Home » Jazz Articles » First Time I Saw » Incomparably Quiet: Bill Evans

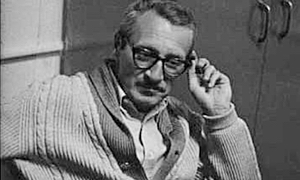

Incomparably Quiet: Bill Evans

There was just something about his playing that said you'd better listen carefully or it would disappear and you will have missed it.

The Vanguard was full and the crowd was noticeably less subdued than usual. They were there to laugh and to hear Lenny kick some establishment ass. They were drinking and being boisterous. And when, about a half-hour before Lenny was supposed to hit, a shy, studious-looking young man in a pale gray suit and tie slipped onto the bandstand, nobody really paid much attention. The whiteness of his face stood out in the shadowy ambiance of the Vanguard.

At first it seemed he might have been there to tune the piano. He studied the keyboard, adjusted the music stand, looked under the hood. When he finally sat down, he hunched over the keyboard and started to play very quietly, almost as if he were testing the piano. The crowd kept on being loud. Nobody paid much attention. Gradually, snatches of familiar melodies started to seep out into the atmosphere. "Funny Valentine. "Tenderly. And that corny old love song, "Young and Foolish, played with heart-rending sincerity for anyone who could hear. Sheer beauty.

I found myself straining to listen over the crowd noise. He segued into a medium tempo "Minority, and I began to notice how his left hand seemed to be finding the sounds between the notes—sounds that resonated not just with your ear but with your brain and your heart. The melody lines he created were full of tiny, subtle tensions and shimmering releases. And it became at times like a choir singing, very softly somewhere in the cellar of a church. Four and eight-bar phrases emerged that could have become whole songs.

The music went softly out into the room and there were pauses in the conversations. Then voices lowered. Then people were looking over at the bandstand, focusing on this frail looking guy with the pale face and the lank hair. The pianist never looked up or seemed to notice. He sank deeper into his singing melodies and now the entire room was listening intently. Glasses stopped clinking. Even the cash register went silent. Somebody had the good sense to lower the house lights. Now we were really all in this together, listening in the darkness to young Bill Evans. People exchanged glances but no one seemed to know what to say. There was just something about his playing that said you'd better listen carefully—or it would disappear and you will have missed it.

Evans finished his solo set with a version of "Autumn Leaves that took the old standard places I'd never dreamed it could go, but where it seemed to have always belonged.

He looked up at the audience for the first time—surprised, realizing that he actually had an audience. He seemed ill at ease. Somebody close to the piano started to clap and the rest of the people joined in. It wasn't the kind of cheerleading, yelling, "yeah, baby! kind of applause that Lenny Bruce would evoke a bit later. It was sincere and reverent and in keeping with what we had all just heard, just witnessed. The beginning of something too new to invite easy description.

< Previous

Reflections

Next >

The Pleasure Dome

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.