Home » Jazz Articles » Rhythm In Every Guise » Max Roach on Clifford Brown's EmArcy Recordings

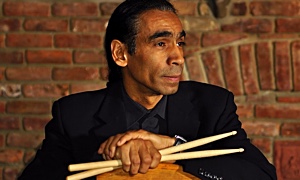

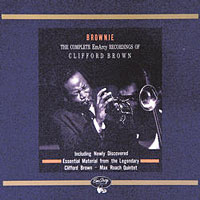

Max Roach on Clifford Brown's EmArcy Recordings

Because of Roach's brilliant technique and a penchant for taking extended, virtuosic solos, it's easy to lose sight of the variegated nature of his drumming, including saying a lot with only a few strokes; offering unobtrusive support to a soloist at low dynamic levels...

Max Roach's prodigious drumming in ensembles co-led by trumpeter Clifford Brown during the early-to-mid 1950s ranks as some of the most important work of his legendary six-decade career. Throughout the 97 tracks of Brownie: The Complete EmArcy Recordings Of Clifford Brown, Roach radiates power, keen intelligence, organizational flair, as well as exhibiting the capacity for rapid change. Nearly everything he plays exudes an air of utmost certainty. He balances the forceful and directive aspects of his artistry with finesse, flexibility, and a steady, patient character. Because of Roach's brilliant technique and a penchant for taking extended, virtuosic solos, it's easy to lose sight of the variegated nature of his drumming, including saying a lot with only a few strokes; offering unobtrusive support to a soloist at low dynamic levels; and evoking a multiplicity of textures from a four piece drum set and a few cymbals.

Max Roach's prodigious drumming in ensembles co-led by trumpeter Clifford Brown during the early-to-mid 1950s ranks as some of the most important work of his legendary six-decade career. Throughout the 97 tracks of Brownie: The Complete EmArcy Recordings Of Clifford Brown, Roach radiates power, keen intelligence, organizational flair, as well as exhibiting the capacity for rapid change. Nearly everything he plays exudes an air of utmost certainty. He balances the forceful and directive aspects of his artistry with finesse, flexibility, and a steady, patient character. Because of Roach's brilliant technique and a penchant for taking extended, virtuosic solos, it's easy to lose sight of the variegated nature of his drumming, including saying a lot with only a few strokes; offering unobtrusive support to a soloist at low dynamic levels; and evoking a multiplicity of textures from a four piece drum set and a few cymbals.Throughout solos by tenor saxophonist Harold Land and trumpeter Clifford Brown on "Delilah" (Disc 1, Track 1), Roach sustains an amiable swinging groove in an organized and imaginative manner. His drumming is firm but not especially potent or controlling; and he generally forsakes interaction in favor of a supportive role. Inside these parameters there's a good deal of color and variety. There's nothing random about what Roach is doing; he is thinking his way through each 8 bar section of the tune's 32 measure form. In synch with George Morrow's walking bass line, sometimes the bass drum carries the pulse; in other instances repetitive patterns (for example, combining rim knocks on beats 2 or 4 with bouncing 3 or 4 stroke figures to the floor tom-tom) aid in moving the band forward. He also employs an assortment of rhythms in ways that are not meant to draw attention but nonetheless exert an influence on the music. Snare drum patterns often have a quasi-shuffle feel and are executed with varying degrees of emphasis and volume. The occasional stout hit to the muffled bass drum sets-up or ends a sequence; and, in one instance, a three-note phrase on the snare marks the transition from one eight-bar section to the next. In some cases, eighth-note triplets executed with one stick serve as fills; in others, strokes to the low tom-tom push against the pulse.

Aside from straight four beats per measure, and intermittent shots that round out or complement his snare drum comping, Roach uses the bass drum in novel ways for extended periods. Four episodes during Land and Brown's solos on a medium tempo version of Bud Powell's "Parisian Thoroughfare" (Disc 1, Track 3) are prime examples of his use of the rock hard sound, both alone and in concert with other drums, to create patterns that have a powerful, and sometimes unsettling effect on the music. The flat muffled timbre of the drum is as important as the rhythms he plays. If it rang out or projected any more, its punchy effect would turn slack and ineffective. When he uses the big drum as a hefty contrast to every other component in his kit, precision remains one of Roach's central preoccupations.

Toward the end of Land's one chorus solo, four hits (three placed off of the beat, and one that lands squarely on the beat), spread out over the better part of three measures, constitute a phrase that throws its weight around without breaking up the music's overall flow. On the eighth bar of Brown's first chorus, Roach uses the bass drum at the end of four strokes to the floor tom-tom, just a shade before the downbeat of the next measure, sounding as if he's breaking a fall. A little later on Roach repeats a bucking two-note figure between the snare and bass drum that favors the bass for 4 bars. The lopsided line works against the pulse and swings in its own stubborn manner, matching Brown's accented blasts. Immediately before Brown's second chorus, Roach begins a simpler, repetitive riff, again lasting for 4 bars, using the bass drum (the snare strokes that surround it are scarcely audible) immediately before the first beat then squarely on the second beat of each measure. Its genial regularity punctuates Richie Powell's chords and the trumpeter's vivacious phrasing.

Roach's 32 bar solo on "Jordu" (Disc 1, Track 4) contains multiple elements, such as the meticulous tuning of his drums, versatile sticking and footwork, a cornucopia of rhythms, judicious pacing—none of which stands out to the detriment of the others. The traditional weaknesses of extended drum solos—lack of subtlety, technique for its own sake, little or no logical progress—don't apply here. A combination of spontaneity and calculated development, Roach's drumming is complex, yet it makes a visceral impact. Regardless of how fast and elaborate his sticking becomes at times, Roach is always in complete control of his limbs. He never rushes or overplays. Each drum is distinct and well defined; the sound of one drum doesn't "bleed" into another. The snare, mounted tom-tom, and floor tom-tom are tuned high, enabling him to build melodic phrasing into beats that swing with gusto.

For the first 16 bars of the solo the bass drum pads on 4 beats per bar. This steady, unobtrusive pulse enables Roach to introduce melodic ideas, moving from drum to drum and making the most of the contrasts between them. Roach states an idea just long enough for it to become familiar, and then moves on in a manner that doesn't sound forced or contrived. It's clear that he wants every stroke to be heard and that they all have a purpose. Varying the velocity of his rhythms, he moves from accents that occur every beat or two, to stuttering bunches of strokes, to rapid roller coaster-like trips around the drums.

At the solo's halfway mark there's a noticeable change. The bass drum now stomps on and off of the beat and is part of phrases that sound thickset, earthy, and adamant. Hitting the drums hard without losing his practiced touch, during 8 repetitions of a ½ bar cadence that begins and ends with the bass drum, Roach sounds like a gigantic machine that is slamming together a bunch of recalcitrant parts. He soon follows with four bars of continuous, snapping eighth-note triplets played by one stick, while underneath he strategically layers the simple yet swinging sound of the bullish bass drum and a lightly crashed cymbal in unison—as if to provide a release from the obsessive sound of the snare.

At the solo's halfway mark there's a noticeable change. The bass drum now stomps on and off of the beat and is part of phrases that sound thickset, earthy, and adamant. Hitting the drums hard without losing his practiced touch, during 8 repetitions of a ½ bar cadence that begins and ends with the bass drum, Roach sounds like a gigantic machine that is slamming together a bunch of recalcitrant parts. He soon follows with four bars of continuous, snapping eighth-note triplets played by one stick, while underneath he strategically layers the simple yet swinging sound of the bullish bass drum and a lightly crashed cymbal in unison—as if to provide a release from the obsessive sound of the snare.

During the head of "What Is This Thing Called Love" (Disc 5, Track 2), Roach's terse, chomping fills serve as a contrapuntal commentary to the mid-sized band's segmented rendition of the melody. He constantly varies the dynamics of the sticking and footwork—sometimes the strokes are faint and barely make an impact; in other instances, they're strident but not overwhelming. For the first sixteen bars Roach mixes a couple of different strains. The first is a snare drum stroke and cymbal crash in unison that falls after the band plays a phrase, and immediately before the downbeat of the next bar. The result is a controlled blast that creates the illusion of spinning the music in another direction without really changing its course. In other cases he'll place the bass drum and cymbal in different places for a similar effect. The second strain consists of brief, rough-hewn cadences that contrast the hard snap of the snare and the low, firm push of the bass drum. In listening to these relatively simple fills you can't help but think of some of the sounds and textures produced by the drummers in today's popular music. For the tune's bridge, Roach reverts to some of his standard comping patterns on the snare, dropping the volume and playing well under Herb Geller's alto saxophone. Saving the best for last, beginning on measure 27 he alternates between the snare and bass drum, hopscotching across bar lines in an insistent pattern, which lands both off and on the pulse. For a few seconds, until he once again defers to the horns, Roach dominates the music and gives the impression that this is what he's been working up to all along.

A jubilant rendition of Clifford Brown's composition, "The Blues Walk," (Disc 9, Track 8) contains up-tempo playing that is brilliantly conceived and executed. During Brown's first three solo choruses, the drummer displays three different rhythmic strategies, each essential in driving the band forward. Devoid of even the briefest digressions, his playing on the first chorus is a neat package. Recorded much better than on some of the earlier sessions, Roach's straight time on the ride cymbal lies slightly under the more prominent snap of the hi-hat cymbal on beats 2 and 4. Both are low enough in volume to enable George Morrow's bass to take the lead. On the chorus's 12th and final bar, he cuts loose with one stroke to the snare and two to the bass drum. Precise, weighty, decisive, every stroke placed for maximum effect, it is quintessential Roach. For the second chorus he keeps the ride cymbal and hi-hat in place and adds the snare, bass, and both tom-toms. With one exception, a melodic-sounding phrase between the bass and mounted tom-tom, every stroke is spread out and executed in a way that makes them sound like they're independently popping up out of nowhere. In doing so Roach creates a rhythmic dimension that is simultaneously a part of and outside of everything else in the music. In the middle of Brown's third chorus, the bass drum and tom-toms disappear, and he generates a more conventional, quasi-shuffle feel with dense bunches of strokes to the snare.

< Previous

Pulling Out All the Stops

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.