Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Maxine Gordon: The Legacy of Dexter Gordon

Maxine Gordon: The Legacy of Dexter Gordon

Gordon's wife and longtime manager, Maxine Gordon, has kept the legacy strong through lectures and guest appearances, donation of all of Gordon's archival work to the Library of Congress, the licensing group Dex Music LLC and The Dexter Gordon Foundation. She is currently writing his biography, due for release in 2013. She often works closely with her son, Woody Louis Armstrong Shaw III, who is administrator, general manager, and web publisher for Gordon's legacy. Woody III was curator, co-producer and project director for two recent box sets covering the mid-to-late 1970s recordings by Dexter Gordon (his stepfather) and the great trumpeter Woody Shaw (his father), both called The Complete Columbia Albums Collection and both released by Columbia/Legacy in 2011.

In addition to her tireless efforts on behalf of the Dexter Gordon legacy, Maxine Gordon is a scholar, researcher, and archivist who has done pioneering research on jazz in Harlem in the 1930s and the history of jazz in the Bronx, NY. She is also compiling information for a book on three great women of jazz: trombonist Melba Liston, organist Shirley Scott, and singer Maxine Sullivan. An avid jazz fan for decades, Maxine Gordon is a force in her own right, advocating for the music and the musicians in many capacities, as partner, friend, manager, and scholar. Her presence at and recollections of many events in Dexter Gordon's career and in jazz history provided rich material for an interview, and her own career and scholarly work provided additional incentive and inspiration.

Chapter Index

Dexter Gordon's Famous Homecoming

The Dexter Gordon Legacy Today

Recalling Dexter Gordon and His Cohorts

Making the Film Round Midnight

Maxine Gordon: Entrepreneur, Scholar, Writer

Researching the Jazz Scene in Harlem and the Bronx

The Special Relationship between Musicians and Their Fans

Dexter Gordon's Famous Homecoming

AAJ: You had close contact with Dexter Gordon for a couple of decades. What has been the nature of your relationship with him? How and when did you meet him?

MG: I first met Dexter in 1975 in Nancy, France. I was working as a tour manager, which at that time was called "road manager." My job, among other things, was to help the groups move around Europe. Dexter was living and performing in Europe at the time. He had Tony Inazalaco on drums, Jimmy Woode on bass, and a pianist whose name I don't recall, and they all traveled by train at that time. It so happened there was a train strike, and I had the daunting task of moving them around through Italy, France, Denmark, and everywhere. I was under a lot of pressure to get them to the next gig. So I had to go to talk with Dexter about all that.

Prior to that, I had only seen him once before at the Jazz Gallery in New York in the 1960s. I was an avid jazz fan even then, but I didn't know Dexter well, because I came in with Art Blakey, John Coltrane, and so on. But when I went to see Dexter at his gig in Nancy, we immediately struck up a friendship and started traveling together as well.

I remember at one point saying to him, "You should come back to New York. You sound great. People there should know how good you are. There's a big hole there because Trane is gone, and you can help fill it."

AAJ: That's a piece of jazz history—you were the one who encouraged him to return to New York.

MG: He said, "I want to come back. But I don't know how to arrange it." And we started a conversation about him coming back to the States. I didn't know much about the management end, but I had helped [organist] Shirley Scott with some bookings. And I had done some similar things for Harold Vick. I wanted to help him, but wasn't sure what I could do. When we got to Holland, we decided to work together for six months and see how it went. Dexter had some money saved and gave me an advance for my expenses.

MG: He said, "I want to come back. But I don't know how to arrange it." And we started a conversation about him coming back to the States. I didn't know much about the management end, but I had helped [organist] Shirley Scott with some bookings. And I had done some similar things for Harold Vick. I wanted to help him, but wasn't sure what I could do. When we got to Holland, we decided to work together for six months and see how it went. Dexter had some money saved and gave me an advance for my expenses.So we formed a loose partnership based on the idea of getting Dexter back to New York. But I had also been traveling with a great band with Woody Shaw, Louis Hayes, Junior Cook, Ronnie Matthews, and Stafford James. I was the sixth person with that group on the train—six of us could fit in a train compartment, the quintet and me. When I told them Dexter wanted to come back to New York, Woody was excited. He said, "Great! Fabulous! We need him there!" They'd played together in George Gruntz's big band. So Woody was the one who talked it up with the musicians about Dexter's coming back, how he was modern but very bebop, and so on.

So, when I got back to Holland, the first thing I did was to call Max Gordon [owner of the Village Vanguard in New York] I'd been going to the Vanguard since I was 16, and Max had become a friend. He would look out for all the bands, but he kind of pitied us young fans who had no money, and he'd have us sit in the back by the bar—and that was me. So I called him and said excitedly, "Max, I heard Dexter Gordon, and he sounds so great, and he wants to come back to New York. Why don't you give him a gig?" Disappointingly, he said, "No, I can't give him a gig. Everyone here forgot him. He's been away too long." So I said, "Max! You have to book him. If you don't, I'll never speak to you again!" And he said, "So what, I don't care!" And he hung up on me! But the next day, I called him back, and said "Max! Let's talk about this!" And he said, "OK! I'll give him a gig, but no guarantees. If he makes money, I'll give him money. If he doesn't, you'll have to pay the band yourself."

I then told Dexter, "Max's deal is a tough one, but if you play in the Vanguard, if we promote it and people come, you'll sound great and people will love it. So would you invest your own money and take the risk?" He said, without hesitation, "Yeah! Let's do that! How much do we need?" So he put aside the money, and we also booked a couple of gigs outside of New York prior to the Vanguard. And then he also got an opportunity to open at Storyville in Manhattan, George Wein's little club on the East Side. Wein gave Dexter a bit of a showcase there. In Stanley Crouch's depiction of Dexter's return, he describes how he appeared out of nowhere, and it's snowing, and there are lines of people around the corner, and he gets a contract with Columbia Records. That was the place, but of course it wasn't all that dramatic.

AAJ: Wasn't it Bruce Lundvall who came down there and offered him the Columbia gig?

MG: Yes. I knew Bruce already by then. Michael Cuscuna was Woody Shaw's producer, and he came down there when Dexter was rehearsing, they talked, and it was decided that Michael would be the producer of Dexter's recordings as well. Then Bruce came in, and said right away, "I want to sign him to Columbia." And I became the executive producer.

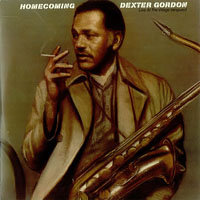

Dexter did great at Storyville and got fabulous reviews. By the time we got to do the Vanguard, we had already set up a live recording with Columbia, namely Homecoming (Columbia, 1977). But the band that he first used wasn't exactly what we wanted, so Woody stepped in and said, "OK. I'll play with Dexter, and I'll get Ronnie Matthews, Louis Hayes and Stafford James to do it." And they did the Vanguard together. And then Woody also got a contract with Columbia.

Shortly thereafter, Michael Cuscuna and I opened an office at 38 West 53rd Street, in a brownstone, which has since been torn down for shops, across from the Museum of Modern Art and right next to Columbia Records. We were over at Columbia's office every day, because we couldn't afford long distance and had to use theirs. So we had daily contact with Bruce Lundvall, who was excited about Dexter's return and so helpful to the project.

We were also very lucky to have Hattie Gossett working with us. She ran the office and kept everything moving and did the publicity and all those phone calls. This was before internet. We used a teletype machine in those days.

AAJ: What a terrific story, and it fills in some gaps in Dexter's homecoming, a famous episode in jazz history.

The Dexter Gordon Legacy Today

AAJ: Coming back to the present time, I'm struck that there's a lot of action happening now around Dexter and his music and life. There's your preparation of his biography, for one thing. Then, your son Woody Shaw III, recently released the boxed sets of the Columbia recordings. In 2010, you donated Dexter's archives to the Library of Congress. Why is all this happening now, over 20 years since his death?

MG: We also have reproduced Dexter's actual mouthpiece for sale by RS Berkeley's Legend Series, both tenor and soprano versions, which is noted on Dexter's website. And this year in 2012, we're initiating The Dexter Gordon Foundation, on behalf of which we have already donated money to the Jazz at Lincoln Center Essential Ellington program, which fosters school big bands. The bands come to New York to compete with each other. We sponsored a band that came from an economically challenged area in East St. Louis. We gave our donation in the name of Samuel A. Browne, who was Dexter's band director at Jefferson High School in Los Angeles. Dexter felt he owed a great deal to Mr. Browne, who taught him to read music and play in a band. Dexter left high school in order to join Lionel Hampton, but he always credited Sam Browne, who also taught Hampton Hawes, Chico Hamilton, Eric Dolphy, and Melba Liston—quite a list of students. So we donated money in Mr. Browne's name to help the students come to the competition.

In addition to the Foundation, we also have Dex Music LLC which handles the licensing, publishing, and so on, and which I've turned over to my son Woody Shaw III. I've had to direct my attention to Dexter's biography, and I've had to develop skills necessary for that project. I had to start documenting all the many facts, you know, that Dexter was born in L.A. in 1923; his father was one of the first African American physicians; his grandfather was a medal of honor recipient in the Spanish American War, and so on. But I didn't want to just collect facts randomly, so I went back to school to develop my research and archiving skills. Dexter specifically left me money to go back to college, because he felt I regretted not getting my degree, which wasn't true! I think he regretted not going to college himself! You know, he was very intelligent, an avid reader. But I promised him I'd return to my studies, so after he passed on, I went back to CUNY, and it was there that I met a professor who became my mentor, Dr. Cooper, who encouraged me to go to graduate school, where I became a McNair scholar. Ronald McNair was one of the astronauts killed in the Challenger space shuttle disaster, and the scholarship program named after him was set up for minority studies.

So I went to grad school, where I realized I needed to study historical methodology and research. I went to NYU in history and got a master's degree in Africana Studies, and then, in the PhD program, which I haven't completed yet. My area of study is the history of the African diaspora. The dissertation topic I'm working on is jazz-related: "Minton's Playhouse in the Early Period, 1938-1943" covering the early development of bebop. But all of this is really to prepare for the work I'm doing on Dexter's biography.

AAJ: That shows a great dedication—to put in such efforts. It reminds me of Robin Kelley's extensive preparation for his biography of Thelonious Monk.

AAJ: That shows a great dedication—to put in such efforts. It reminds me of Robin Kelley's extensive preparation for his biography of Thelonious Monk.MG: Actually, Robin was my adviser. I did the research for him on the San Juan Hill neighborhood in Manhattan where Monk came of age. But my biography of Dexter is somewhat different. I'm writing more of a cultural history, and a large part of the book is in Dexter's own words. He did a lot of writing—vignettes, letters. While he was in Europe, he wrote letters to Alfred Lion and Frank Wolff at Blue Note. I have placed all those letters, his and theirs, in the Library of Congress. I became an archivist, and put together three Dexter Gordon collections in the Library of Congress: first of all, his papers. Then, in Culpeper, Virginia is the recorded sound—all his CDs, tapes, and 78s. Finally, there are the letters, music manuscripts, photos, and documents. My research for Dexter's biography will utilize these collections extensively.

AAJ: What's in Culpeper?

MG: That's where they house the recorded sound of the United States. It's eight floors under the ground—it's called "Cheney's Bunker" because that's where he sought safety on 9/11. It used to be the Federal Reserve, but it now houses all the recorded sound of the U.S., from the very beginning, including films, records, everything.

AAJ: A highly protected environment for those fragile documents.

MG: Yes, it's all preserved and protected. I've retained the rights to Dexter's documents. They copy everything onto digital format, and they help me to get easy access to things as I need them. For example, if I need a copy of the concert Dexter did with the New York Philharmonic in 1987-88, then the next day I get a digital copy Fedexed to me. I learned a lot working on those collections with a wonderful former student from Columbia University named Jess Pinkham.

AAJ: Do you know when your biography of Dexter will be released?

MG: I hope to complete it this year and published next year, 2013, which will be the occasion of Dexter's 90th birthday. My agent is currently talking with various publishers.

Recalling Dexter Gordon and His Cohorts

Recalling Dexter Gordon and His CohortsAAJ: Let's talk about your memories of Dexter and his world. We know that he had his drug addictions at times, and he was also a victim of segregation and racism at various junctures of his life. Yet, he wasn't embittered by these experiences. Rather, he seems to have been a magnificent individual, generous and kind. Of course, he performed with many of the jazz greats. And for a long time, you were very close to him, traveled with him.

MG: Yes, I did. But at a certain point I really started spending 24 hours a day with him, what he called "the test of a real marriage." What happened was that we closed the office after some great successes with Woody Shaw, brought Johnny Griffin back from Europe for the 1978 concert in Carnegie Hall [Dexter Gordon: Live at Carnegie Hall (Columbia Legacy, 1979)]. Actually, Dexter did a prior concert there on September 23, 1977. It was produced by Max Gordon. It was sold out and then Max produced the second one in 1978.

By that time, we had what we called our "bebop empire." But then in 1983, when Dexter was 60, he said, "OK, enough. I need a break from all this traveling and career. I want to read some books! I need a break." So we closed the office on 35th Street between Park and Lexington Avenues. He said, "I want to have a normal life, spend time with you and Woody III [Gordon's stepson .]" People in the jazz business have no idea what a normal life is: breakfast, lunch, and dinner; walking your kid to school, and so on. In reality, having a family life is a really hard job. But he wanted to try it. One day someone said to me, "Oh, you don't work!" And Dexter shot back, "Don't you ever say that to her!" When Woody III was little, I was working. This kid was raised in the kitchen of the Village Vanguard. He loved drummer Victor Lewis, and they're close to this day. Back then, as a little kid, Woody would walk over to Victor Lewis, lie down, and go to sleep right next to the drums. Woody eventually became a drummer himself, although today he's primarily an administrator and producer.

Anyhow, Dexter and I took this break from work, and in the winter we would go to Cuernavaca, Mexico. We had a house there, and we would go there right after New Years, and come back in time for the baseball season. Dexter was a big baseball fan.

AAJ: What was his favorite baseball team?

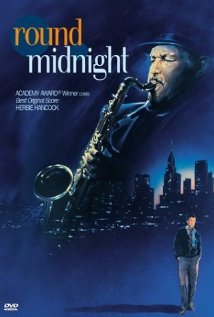

MG: He was a Mets fan. We'd go to Cuernavaca, pack up a duffle bag full of books and go. Once there, we had a lot of time to reflect on Dexter's life, what he had done, what he wanted to do. Dexter was an introvert, a quiet guy. He liked to read, watch baseball. He did a lot of socializing, but it didn't come naturally, and he considered it acting. When they offered him the acting job for Round Midnight, he said, "I've been acting all my life, so this is nothing new" [Gordon had actually done some acting work as a young man in Los Angeles].

Making the Film Round Midnight

AAJ: When and how did Dexter get the offer to do that film?

MG: It's almost a "Rashomon" type of story with different versions. Michael Cuscuna, Bruce Lundvall, and Bernard Tavernier [Director of Round Midnight] all remember it different ways. I'm going to L.A. in March and I want to get the producer Irwin Winkler's version of it. My own recollection is that we got the call from Bruce Lundvall, and Bruce told Dexter, "There's this guy who wants to make a movie about a jazz musician, and he wants to meet you." Dexter was skeptical, and said to Bruce, "Don't get too excited, because somebody always wants to make a movie about a jazz musician. It never works out." But Bruce insisted, and he sent a car to pick us up. We went to the Hotel Pierre to meet Irwin Winkler. Well, when he and Bernard Tavernier met Dexter, they said, "Oh my God, this guy is perfect!" But he had to do a screen test, and Warner Brothers had to OK it. Clint Eastwood was very helpful in getting Warner to budget for someone who'd never made a movie before to be in the lead role.

AAJ: As it turned out the movie was a big winner.

MG: Big success, big success.

AAJ: Clint Eastwood has done so much for jazz. He loves the music.

MG: He's great. I ran into him last fall at Sonny Rollins' concert in Monterey, and he was completely riveted by Sonny's playing, like everybody else there. The whole audience was completely transfixed.

AAJ: Since we're talking about Sonny Rollins, what contact, if any, did Dexter have with him, John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, George Coleman, and other saxophone icons who broke new ground like he did, but maybe in a different context?

MG: He listened to many of them. He loved Sonny, Wayne Shorter, Joe Henderson. By the time Dexter came back to the U.S., Coltrane was gone, but he did hear him at Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen with the John Coltrane Quartet. The story goes that Dexter gave Trane a mouthpiece that would help him project more. He was a big fan of Wayne Shorter, who was in Round Midnight. But I don't believe he performed with them. The only one he played with in that category was Johnny Griffin. Griffin came out of the Chicago scene, like Gene Ammons, who was Dexter's favorite tenor player. Gene and Dexter were in Billy Eckstine's band together.

Griffin was living in Europe when Dexter was there, so they would often do gigs together. He also did gigs with Ben Webster, whom he appreciated, and who lived in Copenhagen like Dexter. And he would go hear Ben often. In addition to being a player, Dexter was a big jazz fan. He used to say, "I'm a very lucky guy, because I'm a jazz fan, and grew up to be able to play jazz." He loved Lester Young, and often would go to hear him.

AAJ: Dexter is widely considered the successor to Lester Young.

MG: He said when he was a kid he would stand in front of a mirror and try to pretend he was Lester.

AAJ: Did he ever perform with Lester?

MG: No, but he met him, and they talked. Lester told Dexter how he liked the way he sounded, which thrilled Dexter. He was very close to Dizzy Gillespie. In 1988, they had a gig together on a cruise ship, the SS Norway, which is actually Dexter's last recorded performance. Clark Terry was there as well, and he was playing "Stardust," which Dexter never played, and he said, "C'mon Dexter, join in." Dexter declined, and Clark provoked him, saying, "Oh! Everyone says you can't play anymore." That made Dexter get his horn and play "Stardust!"

MG: No, but he met him, and they talked. Lester told Dexter how he liked the way he sounded, which thrilled Dexter. He was very close to Dizzy Gillespie. In 1988, they had a gig together on a cruise ship, the SS Norway, which is actually Dexter's last recorded performance. Clark Terry was there as well, and he was playing "Stardust," which Dexter never played, and he said, "C'mon Dexter, join in." Dexter declined, and Clark provoked him, saying, "Oh! Everyone says you can't play anymore." That made Dexter get his horn and play "Stardust!"On that ship, there were Dizzy, Milt Hinton, and others. Every night Dizzy and Dexter would have dinner together. Dexter died in 1990, and we talked about that trip until his last day. He and Dizzy would get into talking about the Billy Eckstine band as if it was just yesterday. The Eckstine band was 1945, and this was 1988, over forty years later, and they were talking in the present tense. Dexter asked Diz, "Why did Lucky [saxophonist Lucky Thompson] leave the band? And they'd talk about Art Blakey, Fats Navarro, Leo Parker. It was great. These musicians were so smart, so fabulous, so interesting. I'm a lucky girl to have been there with them.

AAJ: And you have also contributed so much to their efforts as well. As we're talking, it's fascinating to hear how much you are into the music and the musicians. It isn't just a business for you.

MG: No, it's never been just a business. I'm a jazz fan who got lucky to make a career around the musicians. But I don't want to overstate my contributions. I really just tried to do what the musicians wanted. Dexter knew exactly what he wanted to do, and it wasn't difficult for me to organize around it. And I had the best people working for me. For example, Hattie Gossett, the famous African American poet and writer, ran my office. I also learned a lot from Jack Whittemore, who was the best booking agent in the business. He had Ahmad Jamal, Stan Getz, Art Blakey, and Horace Silver on his list. He had been with Shaw Artists, and then he formed his own agency. When Dexter came back, I asked Jack to book for him, and, like Max Gordon, he initially refused, but said he would teach me to do it. He had me over to his office to show me the ropes. He was an old-fashioned Broadway guy who for some reason loved orchids. It was great fun to hang out with him, and when people like Blakey were around, it was terrific to be there.

AAJ: Didn't you say you were a big Art Blakey fan?

MG: I'm an honorary Jazz Messenger. I heard Art Blakey when I was fifteen years old, in 1957. I knew him from then on. One time, much later on, he called and said he was coming over to see me and Dexter. I got excited, went shopping, cooked a big meal, and Dexter interrupted me and pointed out, "He didn't say he was coming today!" I said, "Well, what if he does?" And of course, he didn't. He and Art had a big laugh over it when about a year later, the concierge in our building rang us up and said, "Art Blakey's here!" So he came up, and said, "I told you I was coming over!" And then he said to Dexter, "You might have married Maxine, but we raised her." I didn't know until then that he even noticed me way back when! It was thrilling to hear him say that.

AAJ: One of the most exciting musical experiences in the 1950s was to hear Blakey and the Jazz Messengers at one of their frequent Birdland gigs.

MG: With Lee Morgan and Wayne Shorter?

AAJ: Yes.

MG: That was an incredible band. You never forgot that, right? Even today, when I see Donald Harrison or Benny Green or any of those guys that played with Blakey, they still identify themselves with the Jazz Messengers. They've always kept that connection.

AAJ: Many players felt Blakey was the master mentor. He was a remarkable influence and developer of the musicians. Speaking of bands like the Jazz Messengers, I wonder whether Dexter himself ever tried to form a consistent working group. We know that he played consistently with many great musicians, but some musicians feel that leading their own group over an extended period of time is crucial to their development. Did Dexter consider that concept important?

MG: When he came back to the U.S. and he formed a band with George Cables, Rufus Reid, and Eddie Gladden, he felt he had his dream band and really felt he could develop with them. Cables said, "We have such good communication, so that by Dexter just looking at Rufus, he would know what was wanted." Dexter gave a lot of space to George and got a lot of ideas from what George was playing. Dexter finally felt he had his band.

AAJ: Cables is an amazing pianist and still very active.

MG: If anyone wants to know about Dexter, I tell them, "Call George." A guy from Montreal, a doctor, Bob Sunenblick always dreamt of having a Dexter Gordon recording on his own personal label. So he found this recording of the quartet [Dexter Gordon: Night Ballads: Montreal, 1977 (Uptown Records, 2012)], and I told George Cables, "I wanna give this guy permission to release this." When George heard it, he said, "Yeah, let's let him put it out." For the liner notes, I interviewed George and transcribed it. He talked about each tune, the band, and Dexter. Nobody is a bigger authority on Dexter than George. George spent a lot of time reflecting on how Dexter influenced him, even in the twenty years since Dexter died, and George has gone through a lot—he had both a liver and kidney transplant—and he's very reflective about his life and the meaning of life.

That recording is one of very few unreleased Dexter Gordon recordings we've permitted. We have a number of recordings in the Library of Congress, where you can stream them, but we're waiting for the right occasion and opportunity to release them as purchase-able recordings.

Maxine Gordon: Entrepreneur, Scholar, Writer

AAJ: Let's talk about you. Your credentials are very impressive: managing some top musicians, and a considerable amount of scholarly and research work in jazz and African American cultural history. You're serving as a senior interviewer and jazz researcher at Fordham University. You're a doctoral candidate at NYU, specializing in the African Diaspora.

AAJ: Let's talk about you. Your credentials are very impressive: managing some top musicians, and a considerable amount of scholarly and research work in jazz and African American cultural history. You're serving as a senior interviewer and jazz researcher at Fordham University. You're a doctoral candidate at NYU, specializing in the African Diaspora.MG: Right now, my primary focus is on completing Dexter's biography. Soon I have to go to Washington, DC to access the documents I donated to the Library of Congress—they think it's humorous that I have to do that; but the good part is that they have a finding aid so that if I have to look up, say, all of Dexter's contracts from the 1970s that document his itinerary when he came back to the States, they can pull that box out and bring me the papers. I have so many documents to go through, but I'm not Robin Kelley for God's sake!

AAJ: His research on Thelonious Monk was exhaustive and took fourteen years.

MG: Because of my research involvement, I've started going to conferences and giving talks, which is actually very helpful to my work. For example, I go to Istanbul, and they say, "Could you give a talk on jazz musicians in Europe in the 1960s, the so-called 'expatriate' period?" By the way, Dexter didn't like that term. One time James Baldwin got a hold of him and said, "Hey, Dex, a newspaper article referred to us as expatriates. I thought we were just living in Europe." Dex said to me, "I'm not ex-anything. Red Mitchell left the U.S. on account of the Vietnam War. He spoke up against U.S. policy, and went to Sweden. But for me, I had a gig in Europe, and before I looked up, it was fourteen years later. It wasn't political."

AAJ: Wasn't Dexter disillusioned with U.S. policy and attitudes towards black musicians?

MG: Of course he was. He was a member of the Black Panther Party in Copenhagen. He was active in his own way. He read the European Herald Tribune. When musicians would come over, he would ask them what's happening in the U.S. But for him it was about living the life of a jazz musician. He didn't feel he could do that in the U.S. at that time. He totally identified as a jazz musician. He liked the word jazz and thought it an honor. He was grateful that he could grow up and live that life and be around those people.

Researching the Jazz Scene in Harlem and the Bronx

AAJ: The cultural and geographical setting in which music takes place is interesting. For example, there were early developments in bebop taking place at Minton's in Harlem in the late 1930s and early 1940s. There were Dizzy and Monk. And in Harlem, guys would congregate at their apartments around the music. You've researched these developments in Harlem, as well as jazz specifically in the Bronx, NY.

MG: The research I did on Minton's tells us a lot. How Mary Lou Williams was so helpful to these guys in the development of bebop. Minton's happened to be the dining room of the Cecil Hotel. Mr. Minton was the first black delegate at Musician's Local 802. He installed a bar in the dining room. But downstairs, there was an afterhours club with a piano in it.

AAJ: That's where Monk and Dizzy often hung out.

MG: In Mary Lou Williams' archives, we found sheet music where, for instance, Charlie Christian would write out a tune.

AAJ: This would be in the late 1930s?

MG: Right, and Charlie Christian played an important role in bebop. What we have is a lead sheet where he wrote out the melody, and then in green ink, Mary Lou wrote out the chord changes in the bebop manner. She kept a diary in which she describes the people at Minton's. All this tells us how bebop developed much earlier than when it came to 52nd Street after World War II. Those iconic photos of Dizzy and Charlie Parker and the others playing on 52nd Street came quite a bit later.

So I did that research on Harlem, but then I was approached by Fordham University when they began their Bronx African American History Project with Mark Naison as the director. When they started interviewing the locals, people kept talking about jazz in the Bronx, and they needed someone to document that aspect of the history, and they offered me the job. We've accumulated hundreds of interviews with people in the Bronx, in the Morrisania section, where some people from Harlem had moved, only two subway stops away. And there was a lot of jazz there. There was Club 845. Dexter played in the Bronx. Sonny Rollins told me that he first heard Dexter in the Bronx. Musicians lived up there, trumpeter Oliver Beener, tenor saxophonist Harold Floyd Tina Brooks, they were local heroes in the Bronx. Some of them didn't have the biggest names, but they were great. Lots of music at clubs like Kenny's, Freddie's. The great saxophonist Lou Donaldson knows a lot about the Bronx, because he played at all those clubs.

AAJ: He still lives in the Bronx.

MG: Vocalist Maxine Sullivan performed in the Bronx, and we've studied her experiences there. She married the stride pianist Cliff Jackson. She ran an after school program called "The House that Jazz Built." She played a significant role in the social history of the Bronx. She was born in the Pittsburgh area, in Homestead, where the steel mills were, where Andrew Carnegie looked down on the workers in the steel mills from his mansion on the hill. They had a tribute to her in the Homestead library where they have a mini-Carnegie Hall. I was invited to talk about her and how important she is to the history of the Bronx. I met all her relatives, these women in the front row all dressed up, including her daughter Paula. I asked a lady next to me, "Where are all the men?" She said, "Oh, they're all dead because they worked in the steel mills [many died of asbestos-related pulmonary conditions]."

MG: Vocalist Maxine Sullivan performed in the Bronx, and we've studied her experiences there. She married the stride pianist Cliff Jackson. She ran an after school program called "The House that Jazz Built." She played a significant role in the social history of the Bronx. She was born in the Pittsburgh area, in Homestead, where the steel mills were, where Andrew Carnegie looked down on the workers in the steel mills from his mansion on the hill. They had a tribute to her in the Homestead library where they have a mini-Carnegie Hall. I was invited to talk about her and how important she is to the history of the Bronx. I met all her relatives, these women in the front row all dressed up, including her daughter Paula. I asked a lady next to me, "Where are all the men?" She said, "Oh, they're all dead because they worked in the steel mills [many died of asbestos-related pulmonary conditions]."Getting back to my interviews in the Bronx, I started out with the older people, for the obvious reason that they might not be here long, and they always say, "What took you so long to get here?" When you study black history, as they do for example at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Harlem is there, but the Bronx is not. Now, however, a lot of the research is being done by the Bronx County Historical Society.

AAJ: The history of the black neighborhoods in the big cities throughout the country is an important story that hasn't been fully documented. Clifford Brown's family lived in a neighborhood of black professionals and teachers in Wilmington. Dexter grew up in L.A., the son of a doctor. Anthony Branker came from a town in Northern New Jersey, the son of a devoted family. John Coltrane, Bennie Golson, and many others came of age in North Philadelphia. What black people accomplished in these neighborhoods and their spirituality and dignity despite segregation and other aspects of racism is extraordinary. And the sense of community was amazing.

MG: Think about Detroit, as well. It's a remarkable story.

The Special Relationship between Musicians and Their Fans

AAJ: Let's turn now to the fact that you've helped many of the musicians in a number of capacities. You're one of those figures, significant among them, women, who have supported them in their work and lives. For example, there is Sue Mingus, wife of the great Charles Mingus, who, like yourself, has supported her husband's legacy long after his passing. Art Pepper's wife, Laurie, helped him in manifold ways. Monk's wife, Nellie, for whom he named the tune "Crepuscule with Nellie," was utterly devoted to him and helped him navigate his tours in Europe. Then there was the Baroness Nica von Konigswarter, who befriended many of the musicians like Monk and Charlie Parker, took them into her home, and gave them sustenance and support in numerous situations. It's a very totalistic devotion, more than the typical spouse, friend, or relative provide. There's an amazing connection, even among jazz fans in general. What is that chemistry which leads people into such intense relationships to the musicians?

AAJ: Let's turn now to the fact that you've helped many of the musicians in a number of capacities. You're one of those figures, significant among them, women, who have supported them in their work and lives. For example, there is Sue Mingus, wife of the great Charles Mingus, who, like yourself, has supported her husband's legacy long after his passing. Art Pepper's wife, Laurie, helped him in manifold ways. Monk's wife, Nellie, for whom he named the tune "Crepuscule with Nellie," was utterly devoted to him and helped him navigate his tours in Europe. Then there was the Baroness Nica von Konigswarter, who befriended many of the musicians like Monk and Charlie Parker, took them into her home, and gave them sustenance and support in numerous situations. It's a very totalistic devotion, more than the typical spouse, friend, or relative provide. There's an amazing connection, even among jazz fans in general. What is that chemistry which leads people into such intense relationships to the musicians?MG: What you say is very true. I was with Dizzy Gillespie when he received the Kennedy Center Award. We were walking down the hall to the dinner, and a jazz fan came up and said, "Dizzy, you've meant so much to us, we're so happy you got this Award." Dizzy turned to me and said, "We know each other when we see each other. We have more in common with that guy that we don't know than we might have with some people in our families. We can meet a jazz fan anywhere in the world, and we can just say, 'Did you hear that tune, or that record, or what about that chord, or what about Elvin [drummer Elvin Jones]?'" Jazz even has its own language. I have a friend who is a professional basketball player and a jazz fan, and we went to Dizzy's Club Coca Cola, and a lady who was with us who knew nothing about jazz, said, "What language are you speaking?" She was confused because we were talking in code! He'd say, "Oh man, yeah Elvin!" You mention one word and it tells the whole story.

Once, my friend Irene and I went to Ghana, West Africa. It was 1973. And when we got to Accra and going through customs, I had these John Coltrane records with me. I brought them for my friend Jumma Santos, who was a drummer and percussionist working at the University there (Jumma recorded on Bitches Brew (Columbia, 1970) with Miles and worked with Jimi Hendrix, among many others). The customs guy said, "Oh, you like jazz? You've got to go to my brother's house, he's got a lot of recordings. I'm gonna call him to come get you." Irene said to me, "We don't know these people!" So the guy came, and he took us to his house, and he had all these records, but not the Coltrane recordings I brought, and he invited all these people and played them for them. So then we immediately had all these friends who were jazz fans.

I remember that one guy said to me, "Hey, there are six drummers on this record!" He pointed out the cymbal, the bass drum, the high hat, and the tom tom, thinking they were each played by a different drummer. It was, of course, all Elvin Jones. And when I told the guy, he said, "What part of Africa is he from?" And I said, "He's from Pontiac." Elvin loved it when I told him that story.

What jazz fans have in common with the musicians is listening. Eddie Locke told me that he was doing a gig with Roy Eldridge in New Hampshire, and hardly anyone came. So Eddie got lazy with the drumming, and Roy Eldridge stopped him and said, "I don't care if nobody's here! We're playin' some good music!" And Eddie said he never forgot that.

AAJ: In a way, the music is a devotion, a spiritual act that brings people together. It goes deeper than almost any other art form. There's a real sense of community.

MG: Facebook is an example of that. My son does Dexter's Facebook page, where there are over 33,000 Dexter Gordon fans, and they're so devoted and know so much about Dexter, and many of them write about "the first time I heard him"—and with the younger ones it's on a recording—it's unbelievable how they connect. And with Dexter it's his sound that captivates people. Also, Dexter was like us—he was a jazz fan. One time, he played at the Village Gate with Machito. A group of musicians were having a conversation in the dressing room. A woman journalist who couldn't get their lingo asked Dexter, "Do you understand what they're talking about?" He said, "Maxine can translate for you. She speaks bebop." [Laughter]

AAJ: There is a special language the musicians and speak in common.

MG: The historical tradition is also a source of commonality. Dexter would point out to me how, since I first got interested in jazz in 1957, I missed hearing a whole slew of jazz greats perform live, like Bird, and Billie Holiday, of course.

AAJ: The tradition lives in the music despite the changes. And we have recordings. But one does miss not having heard one or another player live in concert or at a nightclub.

MG: And the recordings don't always measure up to live performances. I heard Junior Cook on almost a daily basis when we were on tour together, and he was terrific night after night. But he suffered from claustrophobia, so in the recording studio, he was very uncomfortable. The truth is that if you never heard Junior Cook in person, you'll never know how great he was. He was very restrained on the recordings.

AAJ: Even the best recordings miss a dimension that you get when you're in the room experiencing the whole ambience of the performance. Now, to conclude, what's on tap for Maxine Gordon?

MG: On February 27, Dexter's birthday, I'm giving two talks at Brown University in Providence, RI. And I'm going to L.A. in March. In May, I'm going to the New Orleans Jazz Festival. Of course, I need to complete Dexter's biography. And when that's done, I plan to work on developing The Dexter Gordon Foundation, especially the educational component and preserving and disseminating Dexter's legacy, a task which my son Woody III is increasingly doing. I'm also planning my next book, which will be on Shirley Scott, Melba Liston, and Maxine Sullivan, a social history of three prominent women in jazz. They're three very important figures in jazz, and I'll include a fictive conversation on what they would say to each other now. Melba was very close to Dexter, who felt he learned so much from her. When he was a student in L.A., she did all the band arrangements. He loved her. He always called her "Mischievous Lady," and they hung out together until the end.

AAJ: You also mentioned Mary Lou Williams, one of the great women in jazz.

MG: Yes. Woody III is on the Board of The Mary Lou Williams Foundation, Inc. and I work with the Foundation in an advisory capacity. Woody handles their website.

Selected Discography

Dexter Gordon, Night Ballads: Montreal 1977 (Uptown Records. 2012)

Dexter Gordon, The Complete Columbia Albums Collection (Columbia Legacy, 2011)

Dexter Gordon, Round Midnight (Columbia, 1985)

Dexter Gordon, Gotham City (Columbia, 1980)

Dexter Gordon, Live at Carnegie Hall (Columbia, 1978)

Dexter Gordon, The Apartment (SteepleChase, 1974)

Dexter Gordon, Tangerine (Prestige, 1972)

Dexter Gordon, Body and Soul (Black Lion, 1967)

Dexter Gordon, Gettin' Around (Blue Note, 1965)

Dexter Gordon, Our Man in Paris (Blue Note, 1963)

Dexter Gordon, Go! (Blue Note. 1962)

Dexter Gordon, Doin' Allright (Blue Note, 1961)

Dexter Gordon, The Chase (Dial,1947)

Dexter Gordon, Long Tall Dexter (Savoy, 1946)

Photo Credits

Page 1: Courtesy of Sony Music Archives

Pages 2, 3: Francis Wolff

Page 5: Brian McMillen

Comments

Tags

Dexter Gordon

Interview

Victor L. Schermer

United States

Bud Powell

Lester Young

Woody Shaw

Melba Liston

Shirley Scott

MAXINE SULLIVAN

Art Blakey

John Coltrane

Harold Vick

Louis Hayes

Junior Cook

Ronnie Matthews

Stafford James

George Gruntz

Michael Cuscuna

Lionel Hampton

Hampton Hawes

Chico Hamilton

Eric Dolphy

Thelonious Monk

Johnny Griffin

Victor Lewis

Sonny Rollins

George Coleman

Wayne Shorter

Joe Henderson

Gene Ammons

ben webster

Dizzy Gillespie

Clark Terry

Milt Hinton

Billy Eckstine

Fats Navarro

Leo Parker

Ahmad Jamal

Stan Getz

Horace Silver

lee morgan

Donald Harrison

Benny Green

George Cables

Rufus Reid

Eddie Gladden

Red Mitchell

Mary Lou Williams

Charlie Christian

Charlie Parker

"Tina" Brooks

Lou Donaldson

Cliff Jackson

Clifford Brown

Anthony Branker

Charles Mingus

Art Pepper

Elvin Jones

Jimi Hendrix

Eddie Locke

Roy Eldridge

Machito

Billie Holiday

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.