Home » Jazz Articles » Book Excerpts » Concepts of Pain: The Stuff of the Sixties

Concepts of Pain: The Stuff of the Sixties

It is said that the '60s ended in 1974, with Richard Nixon's resignation. On the one hand, there was nothing left to believe in. On the other, there was nothing left to protest. Early in the decade, Timothy Leary preached acid politics, thinking that Mao and John F. Kennedy should be sitting in a conference room tripping on LSD, and all the problems of the world would be solved. As it happened, it was Mao and Nixon who finally met, and they just had too much in common. They were stars, beneficiaries of the very liberal rock ethos that promised a life of unbridled freedom for those who opened up freedom for others. It certainly appeared this way when Nixon visited China. A staunch rightwing conservative was appealing to the better instincts of communists. This was a way of appealing to the kids as much as anything else, showing he was on their side—the side of wide-eyed idealism. Meanwhile he was plotting to deny John Lennon American citizenship in New York.

When Bob Dylan went electric at Newport in 1965, he had become aware of the complex Embroglios into which an artist gets himself when he positions himself to be the spokesman of a generation. Any act of protest is subject to reprisal, and an artist has to decide if it is worth fighting to the death, or whether his own life is more important, so he can go on preaching. Dylan went on preaching, but became cryptic. This had already started with Bringing it All Back Home (Columbia, 1965), where he realized that to become self-conscious as an artist is the best way to negotiate complex political issues. As much as he created an intense solidarity at Newport, he also created a rift. It is this imbalance that created the greatest explosions of '60s rock.

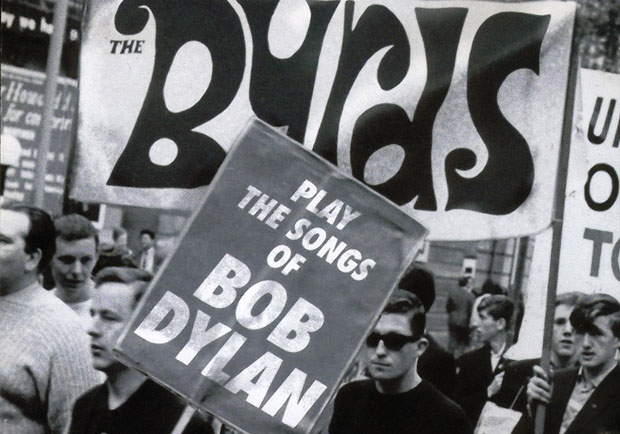

The Byrds understood Dylan even before Dylan did. By mixing their Beatless-flavored jangling sound with Dylan's lyrics, They brought a new quality out of Dylan that was implicit in his surrealist-inspired words, but took a marriage with The Beatles' sound to really start a revolution. The Byrds' sound alternated between a mellow country, almost muzak-like at times, and an insidious psychedelia that often became hardcore. In the end, however intense they got, they always landed on their feet again, all the debris of the wild party cleaned up the next morning. Now, the medium was the message. The radical ideas of the time no longer needed the respectable mantle of traditional folk. What's more, they could be deposited into innocent indulgences of pleasure which, in the long run, are the most revolutionary of all. The Byrds became catalysts of their own catalysts, and although The Beatles' Revolver (Capital, 1966) was the toxin for the psychedelic revolution, they planted the seed.

The American psychedelic acts always had this political edge to their work, derived from Dylan's more openly political early work which ultimately proved their nemesis. In Europe, the tone of pyschedelia was more philosophical and ironic. American psychedelia was largely stopped by hard drugs and the police around 1968. The European version lasted well into the 1970s. That said, it was always the bold confrontations with conventions Stateside that spurred the Europeans ever on, and as a result there is an ultimate oneness to all psychedelia, wherein the later acts complete the story of the earlier ones. Psychedelia goes back to the old country blues singers, and the way they would howl and bend notes on their guitar. It would come to subsume all kinds of unconventional international music, from Indian raga to medieval English songs. In the languid intensities it releases, these histories are implicit, with their own pockets of political reality, microcosms for a new society. Again, after glorious revolution and protest and civil rights in the US, this led to much tragic confrontation; while in Europe, while the music got less attention, it was allowed to grow more organically and evolved into the sounds of the '80s and beyond.

With their electric jug blooping all over the place, The 13th Floor Elevators can be polarizing. Their 1966 debut, The Psychedelic Sounds of The 13th Floor Elevators (Sunspots), is dark, light, spontaneous and desperate all at once. From Texas, singer and leader Roky Erikson had a tough, frontier-like abandon, while at the same time he sang simply and sweetly. Erikson went on to become a martyr for pleading insanity. Busted for pot, he opted for placement in an institute for the criminally insane and received shock treatment that changed him forever. He would go on producing music into the next century, broken though he was, exemplar and mentor to youngsters seeking the flavor of the '60s. Their 1967 follow-up, Easter Everywhere (Sunspots), would step it up a notch, the band riding golden wires of intensity. There is a way to look at Erikson as a call to action, so no one is ever treated that way again. That is indeed part of the message. But the message changes. As we come to explore the conflict through Erikson's own music, we see the primordial beauty there, and realize that he achieved this, and this was a glory in itself to transcend whatever the future was to bring him.

Faust was a German band organized in 1971 by producer Uwi Nettelbeck. In the atmosphere of anomy while the memory of the holocaust was still fresh, Faust's music is fragmentary, featuring bursts like something out of The Beatles' "I Am the Walrus," with shocking onslaughts out of Stockhausen and jazz. "It's a Rainy Day, Sunshine Girl" is simple and typical. The lyrics consist of two lines—"It's a rainy day, sunshine baby. It's a rainy day, sunshine girl"—breaking precedent with sense, forgetting the past, discombobulating the present for a better future. Other works were more serious, and became haunting. Faust never made much of a splash in the commercial world, but they have become legends. It would not do to call them pioneers, though in a way they are. Their abrasive style laid down the template for later industrial music, but their greatness lay in their role as transmitter; they were on the outside looking in. First students of the stumbling of their fathers, they could see the complexities of the American political situation, and knew it took some humor and psychic absurdity to set things straight on the global scene.

The psychedelic revolution spread everywhere, from Latin America to Thailand and Japan. Young bands found a fusion, or a continuum, between the uneasiness of their position in the world, embracing yet shedding folk traditions. Psychedelic rock showed a way of crossing these currents with the ones drifting over from the American counterculture. Tropicalia in Brazil was one such movement, bringing together indigenous music with the wildness of Jimi Hendrix. The electric guitar was shocking in such a state, and even the left resisted it at first, seeing it as a sign of American encroachment. The Tropicalia movement, featuring such artists as Gal Costa, Gilberto Gil and Os Mutantes, went on to enrich the hippie atmosphere they brought into their culture with the type of native folk sounds that complemented them artistically, philosophically and politically. Singers embraced direct targets at the establishment and paid the price. Again, we can look at this as a tragedy, or we can see the songs as new seeds planted in the rain forest, upsetting the cash crops and reestablishing a new equilibrium.

Magma was formed in France in 1970 by mercurial drummer and singer—and radical John Coltrane disciple—Christian Vander. Magma's albums constitute a serial science fiction epic, but in a different language. Supposed to be from the planet Kobiah, this language, Zeul, was invented by Vander and spoken by everyone in his commune, consisting of the many band members. Magma mixed Bach, Coltrane and hippie musicals like Hair to achieve a soaring passion the likes of which have rarely been seen before or since. Vander never explains the words. He says that the music should get the message across itself. The hermetic nature of the group and their habits, whether intentionally or not, provided a kind of solution for the danger many groups of the time got into by being so open politically. The group could go on cogitating in Zeul, tackling the most heated issues of the time, but in a code language protected from the State. And, indeed, the group has stayed together into the first decades of the current century, inspiring a whole cult movement of international underground bands.

England's Pretty Things built the very foundation of 1960s rock. Guitarist Dick Taylor and singer Phil May were originally in a group with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. It was The Rolling Stones' original rhythm guitarist Brian Jones who started the world's longest-lasting band, and Taylor lost out in a fight with him as to who would play that role in the new band. And though Pretty Things had a fairly hardscrabble career, they have inspired as much great rock as their former band mates. S.F. Sorrow (Mississippi) came out in 1967, recorded at Abbey Road at the same time as The Beatles Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (Capital). It is a kind of musical radio drama about the difficult coming of age of an English war child. The music has the same, soaring golden harmonies as The Beatles, and though it is a little rough and tumble, it is a masterpiece and would go on to inspire The Who's Tommy (MCA, 1969). The Pretty Things inspired England with their mutually incompatible gritty, nasty stage presence and their simple, glorious purity. In recent years the band's reunions have been true spectacles, the musicians playing their early work with mature mastery. Again, as the Stones trot themselves out as if in formaldehyde in our time, Pretty Things are still pumping out a vitality and gathering ever new fans.

The '60s are still with us, as they were in the '70s. We are left with a kind of unconscious landscape, on which buildings that seemed solid tumble, and structures that seemed unfinished are redeveloped, or even shown to have a beauty in their unfinished state. Behind these are the nascent ideologies of the '60s, ever-present as the hypostasis of the music. In the '60s culture reached the speed of light. We have been going backwards ever since. But reinvesting in the buried dreams, we become spiritual contractors, making the monuments our own and for our time.

Music is an orchestration of pain, and through pain we reestablish our belief systems. All the slipping out of social conventions, the dislocations—these shared experiences of the '60s youth generation exposed them to a new social nerve center. In The Gay Science (1882) Friedrich Nietzsche lamented that we no longer build for the ages, as in the age of cathedrals. 90 years later, that was still true, but with a difference. Hippies were taking drugs and experimenting with sex, living in the moment as it were. But this is deceptive. Their goals were still long term, establishing civil rights, ending the Vietnam war, creating a more loving society. The pleasures of the moment, by becoming ends in themselves, at once satisfied the instincts on their road to political idealism, and led to a new understanding of human sexual response, extrapolated into a whole new sense of human relations. Much went wrong in the '60s, and that wrong still persists in the form of drugs and crime, but a new understanding of the psyche came with it—or rather the dawning of a new understanding that will take the patience of an age to fulfill.

< Previous

Durga Rising

Next >

Freedom Trane

Comments

Tags

Book Excerpts

Gordon Marshall

United States

John Lennon

Bob Dylan

The Byrds

Beatles

Jimi Hendrix

Gal Costa

Gilberto Gil

Magma

John Coltrane

The Rolling Stones

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.