Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » James Lent: The Man at the Piano

James Lent: The Man at the Piano

For me, the ability of an artist to move the soul is of far greater importance than his level of technique.

The Other Side has been a landmark of Hyperion Avenue, sandwiched between a gymnasium and an eatery or two in the Silverlake section of Los Angeles, for several decades. Ownership has changed once or twice; bartenders have come and gone. But faithful patronage of the restaurant-bar hasn't waned.

The Other Side has been a landmark of Hyperion Avenue, sandwiched between a gymnasium and an eatery or two in the Silverlake section of Los Angeles, for several decades. Ownership has changed once or twice; bartenders have come and gone. But faithful patronage of the restaurant-bar hasn't waned. Inside, the blood-red walls are accented by soft lighting, black leather stools and white shuttered windows. The focal point of the room is a black piano framed by mirrored paneling. Six nights a week, six different pianists of various styles and personalities entertain the mostly over-50 crowd. For those who sing, the atmosphere is a welcoming one, allowing a decidedly mature group to belt show tunes, croon jazz standards, or wail the blues.

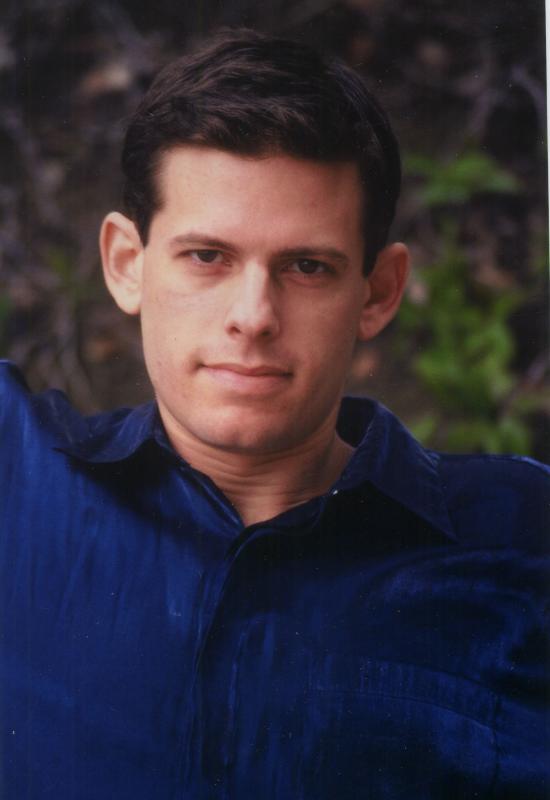

If there's one night that stands above the rest, it's Friday. Each week, classically-trained pianist James Lent employs his persuasive talents to coax singers of all ages and genres up to the mic. The fun grows steadily. Arriving at 9 p.m., Lent, slight and handsome, approaches the piano, quietly seats himself and prepares his first selection. Usually, it's Gershwin's immortal "Rhapsody in Blue." Occasionally, it's Debussy's "Clair de Lune." During the holiday season, it might be Tchaikovsky's "The Nutcracker Suite." But whatever the choice, Lent melts into his opening notes with class, grace and ease.

But elitists beware: Lent will invariably segue into Jimmy Buffet's "Margaritaville," the theme song from TV's The Brady Bunch, and even the Doris Day chestnut, "Que Sera, Sera." Patrons have only one defense—to sing along. And, of course, that's the idea. For Lent, it seems, is on a mission: to get the room rocking.

Lent's singing isn't his first talent. Still, he can ably carry a tune, his voice charming and infectious. The singers who follow tackle everything from Johnny Mercer to Journey. Sprinkled in between, is Lent's own arrangement of "The Pink Panther Themes," as well as irreverent takes on the most beloved of classics, including "Oklahoma!" ("Old Glaucoma!").

Indeed, with Lent helming Friday nights, life truly is a cabaret.

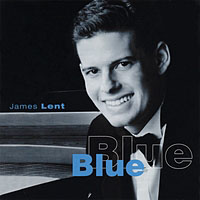

Lent came to the bar in 2002, before which, he was already a deeply respected concert soloist, teacher, and graduate of Yale University where he earned his doctorate of musical arts degree in 2000. That same year, he released his highly-acclaimed debut CD, Blue (Self Produced, 2000). Lent's numerous piano awards include prizes in the National Chopin Competition, the Salon de Virtuosi Awards, and the title of Top Instrumentalist in the World Championships for the Performing Arts in Burbank, CA. Lent continues to perform locally and throughout the world. Yet despite his prodigious talent, he remains a thoughtful and self-effacing man.

All About Jazz: So you're a native of Houston.

James Lent: Yes.

AAJ: What's it like for a highly-gifted Jewish boy to grow up in Texas?

JL: I never felt that Jewish when I was growing up. It was something my family pushed upon me when I was eight or nine. I took Hebrew classes for a few weeks...it seemed my grandmother was more a part of making me Jewish than anything. Her priorities seemed to shift and it seemed the whole Jewish thing became much more in the background by the time I was 10 or 11. And then piano sort of overtook that. [laughing] Piano became my religion over being Jewish!

AAJ: Do you have any siblings?

JL: I have a younger sister.

AAJ: In the liner notes for your terrific CD—which I'll get into later—you mention that your great-grandmother held the distinction of being the only other pianist in your family. I found that surprising. Anyone else in your family musical?

JL: Not at all; she was the only one. She died in 1991, I believe, when I was in my sophomore year in high school. I inherited her Steinway piano. She was a large part of my sticking with it during times when I wasn't sure. I started playing piano when I was eight, and the first year it was like I was soaring faster than the speed of light.

My parents didn't understand how I got from book one to six of Edna Mae Burnham in a year. I just ate it up. It was fascinating to me. And it was largely due to our neighbor across the street who had a piano. I mean, we didn't have a piano!

AAJ: Really?

JL: No. And our neighbors next door had a son and daughter who were taking piano lessons. So watching them got me intrigued. Then I got a little electric keyboard for Christmas that played one octave—one note at a time. And it was only a little bit more than a week when I was picking out tunes from the radio and playing them. My parents would say, "Oh, I recognize that." And I was just doing this by ear.

JL: No. And our neighbors next door had a son and daughter who were taking piano lessons. So watching them got me intrigued. Then I got a little electric keyboard for Christmas that played one octave—one note at a time. And it was only a little bit more than a week when I was picking out tunes from the radio and playing them. My parents would say, "Oh, I recognize that." And I was just doing this by ear. The neighbor across the street—she was a lovely retired lady—offered to give me lessons for practically nothing. I was having daily lessons. Two years of that. And I have to say that, for a beginner, there's no better way to start than daily lessons because it's such a complex language, that if you don't have someone who's investing everyday into making sure you're on the right track, once a week's not going to cut it. And I loved the attention!

This was during a period in Roseville, California. I also spent some time in Tempe, Arizona, then I was back in Houston by sixth grade. There was some instability in my family. Music was a great escape from all that. Having two years of immersion was the most amazing thing in the world.

I studied for five years with my next teacher, who was of Russian descent and had Julliard training. He was intensely inspiring. After that, I went to Houston High School of the Performing Arts and started studying with a teacher who was producing all the competition winners. And that's when I started to become very competitive as a pianist. And then competition piano kind of took over from then until the end of my degrees at Yale.

AAJ: Do you recall your first performance?

AAJ: Do you recall your first performance? JL: It was some version of "The Entertainer" in some piano recital in Arizona. I also remember playing "The Winds of War" theme, which was my mother's favorite. I played it in a choir concert in middle school. I was accompanying the choirs. And as a reward for this, I got to solo a few times in those concerts. I remember doing some strange things, like a medley of TV themes and other off the wall stuff.

AAJ: Were there any other musical instruments that fascinated you?

JL: I had six months of guitar before I started playing the piano. But the calluses were killing me! I was miserable.

AAJ: Did you know at the age of eight that this was what you wanted to do in life?

JL: [laughing] Nah, I was just looking for an escape!

AAJ: As a child, were you introverted or extroverted? I'm envisioning "Schroeder" from Peanuts.

JL: I was pretty introverted during my formative years as a pianist. But when I got into junior high school, I was enrolled in choir to sing. I wanted to work on my voice. In a matter of weeks, my teacher put me into piano and kept me there.

Then I started playing for every choir, then he had me playing for every student in solo and ensemble. I was already making money at the piano at the end of my sixth grade year. I started doing these summer theater productions, which became winter theatre productions—kid and teen shows, with like 60 different musical numbers for each. I was getting paid to this—and paid very well.

Then I realized there wasn't anywhere to buy snacks for the rehearsals for these shows. So I had my parents buy snacks in bulks. So not only was I making money at the piano, I had my own concession stand! [laughing] This was seventh grade! That whole experience brought me out of myself.

AAJ: Houston's High School for the Performing arts must've been something—all those talented kids.

JL: That's when I started to get a more rigid kind of training. I had a real diversified experience. I had a very intense classical program. I was playing for musical theater productions. I was playing talent shows. The orchestra in the jazz band would use me—it was a little bit of everything. And I would've never excelled in one category had I not gone all the way through the doctorate in classical piano.

AAJ: Was classical your initial passion in music?

JL: I hated classical as a kid. I started to appreciate it as a listener my sophomore year in high school. But the thing that always baffled me about it was it took so much more effort to learn a classical piece of music. And most people in the world didn't seem to care. Whereas I could play these show and jazz tunes for these kids and get all this attention and make money! It was so backwards in my head.

I would have to struggle and practice to produce a three-minute piece of classical music nobody really cared about and no one would pay for. And I saw this at age 13! But my teachers told me if I was going to make it, I'd have to get the classical thing down. And my parents couldn't have cared less—they hated classical! But they listened to my teachers.

AAJ: In your liner notes, you mention your affinity for Aaron Copland. When did you first discover him?

JL: When I was young, I really didn't like Copland. But in high school, I got to play the ballet suite, "Rodeo," in a brief piano solo. I thought Copland was kind of cool then. But all other Copland bored me to tears.

But when I was teaching in South Carolina, a student named Kathryn chose the "Four Piano Blues" for a competition. And something magical happened to me. I still remember getting goose bumps hearing her play that movement. And I remember thinking, "how did I get a doctorate at Yale and never stumble upon this piece?" And when I was preparing my CD, Blue, I knew I had to record it.

I remember there was a time problem. I was finishing my course work at Yale, I was about to go on tour and I needed a product to sell to audiences I was performing for. And Sprague Hall was about to be closed down for about nine months for renovation. And I wasn't the only person who wanted to record there. And I realized that I'd better grab it if I was going to have a product. And it had better be a product people would want to buy. And I thought "Rhapsody in Blue" would be the best-selling thing I could produce. And I knew I had to include the Copland piece.

AAJ: In your own words, describe what you think is Gershwin's greatest influence on jazz?

JL: In terms of totality, he really didn't write all that much, at least compared to many other composers. He has a handful of musicals, he has Porgy and Bess, which is either a musical or an opera, depending upon how you look at it. He was one of the first people to blur the lines between classical, pop and African rhythms. He was really the first person to hybridize music, which became the trend forever after.

AAJ: Oscar Levant, who was also a close friend of Gershwin's, was one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century. Did he influence you?

JL: You know, I've been told constantly that I emulate Levant, yet the truth is, I still haven't gotten around to listening to his recordings. Certainly he was the greatest interpreter of Gershwin. And, strangely, there's a part of me that wants to keep him a mystery, as I really don't want to know. But I realize by reputation how important he is to the Gershwin catalogue, so I'm always flattered when I hear this.

I don't spend a lot of time these days listening to other pianists. And perhaps if I do, it's for jazz, as I still feel that of all the genres, this is the category I could step up my game. Now some people will say, either you've got it or you don't, but I don't think that's true. I believe almost anything can be taught.

AAJ: But you can't teach talent.

JL: Well, I was beat in piano competitions by some pretty untalented people. But they had great teachers. And there were times when I beat more talented people. So it takes a combination of a lot of things to produce the product.

Talent, in my opinion, is only about 15 percent of the equation. Determination, hard work, motivation and brute force work. If you hit your head on the wall long enough, you can eventually do the hardest thing one can do on the piano—if you're given the right guidance and the right information.

AAJ: Both Copland and Gershwin were Jewish at a time when it could be highly problematic to be Jewish. It was a very different time. Do you feel any connection to these men that goes beyond music?

JL: Again, I never really thought of myself as Jewish. And I don't think their being Jewish affected their music necessarily. Culturally, perhaps, but that was more the culture of the times in general, rather than for being Jews.

AAJ: What about Leonard Bernstein?

JL: [laughing] Oh, yes, he was certainly a person I would associate with being Jewish!

AAJ: No, no, I mean did he influence you?

JL: When I was 16, I got to see him in Boston. And that excited me. At that age, I really didn't know why he was so important. And it was at a time when I really wasn't sure if I liked classical music or not. But watching him conduct and seeing the excitement he brought out of the orchestra was a pivotal moment for me in deciding I liked classical music. He was definitely an inspiration for me to major in classical.

AAJ: Was it always your intention to get your doctorate?

JL: [laughing] No, it was totally an accident! After I finished my bachelor's in Houston, I didn't know what to do next. Everyone was telling me to go to Julliard. And I knew I needed to get out of Houston because I knew I had already done everything I could there. It wasn't bad. I was making a lot of money and I was well-known as an accompanist. But I knew if I wanted to grow, I would have to do the East Coast thing.

The summer before my senior year at the University of Houston, I studied at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara. And that's where I was in a class of 10 piano students who were from every major school on the East Coast—Julliard, Curtis, Peabody, etc. It was a great sampling and I got to hear about what goes on at these schools.

It was the most amazing kind of college fair for someone who specialized in piano. I developed the most excitement for Yale. And it just worked out that Yale gave me the best offer and they became my first choice.

AAJ: Let's talk about your CD Blue. This is a beautiful collection. Did you over-record, then narrow down your selections, or did you streamline your list beforehand?

JL: No, I was pretty much set on a list of music. Due to the time crunch, I was literally given six hours to record—two days, three hours each. I knew that "Rhapsody in Blue" was the most important, and had to get done first. I was really exhausted after that, as it's the longest track and the most demanding track. Then we went to the next difficult pieces—Strauss and Tchaikovsky.

AAJ: Let's discuss the tracks. You open with the Strauss classic "By the Beautiful Danube," transcribed by Andrei Schulz-Elver. You mention that this piece suffered from overexposure in the early part of the 20th century, resulting in a dormancy. Can you elaborate?

JL: Nothing this flashy had ever been written. And it became so popular that every pianist was trying to learn it. And people just got tired of it. And it sort of faded into obscurity after that. And nobody wanted to touch it. It became too common.

AAJ: Why did you choose it?

JL: I remember I was preparing for this major competition in New York—which eventually got me management—and I figured out that I needed that piece in my lineup in order to stand up against my competition. And I got super-motivated to learn it. And it's become a staple in my repertoire ever since.

AAJ: The opening notes on the piece are stunning, a true showcase for your dexterity and precision.

JL: It's about as flashy an introduction you can get. I recall being completely mesmerized by the virtuosity of that introduction. And it's those pieces of music—things that sound like an insurmountable challenge—that make you determined to learn them. I had that kind of attraction to that piece.

AAJ: The jazz flavor is very evident in the Copland section of "With Bounce." It's interesting the way the CD starts classical, then segues into "Four Piano Blues." "Freely Poetic" is just gorgeous.

AAJ: The jazz flavor is very evident in the Copland section of "With Bounce." It's interesting the way the CD starts classical, then segues into "Four Piano Blues." "Freely Poetic" is just gorgeous. JL: Yes, that section is a favorite of mine.

AAJ: You also include Rzewski's "Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues." Very esoteric piece.

JL: You almost have to see it to understand it. Because if you can see what's going on physically, it brings on a different effect. The piece was written to simulate the machinery of the cotton mill. So you play certain clusters of notes with your entire forearm. Just like the machine. And when you're watching someone do it, it's so visually effective. Like theatre.

For me, extreme dissonance and modernism are as a part of my personality as beauty and simplicity. Both extremes are very much a part of my musical being. I wouldn't have felt this CD represented me fully without that track.

That was the hardest representation of Blue I could find, whereas the third movement of Copland was the most pristine and serene. I felt that both ends of the spectrum had to exist.

AAJ: You named the album after your favorite color. Why is blue your favorite?

JL: I think there's always been an aquatic, blue part of me. It's kind of centering...calming.

AAJ: The album concludes with "Rhapsody in Blue," a performance that is clean, concise and brilliant. What struck me about the CD overall is it serves as both a demonstration of your abilities and tastes, as well as providing the listener with a highly satisfying array of musical sensibilities. It doesn't play as a demo, but rather as a complete entity.

JL: That's nice to hear. I chose my selections very carefully.

AAJ: I want to talk a bit about your performance at Carnegie Hall, which you did even before completing your doctorate. What are you memories of that experience?

JL: I was very, very nervous. And I don't get nervous! [laughing] It came about through luck and perseverance, and the right people recommending me for the right thing at the right time and place.

At the time, the winners of the Concert Artist Guild's Management Competition in New York were all featured at Carnegie Hall. It was just part of the deal. It all happened really fast. It was a month from the time I found out it was going to happen until the performance. So I had no time to plan what I was going to play, so I just had to ride on my strongest pieces of the moment.

AAJ: What did you play there?

JL: I had a 20-minute set. Liszt's "Valle d' Obermann" was one of my favorite pieces of that time period, so I included that. That took up most of my time. I included two other short pieces, but I don't remember what they were. But the Liszt piece was the big one.

AAJ: After completing your doctorate, you relocated to Los Angeles. I would've thought New York would've offered a greater cultural landscape.

JL: Well, I spent three years in New York after Yale. It was also during that time period that I commuted to Greenville, S.C., to teach. So I was spending four days every two weeks in Greenville and the other 10 days in New York.

I was also accompanying at Julliard, and I also had management that was taking me out of New York to do concerts. But soon I began to realize that every place but New York seemed to appreciate me so much more, both financially and in terms of response. And it's because there are ten times as many qualified pianists in New York than anywhere else. Everyone goes there.

After three years of that, I thought about how I felt in Houston. I wanted something like Houston, and for me...L.A. was a chance to have that. The final tour of my New York management took me to the West Coast for three weeks. That was nine years ago, and I've had no itch to leave since.

AAJ: In 2002, you started your Friday night gig at The Other Side. How did you land that?

JL: That was a result of the most loyal patron of the bar, who was also good friends with the owner. His name was Steve Dounard and, unfortunately, he passed at the early age of 62 four years ago. He lived a block away and would buy everyone their drinks.

A vacancy ensued on Friday night and they kept flipping different people, but nothing was really working even though the audiences were still decent. Friday was always a popular night to go to the piano bar. There was a period—I believe—when Michael Feinstein had Friday nights at The Other Side. This was, like, 30 years ago. Some pretty big people had Friday nights.

Steve was determined to find the right person for Fridays because he was so in love with that bar. He went online and found me on gigmasters.com. He pulled me in for an audition and I played "The Entertainer," "The Pink Panther Variations" and "Give my Regards to Broadway." I also brought in patriotic music, as it was the Fourth of July. But I didn't sing a note.

AAJ: Why didn't you sing?

JL: Because I couldn't! [laughing] I just flat out couldn't. My voice was so bad, that the first time I tried to sing, half the room left. And I was told not to sing again. I accepted it because I knew I couldn't sing. But it was okay because people liked me—as a pianist and a personality.

There was a random singer who popped in and sort of became my "guest singer." He was a tenor named Peter. And he was pretty much the major voice on Friday nights—for a year. I didn't know it, but Steve was paying Peter! But after a year, people were getting tired of Peter because he was singing the same songs.

Steve suggested we have auditions for guest singers and he would pay them. So I posted something on Craigslist and I was flooded with something like 60 auditions in a three-week period. And Steve got to be the judge, since he was the one footing the bill.

AAJ: I didn't know the singers were paid there.

AAJ: I didn't know the singers were paid there. JL: They're generally not! But Steve said if I were to make Friday nights into what they could and should be, there was going to have to be some paying of singers.

AAJ: This is surprising—a shortage of singers who'll sing for free??

JL: Well, there was a problem in marketing my night and what to call it. Some people associate it with old man piano bar, which is a turnoff; others associate it with karaoke, so that's a turnoff. It's none of those things. It's a strange mixture of everything all in one.

I've put some young people into the mix. It defies description and even now, it's hard to market something you can't describe. People just started coming in out of the woodwork to sing for free. And from that, something grew. But it took a little bit of manipulating to get things going. Steve got some nice reviews printed and really did some amazing promotional things for me in my first five years.

Suddenly, Steve died and I was faced with a lot of challenges because all those guest singers that were being paid by Steve I didn't want to let go. But I couldn't afford to pay them what Steve was paying them.

AAJ: You were paying them out of your own pocket??

JL: I didn't know what to do! I was at a total loss. Steve didn't leave a provision for me in his will. If he had known he was going to die at 62, he would've done so, I can tell you that. So I tried all sorts of things. But I did it and it still works. We now have enough singers who will sing for free.

AAJ: You told me you monitor the amount of ballads.

JL: Oh, yeah—I control that very carefully. Half of the singers now have enough of a rapport with me that they know what to sing and what not to sing at certain times. I'm much more ballad-friendly in the first 30 minutes, or after midnight. But in that primetime from 9:30 to 12, it's got be a ratio of three up-tempos to one ballad. And the singers understand this.

AAJ: Alongside this popular gig, you've managed to keep busy with other assignments. I know you replaced Andre Watts as a concerto soloist in the Alabama Symphony, performing Rachmaninoff's "Concerto #2." How did that come about?

JL: Oh, that was back in 2001. In fact, it was 9/11. If you recall, the planes were grounded for a week after the attack. But the concert was still scheduled for September 15th in Birmingham, Ala., with Andre Watts.

He was scheduled to fly in the day before the concert, rehearse with them and then do the performance. Obviously, he couldn't fly in. I was teaching in Greenville and my management got a call desperately looking for someone who could handle Rachmaninoff's "Concerto #2." And they told them I was teaching just three hours away. And I got the gig because I was in the right place at the right time. Plus, I was teaching the third movement of the piece to one of my students for a competition at the time, so I had the hardest part of it still fresh in my head.

I had played the first and second movements in '93 for my graduating recitals and hadn't touched them too much since. I remembered a method called "cheat sheets." This is when you take the parts of the piece you're most nervous about, shrink them down to really small print, hide them inside the piano, and lay it out in such a way that you only have to touch the pages between movements.

At the crucial moment, you raise your right hand with a handkerchief, wipe your brow, and then you put the handkerchief in the piano at the same time you make your switch and the audience is none the wiser.

AAJ: You must've been nervous.

JL: It all happened too fast to get nervous. It was just excitement! I was just on fire to be in such a situation. It went really well and I got a great review. I just wish it could've been recorded, but Union restrictions prevented that.

I have to say that certain things in life have come to me ever since as a result of that experience. For example, I got play Rachmaninoff 2 in China a little over a year ago. And this was due to that great review when I replaced Watts. They had a cancellation in China and had three weeks to fill it. They figured if I could replace Watts in less than 24 hours' notice, I could do it in three weeks! [laughing] I was really lucky that I was able to video that performance in China and that it went well.

AAJ: You coached actor Woody Harrelson for the film Seven Pounds. What was it like to work with him?

JL: Oh, he was awesome. He was super-eager to learn; very friendly, very fun. He had three pieces to learn and had been working with my former instructor, Jonathan Feldman, who had taught at Julliard. He told Jonathan he was going to be in L.A. for a week and would need more work and would he recommend someone. So Jonathan referred him to me and Woody took the suggestion to Sony, who hired me to work with Woody for the week before shooting, as well as be on the set during the shoot.

Woody at first thought he only had to do two things—the Mozart fantasy in C minor and a pop song, which I can't recall at the moment. But then they added a third piece, a sonata, and he was really stressing about it.

AAJ: How long did you work with him each day?

AAJ: How long did you work with him each day? JL: We worked for two hours a day for the week. And then the day before the shoot, he was starting to panic, so we had a four-hour session. He's definitely one who thrives on biting off more than he can chew, and I don't know how he doesn't let the stress get to him.

It was interesting to be part of his puzzle during that period because I could tell that there was a part of him that embraced the challenge, but there was a part of him that was like, "I'm never gong to be a pianist [laughing], so why am I doing this??

AAJ: Was he intimidated by you?

JL: Oh, no. First of all, he had been working with Jonathan, who recommended me. Secondly, I didn't play anything for him until the very end of our time together. I kind of taught him the way you'd teach a 12 year-old.

There's a certain methodology you use with younger students to keep them from fearing the instrument. If you set the bar too high, they freak out. So I kind of had to use those teaching techniques with Woody Harrelson. I do remember that at the very end of our time together, I started to notice that his own psychology was getting the best of him. At that moment, I knew I needed to somehow clear his head of whatever garbage was pulling him down.

I said, "Woody...sit on the couch, I've got something to play for you." So I pulled out the "Pink Panther Variations." My introduction to this was the Cheers theme. So I got him to laugh. And suddenly his attitude changed. It was like he was thinking, "Well, if you can do that, I can do this." So we got him there.

AAJ: Now, in the movies, don't they prerecord the music sequences?

JL: Yes. They used professional recordings for the movie and the shoot. So I had to teach him the precise hand movements. Now they could've used hand doubles, but they wanted a much more authentic look for this. So it was challenging.

AAJ: Let's go back to Gershwin for a minute. It's been said that the only composer in popular music to equal him is Richard Rogers. Do you share this sentiment?

JL: [thinking about it] Rogers has never been my favorite composer, but I would put him in the top three. He's given us some great melodies.

AAJ: His association with Lorenz Hart is akin to the Gershwin Brothers in that there's a crudeness in the lyrics which complements the sweet melody lines. Oscar Hammerstein's lyrics aren't nearly as sardonic. Yet the Rogers and Hammerstein shows have endured with greater popularity. Do you have a preference for Hart or Hammerstein?

JL: I would say the Hammerstein association, as their shows, and therefore their songs from these shows, have withstood the test of time better. But as far as intricate melody, Gershwin stands alone in popular music.

AAJ: Last year we lost two jazz legends: Lena Horne and, more recently, Billy Taylor. Taylor made a name for himself alongside Miles Davis and Charlie Parker. He was among the first to erase the image of jazz performers as ignorant and uneducated. Any influence for you there?

JL: Oh, yeah, I've got one of his books on piano transcriptions. Only about 10 years ago did they print out the transcriptions so that someone like me could read the music of what those jazz greats were doing. I would say that was one of the important parts of my jazz training...just going in and playing transcriptions by Oscar Peterson, Art Tatum, Bill Evans and, of course, Billy Taylor.

AAJ: Horne was accused of singing "white" in her early career before finding her ethnic voice later in life. Yet she's never been held in the same regard as, say, Sarah Vaughan, Billie Holiday or Ella Fitzgerald. Do you think she was viewed as a sell-out, especially after marrying white arranger Lennie Hayton?

JL: Yeah, she was never looked at as the "black singer." It's like, early on, she wasn't viewed as authentic. And I think when it comes to jazz singing, our public expects it to be a "real" black performer. And I think the fact that she waited so long to embrace her ethnicity was against her in that field.

AAJ: Your website lists quite an array of musical styles—everything from classical to jazz, to ragtime to top-40. You seem to embrace all kinds of music. And you appear to genuinely enjoy this variety. It's more than being practical. For instance, you've said that two of your all-time favorite songs are Donna Summer's "Last Dance" and the pop ballad "Since I Fell for You."

JL: Yes. They're both pop songs, but there's a great contrast in flavor and mood within those songs themselves. It's just good songwriting.

AAJ: You shocked me when you told me you like rap and hip-hop.

JL: I like it for the rhythmic interest...I like it because...there was a time when I had this whole trajectory of trying to sing and could not sing. I mean, I went on this journey at the piano bar from not singing at all to singing a fair amount. And part of that journey required my finding comedy songs that I could pull off that didn't require a lot of singing voice. Even now I don't try to do what I know I don't do as well as others.

For me, rap was a really easy way to bridge that gap of fear I had about singing. I've always thought that rap is an intermediate ground for the person who's afraid to sing. And it's part of our culture. It's easier to start rapping than it is to start singing. And people relate to it. Rapping is sort of like the first steps towards singing. And the really bright rap music can get a crowd going.

AAJ: The days of Gershwin, Harold Arlen, Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern and the like are often referred to as the "Gold Rush days." Do you think we'll ever have popular songwriting of this quality again?

AAJ: The days of Gershwin, Harold Arlen, Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern and the like are often referred to as the "Gold Rush days." Do you think we'll ever have popular songwriting of this quality again? JL: Never. It's unfortunate, but there are several reasons for this. Our music industry has changed so dramatically in the last 10 years. It isn't lasting. We've gone from flavor of the year, to flavor of the month, to flavor of the week, to flavor of the day. Nothing is sticking. And I don't think there's going to be the opportunity again that we had in the early 1900s for something to become as important as "Rhapsody in Blue."

< Previous

The Prairie Prophet

Comments

Tags

James Lent

Interview

Gary Bennett

United States

Lena Horne

Billy Taylor

Miles Davis

Charlie Parker

oscar peterson

Art Tatum

Bill Evans

Sarah Vaughan

Billie Holiday

Ella Fitzgerald

Harold Arlen

Irving Berlin

Jerome Kern

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.