is a huge influence on him, and George is so soulful. He comes up there all the time. Not only is he an innovator, but he's so soulful and great. He's my buddy. And Lou Donaldson comes up all the time. Frank Wess was in there last night. And so it's become like a scene. . . . I mean, if I can attract people like that, something's got to be going right. You can criticize it—it's not perfect, you know. But, hey, if those guys like it, it's got to be pretty good.

AAJ: Where else have you been playing lately outside of New York?

ML: Well, I've done the Detroit Jazz Festival a couple of years in a row, the Chicago Jazz Festival, some other festivals in the Midwest—a lot of the jazz festivals all around. It's all part of what I do—and I've been doing it for 35 years, now. I go to Europe regularly—Italy and Germany. I have a trip to Germany in September, just going to go there by myself this time. That's a new thing; usually I bring my own group, but there are some musicians based there who want me to come and play with them, so I'll go try it.

AAJ: You have some recent recordings out—Keep the Faith (Savant, 2011), and there's a great new record you're on with Eric Alexander and Vincent Herring as co-leaders, Friendly Fire (High Note, 2012). On Keep the Faith, you have a number of original compositions.

ML: Well, it's all stuff that I come up with at Smoke. I have that luxury of trying things out there. I write every day. I love writing as much I do playing, really. So I write stuff every day, and a lot of it just goes in the delete box. But I'll get something that I think is pretty cool, and I'll bring it in and try it, and then it still may go in the delete box if people don't like it. The tunes on the record are tried and true, what I call "hits."

The tune "Keep the Faith" itself is by Charlie Earland. I wrote a tune for Big John Patton on there, called "Big John," which is sort of in memory of him and his style. I wrote a tune for my daughter, Mary, on there, called "Waiting for You," which is what we're always doing, waiting for her to do something. "Scratching" is an old one. I recorded that on Criss Cross a long time ago. Harold Mabern's been hearing it for years, and he just realized it's written over "Just in Time" changes about two weeks ago. Peter Bernstein quoted "Just in Time" in it, and he said, "Hey, all this time I've been listening to it, I didn't realize it was 'Just in Time.'"

"Burner's Idea" is for Charlie Earland. It's a little lick that I heard him play once, and I just made a tune out of it. And that's what I do. I just try and come up with something that fits the group and is not too hard, because we never rehearse. We have never rehearsed. We play every week, but still, you bring in something to read on the gig and it's a packed house—you can't stop and describe how there's a hit on the and of four here, or you have to watch for a key change there, or whatever. It's got to all just lay out and play itself, be that kind of tune. In a way, it's limiting what I can do, but it's been a good limitation because it's made me think simpler and come up with stuff that actually sounds like songs and stuff that is still interesting and challenging to play.

AAJ: The Groover is another outstanding recent recording—kind of similar to Keep the Faith.

AAJ: The Groover is another outstanding recent recording—kind of similar to Keep the Faith. ML: I would say Keep the Faith is part two of The Groover. The Groover was such a hit. It was like a number-one hit for months—tons of airplay on jazz radio. And I got lots of gigs off of it; I got festivals, all kinds of people calling me from it. It was really an explosive thing. So I thought, "OK, well, people like it—do it again." And then I did Keep the Faith, and I got nominated as top keyboardist for 2012 by the Jazz Journalists Association, and I won the DownBeat critic's poll as "rising star" on organ. I guess I'm an old star but not a falling star. I'd rather be rising. But, hey, I'll take whatever I can get. It doesn't really mean a whole lot to me, really, because it seems so strange to see Melvin Rhine's name at the bottom of the "rising star" poll, for example. Nonetheless, it's recognition; that's all it is—somebody saying, "We like what you're doing." And that's not bad. I never used to get these kinds of accolades. I've never been the guy in the polls at all. But lately, people are writing articles—DownBeat recently, for one. This is all new ground for me. I've always been the underground guy who everybody likes but the general public doesn't know that well. Not a household name.

Another new album I did is called Up a Step (Cellar Live, 2012), recorded at a club I play in Vancouver, called The Cellar. The gentleman who owns it is a very good tenor saxophonist named Cory Weeds. It's his record. We did a live record with him and Oliver Gannon, Jesse Cahill—Canadian musicians. We also did a little tour. And I'm going to be going up there again to make a live piano trio record in December. And I'll probably do another organ record for Joe Fields, on Savant in the fall.

The trio record will be with Joe Farnsworth and John Webber. It's great because I've never been able to record with them as a trio, and that's been my working trio for years. So I've finally got someone to record us. I've always had to have a big name involved for my other trio records—my last one had Ron Carter on it. It's not that I'm against that—I'd just love to do one with my working trio, so, I'm just doing it.

AAJ: Another gig you've done in recent years in New York that not many people know about is playing solo piano in Bryant Park mid-day for a week in the summer. Harold Mabern paid you a visit this year one day, right?

ML: Harold Mabern is awesome. He's my great friend. We talk on the phone all the time, and he's super supportive. Not only is he a monster musician, but he's a beautiful human being. And it's just a joy to be around this guy. He got up and introduced me to the crowd. I finished my set and just waved goodbye. And he stopped me, and he got up and said, "Wait a minute, Mike. I'm going to say, because you're too humble to say it, this is Mike LeDonne!" And he just went off and gave this whole rap about me and told them I played at Smoke and other stuff. That's Harold Mabern, man. He's a beautiful guy. But, see, he can give it up to people because he's so great. When you're great, you can give it up, and say, "Well, you're great. I love your playing." And that's when it really means something.

AAJ: Does playing that gig in Bryant Park give you any ideas about recording a solo piano album?

ML: It does make me think about it. I'd feel a lot better about doing it now than I ever did before. I used to play set arrangements for my solo piano gigs, and then I just felt like it trapped me. I was playing those same tunes the same way. And then I just thought, "To hell with all that." I was just sitting here on that funny little piano in the park, and I was thinking, "Why do all that? Just play!" Also, I think, in my own playing, I've always been trying to open it up. I don't want to get boxed into any one thing. That's called growth, and that's what I want to do for the rest of my life. I push for that. I focus on that. I'm not looking to reinvent the wheel but just to get better and find myself more and feel more comfortable in what I'm doing, more secure and solid. All these things—I feel like it's happening. I can feel it.

I can feel the difference from when I used to play my solo piano gigs years ago. My favorite guy was Hank Jones, and I knew all his arrangements. I used to try and play just like Hank Jones, and it was a great learning experience. But then I thought, "How long can you just sit there and play like Hank Jones?" And then I went through a phase where loved Cedar Walton, and I knew his solo piano material. I'd play all his repertoire because I just loved it. It was fun to try and do, and I just didn't feel secure enough about myself yet—about me just playing me. I think that's typical for a lot of musicians. Then I got into McCoy Tyner and Phineas Newborn, Jr., and those guys really opened me up. At one point, I was almost starting to think my little McCoyisms were taking over.

I can feel the difference from when I used to play my solo piano gigs years ago. My favorite guy was Hank Jones, and I knew all his arrangements. I used to try and play just like Hank Jones, and it was a great learning experience. But then I thought, "How long can you just sit there and play like Hank Jones?" And then I went through a phase where loved Cedar Walton, and I knew his solo piano material. I'd play all his repertoire because I just loved it. It was fun to try and do, and I just didn't feel secure enough about myself yet—about me just playing me. I think that's typical for a lot of musicians. Then I got into McCoy Tyner and Phineas Newborn, Jr., and those guys really opened me up. At one point, I was almost starting to think my little McCoyisms were taking over. I get to this point where I'm really into somebody—I was into Wynton Kelly first. It would be like three years of just him. I mean, I listened to other people. I always listened to Herbie Hancock and all of the guys who are great—Bill Evans and whoever. But Wynton was the one who really lit my fire. So it was three years of finding every record that he was on, listening to every solo that he did, just trying to sound like him—I couldn't, but if I could, I would've sounded just like him because I just loved him so much. And that's basically my style. I get one guy I latch on to and just go for it, for years, until I really get into the depth, into the inside stuff.

AAJ: But your playing has such a personal sound.

ML: I hope so. I'm glad to hear you say that, because you always wonder. I still listen to everybody, and sometimes I feel like one guy might be overshadowing. The moment you want to get to is where all the influences are just kind of flowing, and then it's you. That's the thing.

Now, let's face it, there hasn't really been an innovator, I don't think, since Herbie and McCoy and a couple of others—not a real innovator where after they're here, everyone tries to sound like them. Maybe it'll happen again, and if it does, it'll be out of some natural set of circumstances. It's not going to be through anyone trying to innovate. What I think you do as a jazz musician is you just learn as much as you can about everybody, and you copy the greats, and then, the way you put it together, that's you.

AAJ: You didn't mention Oscar Peterson.

ML: He was an innovator, because so many guys tried to sound like him—grew out of him, like Monty Alexander and guys who I hear all the time that try and sound like Oscar. There's a whole Oscar cult. But I never particularly tried to sound like him. Oscar goes way back, and he's a top master. He had his own thing completely. He really came more out of Nat Cole than Art Tatum. Everybody mentions the Tatum thing, but he really was a Nat Cole guy. And Nat Cole was another guy who was an innovator that nobody talks about. Earl Hines was another top innovator. There's a similarity between Earl Hines and McCoy with how free they are. Earl Hines was the first McCoy, to me. He's that free in his thinking. He had no limits, no boundaries whatsoever. He'd just be exploding, and it was all just coming out all the time. He's the first pianist I ever heard like that. Art Tatum was influenced by him. You've got to be pretty mean to influence Art Tatum. And Erroll Garner was influenced by him. Everybody—Nat Cole, too. Then you've got Bud Powell; he changed everything. And he's obviously an innovator.

But I say there are innovators, and then there are language changers—two different things. A lot of guys innovate certain things. Bill Evans innovated some things, but basically, when you get down to it, he was a bebop pianist. Herbie innovated a lot of things, but to me—maybe not today, but when he was with Miles, at the time he made his huge impact—even though he was expanding the harmony and rhythms of it, he was still playing bebop, basically, playing that language.

But when McCoy Tyner came up with his thing, and you hear "Passion Dance," and you hear the language—totally different. Nothing like it ever existed before. And that's a language changer. And then, after that, Herbie was influenced by him, Chick Corea, Keith Jarrett —everybody had to be influenced by him because he changed everything. There's not many of real language changers, when you look at the history. There's just a handful. There are guys who come up with stuff of their own that people try to imitate, and that's innovation, too. There are all kinds of innovation, but I'm always most impressed by the guys who change the language. Where do they come from? They change everything. How does that happen? I have no idea. I think it's a whole set of circumstances. With McCoy, he was with 'Trane. It was a special time, that era, and, boom, it happened.

But when McCoy Tyner came up with his thing, and you hear "Passion Dance," and you hear the language—totally different. Nothing like it ever existed before. And that's a language changer. And then, after that, Herbie was influenced by him, Chick Corea, Keith Jarrett —everybody had to be influenced by him because he changed everything. There's not many of real language changers, when you look at the history. There's just a handful. There are guys who come up with stuff of their own that people try to imitate, and that's innovation, too. There are all kinds of innovation, but I'm always most impressed by the guys who change the language. Where do they come from? They change everything. How does that happen? I have no idea. I think it's a whole set of circumstances. With McCoy, he was with 'Trane. It was a special time, that era, and, boom, it happened. AAJ: Is this something that you strive for at all yourself—to change the language?

ML: Everyone thinks about it. But I don't really strive for it. If it happened someday, I would be floored. In fact, though, I don't think you even know it when you're doing it. I knew a guy who played with Bird. He used to play with me on 54th Street when I played at Jimmy Ryan's. His name was Ted Sturgis, a bassist. He played with Charlie Parker in his very first group on 52nd Street with Dizzy—with Bird and Diz. He's the guy that Bird wrote the tune "Mohawk" for. Ted is Mohawk because he had Indian blood in him. He used to tell me how, when Bird and Diz and he were playing, they'd read all this news in the music publications, like, "These guys are changing everything. The bebop language is all new. It's never going to be the same." Bird and Diz were, like, "What? Who are they? Because we're just playing." They didn't try to do anything new. They just played, and it happened, and they were just playing their stuff. And then, suddenly, it was like everyone was saying, "Oh, my God! The messiah has come!" But they didn't think about it that way at all. Now John Coltrane, he really was searching, but I think he was just practicing and getting better and getting ideas. That's how it happens. You can't set out and say, "Yes, it's very important to change the language. I'm going to do it." You can't do that. And you don't have to. But if you get better and better, who knows? It might happen.

AAJ: Can you tell us a little about your work with Benny Golson, Milt Jackson, and the other masters you played with, coming up?

AAJ: Can you tell us a little about your work with Benny Golson, Milt Jackson, and the other masters you played with, coming up? ML: I had been a sideman for many, many years. I was so lucky in those early years. When I came here to New York in the late '70s, there were so many masters still around, and I got to work with a lot of them. The Art Farmer-Clifford Jordan Quintet, Sonny Rollins, even Benny Goodman, way back, when I was about 25. I worked with a lot of traditional jazz guys like Ruby Braff and Vic Dickenson, and then I moved on to Milt Jackson, Art Farmer, and played with Bobby Hutcherson.

So I've done a wide spectrum of playing, and I'm probably one of very few in my age group who's covered such a wide of a spectrum of styles. I knew about all the swing stuff and Benny Goodman from my experience with the Widespread Depression Orchestra. It was a perfect school for all that—I learned all the tunes. I knew how Teddy Wilson played, Earl Hines and Hank Jones. I knew how to bridge the gap between bebop and swing so that I could play me with him and not tick Benny off. The swing guys then didn't like Bird, really. They didn't like Bud Powell. If you sat down and played like Bud Powell, you'd be done. The job would be over. So I had to lean different ways, and that's what you learn as a sideman—how to lean into this and lean into that to make the leader happy and do the right thing for the gig, because it's not about you, it's about him—if you want to keep the gig.

When I came here, no one my age had a record deal, except for Scott Hamilton, the tenor player. I recorded with him, and I played with him quite a bit. He was my buddy, and he played a little more traditional than I would have liked to have been playing at the time, but I knew how to lean into his thing, too. That's how I kept that gig. Ruby Braff was good friends with Scott and Warren Vache—I played with all those guys from what I call the "trad" scene. All through that, though, I was always into a wider variety of stuff than they were, although Warren is very open minded.

Back in those days, I'd be going to these gigs with these guys but listening to Miles Davis' In Person at the Blackhawk (Columbia, 1961)—one of my favorite records, with Wynton Kelly, Jimmy Cobb, and Paul Chambers. I'd just be dreaming, thinking "Oh man, I wish I was doing this tonight, but OK, whatever. I'll do this gig."

Fast forward to May, 2012, and Smoke has a Miles Davis tribute, and there I am playing with Jimmy Cobb and not Paul Chambers but John Webber, who sounds very much like him, and Eric Alexander, Jeremy Pelt and Vincent Herring, and we're doing all the stuff from the Blackhawk, from Someday My Prince Will Come (Columbia, 1961) and Kind of Blue (Columbia, 1959). And there I was, doing it. All that dreaming and wishing, and my dream came totally true. It felt just the same, and I was just beaming the entire time—one of those gigs where all day long, I couldn't wait to get back and do it again. We did four nights. It was just—every night, every set was just incredible. Jimmy Cobb sounds just as great as he ever did. He's 83. And he has it all. He has the whole package, still: soloing, swinging, accompanying. Comping with him is just a joy, because I know Wynton Kelly inside and out. And that was his man. I've played with Jimmy before, many times. But that was special for me. That was a very special thing. So it just goes to show sometimes dreams can come true.

Playing with Milt Jackson was another dream come true, because I used to go see him all the time. He was a genius. Nobody could play vibes like him before or since. And his was my favorite group: Ray Brown, Billy Higgins, Cedar Walton and Milt Jackson.

Good lord, man, those guys were so great. There wouldn't ever be a moment where you were looking at your watch and thinking about what you had to do tomorrow. You were just beaming ear to ear listening to that music, and you couldn't wait for the break to be over, you wanted another and more—give me more! When they played the Village Vanguard, I went every night—not one night, every night. I couldn't resist.

When he called me to play the gig, he didn't really know who I was. James Williams gave him my name; he was my buddy, and I miss him. Cedar was the regular pianist in the group, and James Williams would sub for him. But a gig came up that neither Cedar or James could make, and James gave Milt Jackson my name because he knew how much I loved Bags [Jackson's nickname]. Bob Cranshaw, who was playing bass with him by then, knew me, too. Bags asked him who this guy Mike LeDonne was, and Bob said, "You know that guy. He's always sitting in the corner seat in the Vanguard when we play there, every night. The guy with the beard!" So, when I went to play with Bags the first time in Philadelphia, I knew all the tunes. I just sat right in and knew what to do. But at the time, I thought I did terribly. Cedar was my biggest influence then. I didn't want to hear anybody but Cedar. And here I was, trying to fill Cedar's shoes. I was so scared. I got through the gig, but I didn't know what to think. You know, Bags is a quiet guy. He's not a very demonstrative guy, and I was so in awe of him I could hardly talk to him. So, the gig came to the close at the end of the night, and I was actually walking over to him to shake his hand and apologize. And I was in the middle of saying, "I'm sorry," and he grabbed me and gave me a big hug and said, "I got you now! Beautiful!" And that was it. I stayed with him for 11 years.

Eventually, Cedar stopped doing it, and James got very busy, so I started subbing more and more, and eventually I wound up on that gig and being musical director—picking all the tunes, writing arrangements. He was doing my tunes! And we became like family. I'd call him up and talk about anything, go hang with him out at his house. He was truly my buddy. We'd go on the road together. He'd bring pies. He was a baker; he used to bake pies—sweet potato pie or pineapple pie, which I never had before, and other kinds, too. We'd be going to Japan, and we'd have three or four pies circulating in business class, giving everybody a piece—stewardesses, too. That's what it was like with Bags. It was just a party. He never said one word to me like, "I don't like the way you're doing this," or "I don't like the way you're doing that." Never. Just do your thing, and do it to the fullest.

Eventually, Cedar stopped doing it, and James got very busy, so I started subbing more and more, and eventually I wound up on that gig and being musical director—picking all the tunes, writing arrangements. He was doing my tunes! And we became like family. I'd call him up and talk about anything, go hang with him out at his house. He was truly my buddy. We'd go on the road together. He'd bring pies. He was a baker; he used to bake pies—sweet potato pie or pineapple pie, which I never had before, and other kinds, too. We'd be going to Japan, and we'd have three or four pies circulating in business class, giving everybody a piece—stewardesses, too. That's what it was like with Bags. It was just a party. He never said one word to me like, "I don't like the way you're doing this," or "I don't like the way you're doing that." Never. Just do your thing, and do it to the fullest. It was the same with Benny Golson. He never said one thing to me. He's the one who really allowed me to expand my voice, because he wanted that. He wanted you to push, to go to the next level. He was so encouraging to me. I have all these letters from him that he's sent me. He'll send me a present in the mail out of nowhere. He wrote a tune for my daughter. It's called "Little Mary," and it's on my Groover record. He sent it to me one day just out of the blue. I got a FedEx. I had no idea what it was. I pulled it out—here's an original Benny Golson composition written for my daughter, and it's great. And I played through it, and I said, "Oh, my God! I've got to record this right away." What an honor, man—the guy who wrote "I Remember Clifford" and "Whisper Not." He wrote "Little Mary," and now it's in his book. And so my daughter has that for the rest of her life. It's like Duke Ellington writing a song for your daughter. He's a very supportive guy, and he really loves it when you move on to something else. And there's no pressure for it, but he's listening like a hawk.

AAJ: Getting back to the organ, in your discography you made a record with Michael Hashim in 1991 along with Peter Bernstein, Blue Streak (Stash). It was kind of a forerunner of your organ work.

AAJ: Getting back to the organ, in your discography you made a record with Michael Hashim in 1991 along with Peter Bernstein, Blue Streak (Stash). It was kind of a forerunner of your organ work. ML: It was. It might have been my first organ record. Peter was on that and Kenny Washington on drums. Mike and I were together in my very first group that came to New York, the Widespread Depression Orchestra. We did all that Count Basie and Earl Hines material, and it was a great education to be in that group. Mike was sort of the spokesman for the group, and I knew him in Boston, too. We met when I was in school way back there in the '70s. He was going to Berklee, and I was going to New England Conservatory. So we go way, way back. He knew that I played organ. He used to come to my house sometimes when I went home to see my family, and we'd play together with me on organ. So it was natural when he wanted to do an organ record to have me do it, because he knew I could play. Whereas, my record company at that time didn't want me to do an organ record. They were afraid I was going to confuse people, and maybe they were right. I don't know, but if I had, it might have been a whole 'nother thing, because I would've hit the scene before Joey DeFrancesco or before Larry Goldings. I love both those guys. They're exceptional players, but I'm older than both of them by about a good ten years. I might've been the first guy doing it. That might have been—who knows—something for me. But at that time, my record company was just trying to put me over as a pianist. I was mainly playing the piano, known on the piano and getting gigs on piano.

The first guy who heard me play organ and really gave me a professional gig was Percy France, who was a tenor player who used to play with Bill Doggett and Jimmy Smith—great tenor player, local Harlem guy who heard me play and brought me in to play with him every Wednesday at Showman's, which is in Harlem, with Joe Dukes, who is one of the great organ drummers of all time. We did that for three years, every Wednesday, and that's where I really cut my teeth, learning and trying to get it together. He was so sweet to me, always. That was the early '80s. And that's when I bought another organ. It was after I sat in at a gig Jack McDuff was playing in Harlem, and a friend of mine, Jim Snidero was in his band. Jim told me to come up there and play the organ—to sit in on Jack's gig. I said, "Are you crazy? Jack McDuff's one of the greatest in the world. I'm not going to go." He said, "Come on. Just give it a shot. It'll be fun. Jack's not going to care." So I went, and Joe Dukes was playing drums then. It was like a kind of a sextet with some horns and stuff, and Dave Stryker was playing guitar. I sat in, and I played one tune. And then Jack came over to me and said, "Man, you know what? You sound good on organ. You should be an organ player." And I said, "Wow, man, yeah!" So I went and bought an organ, almost the next day. I called my folks. I said, "OK. I need your help." I found one for two grand. They paid for it, and I put it in my apartment here, and the rest is history. I just kept going with it. Otherwise, who knows? I might've never done it.

At Smoke, I lent them my organ for the first year, because they weren't sure about how it was going to go over, and then they finally bought one. And it's been going for 12 years. It still gets packed. . . . A steady organ gig for 12 years in this day and age? I think if we look back at it later on, it's going to be seen as a piece of New York history. It's like the Vanguard Orchestra at the Village Vanguard. I'm not saying that we're making history, but just doing that gig is a piece of New York history.

strong>AAJ: You've talked about guys who have influenced you, and you've influenced a lot of people yourself on a professional level and through teaching.

strong>AAJ: You've talked about guys who have influenced you, and you've influenced a lot of people yourself on a professional level and through teaching. ML: I was at Juilliard for four years, and for about the last 15 years or so I've been teaching at an all-day Saturday program for high-school students at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center in Newark. Teaching can be a lot of work. It's not something I want to be a major focus in my life, but doing NJPAC and working with a few private students is nice for me. I love NJPAC because it's teenagers. It's hard on the college level because then it's already kind of late in the game. The kids at the high-school level are much sweeter. They'll do what you say, especially when they hear you play and they hear your name on the radio. They're, like, "Hey, maybe we should pay attention to this guy." I've had so many great experiences there. They can be difficult sometimes, but also you're getting them from square one. They're coming in as a blank slate. You can really take them and mold them. I'm able to shape their styles, to teach them what I wish somebody taught me at their age. That's why I do it. Sometimes, it's true, they think they know everything already, but I don't play any games with these kids. And, inevitably, within a year or two—I've seen it over and over—they come back after the summer and all of a sudden, bam! They're doing it. They know the language. They're playing, and then they're on the road. I see they're heading off to music school, and I say to myself, "I had something to do with that." And they're all out here now. David Zaks, Alex Collins, Brandon Wright, Benny Reid, these are all guys that are out in the scene actively playing. Evan Sherman—a drummer in the ensemble I teach—he's going to Juilliard, and he's playing great.

< Previous

Plunge

Comments

About Mike LeDonne

Instrument: Organ, Hammond B3

Related Articles | Concerts | Albums | Photos | Similar ToTags

Mike LeDonne

Interview

Bob Kenselaar

United States

New York

New York City

oscar peterson

Lou Donaldson

Frank Wess

George Coleman

Nat King Cole

Widespread Depression Orchestra

Benny Goodman

Art Farmer

Clifford Jordan

Dizzy Gillespie

Stanley Turrentine

Sonny Rollins

Milt Jackson

benny golson

Ron Carter

Joshua Redman

Lewis Nash

Eric Alexander

Peter Bernstein

Joe Farnsworth

Wynton Kelly

Charlie Parker

Charles Earland

Gene Ammons

Dexter Gordon

John Patton

Harold Mabern

Cory Weeds

Oliver Gannon

Jesse Cahill

John Webber

Hank Jones

Cedar Walton

McCoy Tyner

Phineas Newborn

Herbie Hancock

Bill Evans

Monty Alexander

Art Tatum

Earl Hines

Errol Garner

Bud Powell

Chick Corea

Keith Jarrett

John Coltrane

Ruby Braff

Vic Dickenson

Bobby Hutcherson

Teddy Wilson

Scott Hamilton

Warren Vache

Miles Davis

Jimmy Cobb

Paul Chambers

Jeremy Pelt

Ray Brown

Billy Higgins

James Williams

Bob Cranshaw

duke ellington

Michael Hashim

Kenny Washington

Count Basie

Joey DeFrancesco

Larry Goldings

Percy France

Bill Doggett

Jimmy Smith

Joe Dukes

Jack McDuff

Jim Snidero

Dave Stryker

Alex Collins

Brandon Wright

Benny Reid

Evan Sherman

Jaki Byard

Michael Weiss

Tom Harrell

Gary Smulyan

rudy van gelder

[Thelonious] Monk

Tommy [Flanagan]

Barry Harris

Concerts

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.