Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Libertango - The art and music of Leonardo Suarez Paz

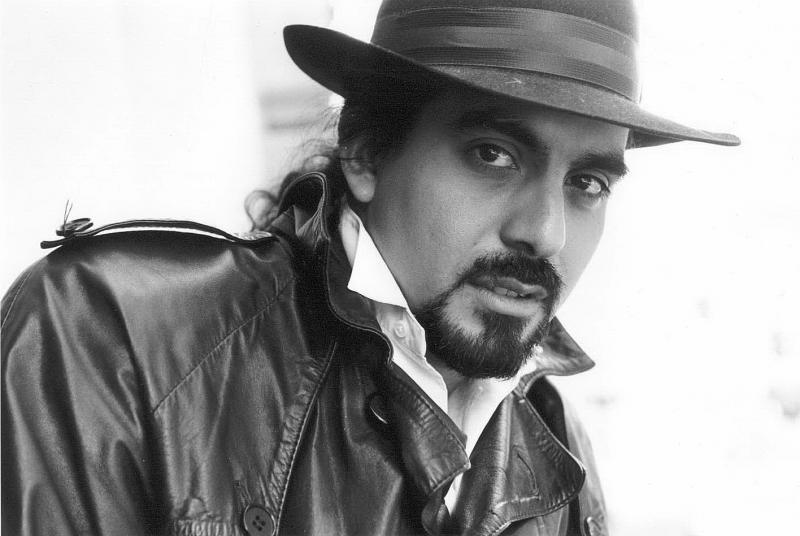

Libertango - The art and music of Leonardo Suarez Paz

It would be much easier for me, if the vibes of the sixties were present now. Now, it’s all about image, about trademark.

—Leonardo Suarez Paz

Leonardo Suarez Paz is tango royalty. His father Fernando played violin with Astor Piazzolla, the great tango composer and bandoneon player. His mother Beatriz is a famous singer within the music and, throughout Suarez Paz' childhood, the family home thronged with musicians, poets, dancers and artists. Now, he carries that mantle forward in his own music.

We talk via Skype, he in his apartment in that cultural melting pot of New York, whilst I sit in my study in that cultural wasteland of South Essex, where tango—if it means anything at all—means Strictly Come Dancing or a fizzy drink rich in artificial additives. "I want to show you something," Suarez Paz says and turns away from the screen. He produces the jaw of a shark and holds it close to the motion eye. There is writing in Spanish on the inside of the jaw. "I'll translate for you," he tells me, grinning at the memory. "Astor was a keen fisher of sharks and he gave me this when I was a boy. He always took a big interest in my violin studies and this says, 'Leonardo, if you do not study, the shark will eat you."

It must have been an incredible childhood. Yet having growing up in that milieu sometimes leaves Suarez Paz frustrated with the monoculture that is the music business today. "It is very strong in me and at times makes things more difficult," he says and pauses to find the right words, "because you understand about the freedom of creation and the world isn't about the freedom of creation now."

And he continues, "It changed. It is not the sixties anymore. They want to pigeonhole you. I play jazz. I play tango. I write and I arrange. I play classical, too. That should help but it does not. I dance and I sing. People don't understand that because you are only supposed to do one thing. I am not like that."

The contrast with the world of Suarez Paz' childhood and adolescence could not be greater, as he recalls, "I grew up in world where they were creating all the time. In my house, it was a centre—a hang out for composers and musicians. They were making barbecues and playing till six or seven in the morning. As children, we did not have any restriction. We could be sleeping there next to them. It was a beautiful experience and it was all about creation. People were creating lyrics, improvising lyrics as in rap right now. There were all these big poets like Ferrer (Horracio Ferrer). I grew up in all of that. I have to continue working through that line, which is very tough. It would be much easier for me, if the vibes of the sixties were present now. Now, it's all about image, about trademark." He almost spits out that last sentence.

My own introduction to tango came with a series of CDs made by Latvian violinist Gidon Kremer for Nonesuch in the late nineties. I mention this but Suarez Paz' response is instructive. "I respect him as a violinist a lot. He has a great technique and great expression and actually because he is an internationally famous musician, he played a very good part for the tango, because he played the music of Piazzolla. But if you want to go to the real sound you have to hear Piazzolla's own quintet. That's the only way to understand his music because Gidon Kremer...it is really clear that he listened to my father a lot but also it is really clear that it is not in his nature, that music. That's the situation with the tango. If you don't have it in your nature, it's a really big leap to really get this music."

For Suarez Paz, attempts by groups like Gotan Project and Tanghetto to bring tango to younger audiences achieve little of lasting benefit. It is rather like promoters and critics who pretend that cross-over artists bring young people to jazz. Few, very few, will make that journey, preferring just a taster or two on their MP3 player before deleting them for some new flavour or other.

But it is not that Suarez Paz lacks openness. He just hates the artificial and transitory nature of a business built on trading music like a commodity. He studied jazz in Argentina and, after all, as he points out Piazzolla himself moved to New York at one time living with fellow Argentineans saxophonist Gato Barbieri and pianist Lalo Schifrin in a studio apartment. Back then the great man harboured ambitions of becoming a jazz musician—there just weren't that many openings for a bandoneon player! In that respect, Leonardo Suarez Paz has surpassed his mentor.

Born in 1971, by the time he was nineteen, Suarez Paz was touring the world with a number of orchestras, including those of Mariano Mores and Atilio Stampone, as well as the acclaimed show Tango x 2. However, when he was contracted as violin soloist for the Broadway show, Tango Argentino, he relocated permanently to New York. For a while he developed parallel and intersecting careers as a jazz and as a tango violinist, performing Piazzolla's music at the Lincoln Center and jazz with drummer Cody Moffett's ensemble Jambalaya, playing on Moffett's My Favourite Things CD. French violinist, Jean-Luc Ponty is also a close friend and an inspiration.

There were other gigs with Stanley Jordan and with guitarist Jim Hall, the latter featuring Suarez Paz' tango group Cuartetango, which unfortunately went unrecorded. He also had considerable success with his own band, the Leonardo Suarez Paz Quintet and even had a five string violin made for him by Urban Strings—Argentina to allow him to play Coltrane-like lines on the instrument. Their only album, currently out-of-print, Scream features fine versions of the title track with some wild saxophone from Tito Puente and Chico O'Farrill alumnus Enrique Fernandez and a beautiful Latin-jazz "Giant Steps."

More recently, Suarez Paz has focused on tango music, including his Masters of Nuevo Tango project that brought together music, poetry, song and dance—all those elements from his childhood and home life -in one astonishing show. There is a clip on YouTube that features Suarez, père et fils or properly padre e hijo, in a duet that reveals just how powerful and sensual tango music can be.

I ask if he has plans to return to jazz. He hints at a possible jazz and tango CD that will explore the shared roots of both musics but, at the same time, his answer is both practical and shows his huge respect for the demands of playing jazz. "Perhaps I will return but it is a lot of practising," he explains, "because to play Coltrane lines on violin is like 'wow!.' I could do a book on his playing and how to do this on violin because it is very difficult. You have to restructure your technique."

Piazzolla's innovation in the fifties in tango music involved an emphasis on swing brought in from jazz and, perhaps, more importantly introduced a Bachian approach to counterpoint. Ironically, given his love of jazz, Piazzolla de-emphasised the role of improvisation in the tango. As Suarez Paz points out, "Piazzolla was crazy about playing what he think it had to be. That is why he started writing everything." At the same time, Piazzolla allowed Suarez Paz senior greater latitude here than some of the other musicians. However great the debt Leonardo Suarez Paz owes Piazzolla, increasingly he sees his own approach as bridging the older style of tango music and that of nuevo tango.

"Tango improvisation was earlier important with groups like Orquesta Francini-Pontier," he tells me. "It was an art form. I wanted to bring improvisation back into tango in a different form. When I am improvising—and I studied jazz improvisation a lot—I am not improvising jazz. I am improvising tango!"

Sadly, not only is Scream out of print but so too is Cuartetango's recording, L'atelier, on EMI Classics. However, Moffett's My Favourite Things is still around, as is Raul Jarena's Grammy nominated Tango Bar on Chesky Records, which features Suarez Paz on violin. But the 'must have' CD is Cuartetango's Masters of Bandoneon, with its rich panoply of guest performers, including Suarez Paz' mother and father. For those in England lucky enough to be in Leicester or Suffolk, this October offers two rare opportunities to hear Leonardo and his singer-dancer wife Olga live in the UK. They perform with the excellent London Tango Orchestra at Leicester's Night of Festivals on Friday 2nd October and again at Snape Maltings as part of the Flipside Festival on Saturday 3rd October. Then on Sunday 4th, Suarez Paz gives a lecture on Piazzolla and delivers a Tango Strings Workshop at The Joint Studios in London. The visit is made possible by Michael Becker's "Not For Profit" organisation, Innovative Giving Enhancement, for which Suarez Paz is Artistic Director. Suarez Paz describes tango as a movement rather than style and now, like his father and mother, he has become an ambassador for the music. "Gladly, yes," he says laughing. "The National Academy of Tango, one of the government academies, they voted unanimously to have me as one of their visiting academicians." It would be hard to think of hands—or feet! -more capable of assuming that role.

By the end of our interview, I realise have learnt more about this music than I could from a dozen books. Because tango is a music for dancing. It is classical music. It is dance and poetry and song. It is about the free, creative expression of the soul. It's about life—or rather what it can be.

Tags

Leonardo Suarez Paz

Interview

Duncan Heining

United Kingdom

London

Astor Piazzolla

Gidon Kremer

Gotan Project

Gato Barbieri

Lalo Schifrin

Cody Moffett

Jean-Luc Ponty

Stanley Jordan

Jim Hall

Tito Puente

Chico O'Farrill

Enrique Fernández

London Tango Orchestra

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

.jpg)