Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Billy Childs: The Perfect Picture

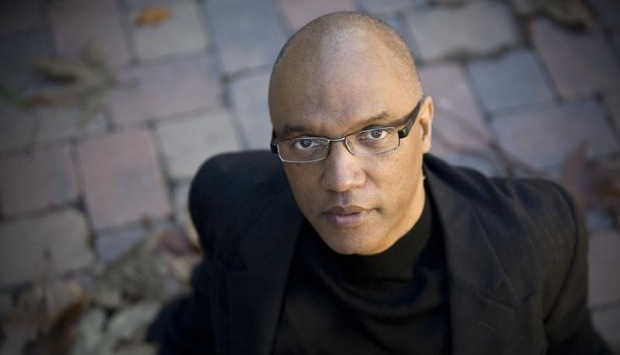

Billy Childs: The Perfect Picture

His Grammy Award-winning Autumn: In Moving Pictures (ArtistShare, 2010) speaks volumes about his stunning attributes as a composer, arranger and musician, while taking us on an unexpected trip around the always- romantic autumn season, with its changing warm colors, quiet, calm landscapes and soft-falling rain. The awarded "The Path Among the Trees" is almost like a prelude to this jazz chamber ensemble experience, perfectly structured around the astonishing idea that music is not about the form, but about the feeling in it. With that in mind, Childs draws a perfect portrait of his very own inner world, where his music is allowed to grow in a controlled environment, provided for this album by the sounds of classically trained dream-makers like the Ying Quartet and harpist Carol Robbins, while reserving a luminous central stage for the jazz elements on it, with drummers Brian Blade and Antonio Sanchez, guitarist Larry Koonse and bassist Scott Colley. The combination is breathtaking.

Childs' piano playing is never exuberant, for that perhaps would destroy the delicate atmosphere of this project. Instead, it is deliciously exquisite and yet filled with a kind of energy only found in musicians whose soul seems to be made out of a certain understanding of this world—where they try to create music that moves and enriches the spirit, and where they know that being human is not a handicap but rather a lesson learned. His musicianship at this point is beyond compare.

This is a jazz pianist who can view the world around him with a classical point of view whenever he wants to, and yet keep those improvised notes coming at will. This earth may now continue its routine circling around the sun, while we get a chance to experience what it would feel like to touch the stars.

All About Jazz: What exactly is The Billy Childs Ensemble?

Billy Childs: I also call it The Jazz Chamber Ensemble. The nucleus of it is six pieces: piano, bass, drums, acoustic guitar, harp and sax, and then sometimes I'll add a string quartet, and sometimes I'll even add something else on top of that, like a wind quartet. But the nucleus is all six pieces, and an even smaller nucleus, like piano, harp and guitar, which is kind of the sound that led to the whole thing to begin with.

AAJ: Are there any boundaries for you between jazz and classical music?

BC: I don't think there are, or there are less than one would think. I look at music kinda like I look at religion, where you have great religious leaders for every different religion, and the higher you get, to their level, you discover that a lot of them are talking about similar things—like treating everybody like you would treat yourself; they talk about love. And the lower down you get, that is where you start getting all these different separations. And I feel the same way about music: the higher up you get in your spiritual awareness of music the less the boundaries are, and the less developed you are, the more you are ruled by those boundaries. If you are in a spaceship and you look at the Earth, if you see America you don't see the actual shape that is supposed to be, as dictated by the boundaries that we have made. You just see land. That is the way I look at it.

AAJ: Do you think the conception of jazz has changed, from the classical point of view?

AAJ: Do you think the conception of jazz has changed, from the classical point of view? BC: You mean like a condescending attitude towards jazz, because they don't have the so-called necessary training that classical musicians claim that is necessary? Yes, I think there is a lot of respect. I am in my fifties, so when I was like fourteen and I was impressionable and my conception of things was pretty much being formulated, that was when fusion was happening, in the early '70s. The point is, that that era was kinda like an unprecedented era between genres: respect and tolerance. So for me, that separation between genres was broken down during that era. Nowadays, a lot of classical musicians want to know how to improvise; they can see the importance of jazz. And there is also an attitude in jazz musicians towards classical musicians that thought that the latter were stiff, inflexible and soulless, and that is not true either.

So a lot of jazz music, like mine and other people's, has a lot of classical form in it. I don't even call mine jazz; I call it jazz chamber music. But nevertheless a lot of jazz musicians use a lot of long forms, a lot of heavy composition, and a lot of classical musicians improvise, so there is a desire to connect.

AAJ: The Ying Quartet.

AAJ: The Ying Quartet. BC: Well, you know, actually it's changed, because the first violinist, Timothy Ying, left. He stopped doing music all together, so I guess he's a lot happier. But he gave me the honor of making my project his last project, and they had been working with that string quartet for almost 20 years. I met the violist, Phillip Ying, in New York. There is this organization there called Chamber Music America, and he was the president at the time, and they asked me to be on the board, and I joined, and then I met him. And we did this project together; we hit it off really well. In fact, we did "The Path Among the Trees;" that was the first project that I did with him. It started out as a commission.

AAJ: Tell us about the journey of Autumn: In Moving Pictures .

BC: I should start with "The Path Among The Trees." I live in Southern California, and we don't really have any seasonal changes. So, when one autumn I went to upstate New York—I was doing a tour in 2007—I was just blown away by how beautiful the autumn was there, with all different color leaves on the trees. I describe it on the liner notes. As I was driving down I-95, there was this little pathway that I saw in the midst of all this, with a profusion of color—with green and red and brown and amber, all of these colors on this path among the trees. And I was thinking what would it be like to tell a story about some journey along that path: where would that path lead you? So I started thinking about what the music sounds like, coming down that path, and I came up with that piano that opens the piece, and from there the piece evolved, which a lot of times that is the way it goes for me.

With "Waltz for Debbie," I was a little worried about this arrangement, because I know that the song that Bill [Evans] wrote is about innocence—about his niece Debbie, that I think was eight at the time—and is a beautiful song. It almost sounds like a music box playing, when it first starts out. It is beautiful and very delicate. And I kinda take the song through the wringer ... and I don't know why I did that. [Laughs.] Actually, it kinda met a lot of different things that came to be in place. One was that, where I grew up, one of my parents' favorite groups to listen to were The Swingle Singers, that would sing a cappella classical compositions, and would have a rhythm section playing really jazzy behind them, too. And that used to turn me on as a kid; I used to love them. So what's a slow moving melody that could go over that kind of concept? And I kept coming back to "Waltz for Debbie." So that was kinda like the initial idea. And structurally I was thinking—and this was really strange—that it could have, like, a vortex that seems to speed up, almost like a dark hole, and then it comes back on the other side, and you play the melody again, but now it's like an ultimate reality of the melody. That's kinda like the story line behind it. Debbie turned into a complicated young woman; she is no longer innocent. The harp intro and the piano conclusion at the very end are sort of a reminder of the innocence of the song.

In regards to "Prelude in E Minor," well, on my album Lyric (Lunacy Music, 2005), I do a "Prelude in B Flat Major," which is the same orchestration: piano, guitar, harp and bass—no drums and no sax. And if I keep doing these series, I want to write a prelude for each one. I kinda got the idea from Bach. So I would like to do that. And the language of each key is this baroque language, but it is a little bit more modern. The middle part of the prelude is actually very directly influenced by Ravel a lot. I treat this piece like an interlude, like a resting point in the middle of the CD, because what's around it is very intense. You have "The Path Among The Trees," which is a 13-minute piece where you have all these peaks and valleys, and then you have "Waltz for Debbie," where you have a very adventurous treatment of this song, and then the prelude, followed by another long, ambitious piece, "A Man Chasing the Horizon." So it's like a resting place in the storyline of the CD.

"A Man Chasing the Horizon" is structurally held together in a tenuous way. The transitions are not smooth: they abruptly stop and start. They are loosely tied together thematically; I'll take one theme and throw it in this other section, as to remind you that we are listening to a one long piece. Like, for instance, the piano solo is more like a conversation between three people, and that just happened that way because of how Scott [Colley] started. I wanted him to start with a bass line that I had written, but he started with something else, which turned out to be so much better than what I had written, and eventually it turned into the section that I had written. It's a lot of virtuosic playing. And the Ying Quartet is very involved. I wanted to try and do something I had never done before—which was my love for Stravinsky and Bartok—and really involving a string quartet writing, because I wanted to somehow apply that to a jazz context, where you have drum set, and piano and guitar playing along with it. So I kinda used the string quartet as the centerpiece and wrote everything around that; that was pretty much where it was coming from, conceptually. It tells the story of futility, about a guy who is going through all kinds of things to chase something that's unattainable, like a horizon. The title comes from a poem by Stephen Crane, "I Saw a Man Pursuing the Horizon."

"Pavane," by Fauré, is one of the most perfect melodies ever written, to me. There is not a note or a harmony that needs to be changed in that piece, so what I did was just kind of modernized the harmony and orchestrated it, but I wanted it to sound warm. I wanted it to create the sound of air in this melody. I wanted to leave the air sound of this melody untouched and un-messed with, and I did it as beautifully and as lovingly as I could. So the melody remained intact, but it still has my stamp on it. Actually, I changed the structure, because it was going to be like a straight-ahead jazz ballad, and what I did was just play the melody on the piano. You don't have to improvise or anything; the melody is strong by itself, with a really nice, warm touch, and that would be enough. So there is no improvisation on that song; it is just like a classical piece. I played it with my own voicing on the piano, but it wasn't like any jazz improvisation.

On that drive I mentioned on I-95, one of those days it started to rain. You know how sometimes the sky is blue over here and it is raining over there? Well, it happened to be raining on us. And the patterns of the raindrops on the windshield, as we were driving down the road looking at that beautiful landscape, were hitting the windshield in certain rhythms and certain patterns, and I was sitting there thinking about the rain. It really appeals to me. A nice gentle rain that is raining on these leaves—the sound of them hitting the earth, the windshield or the streets—is something that is beautiful to me, and I wanted to write a piece that represented that, and the piano pattern is what sparks it off. It is sort of glued together by the piano, but there are no landmarks, in terms that you can't hear where the time is, it just sounds like notes that keep happening. It is not a definite pulse; it just keeps flowing, like water falling. So the piano glues everything together, and the instruments come in and out at different times, make their statement, and then they leave again, and that is the spirit of that piece, because that was how the rain was making that impression on me, with shifting rhythms.

There was a constant, steady sound, but it would change slightly, so that was kind of the story I am telling there. At the end, it is reminiscing rain and then sounds that are supposed to sound like drops of rain. This one was one of the most difficult ones to assemble, because there are no landmarks. If you were driving and had no landmarks, you wouldn't know where to turn. In this music there is very few—it just keeps going and you have to keep counting in a very focused and concentrated way, otherwise you get lost, and if you miss your spot ... It is like a fabric: everybody's part depends upon everyone else's for the success of the song. One that misses their entrance or gets in a bit early or a bit late, then it blows the whole thing off, it derails the whole thing. All of my music is like that. So it took a lot of rehearsal to finally get it. It's one of our favorites.

There was a constant, steady sound, but it would change slightly, so that was kind of the story I am telling there. At the end, it is reminiscing rain and then sounds that are supposed to sound like drops of rain. This one was one of the most difficult ones to assemble, because there are no landmarks. If you were driving and had no landmarks, you wouldn't know where to turn. In this music there is very few—it just keeps going and you have to keep counting in a very focused and concentrated way, otherwise you get lost, and if you miss your spot ... It is like a fabric: everybody's part depends upon everyone else's for the success of the song. One that misses their entrance or gets in a bit early or a bit late, then it blows the whole thing off, it derails the whole thing. All of my music is like that. So it took a lot of rehearsal to finally get it. It's one of our favorites. And finally "The Red Wheelbarrow," inspired on that poem by William Carlos Williams, found on the liner notes of this CD. If you didn't know the poem or where it came from, you could go, "How does this song sound like a wheelbarrow?" Because a wheelbarrow is a very functional, mundane object; so how is that translated into something beautiful? But after you read the poem, then you understand. The story I heard is that Williams, who was a doctor as well, was treating this young girl, and it wasn't looking very good. And for some reason there was a red wheelbarrow outside the window, and he was looking at it, and he thought so much depended on it; for some reason he saw the whole balance of the world focused on that object. It represented the delicate balance of everything and everything's dependency on everything else. When I read that poem, I think of a lonely red wheelbarrow in the middle of an open meadow, and it just rained, and the wheelbarrow has water on it, and you see this beautiful landscape. It is almost like an impressionist painting of still-life objects. I am playing very simple chords, and pretty much the guitar is telling the story of this red wheelbarrow. If you can imagine these trees that are around, there is an open field, there is grass, and everything is serene and still, and it just rained and there is this red wheelbarrow. And that is kind of the picture of autumn in my mind as well. And Larry [Koonse] plays it so beautifully.

AAJ: This is a very beautiful and deep record.

AAJ: This is a very beautiful and deep record. BC: Thank you. I make a distinction between active listening and passive listening, and my music is for people who engage in active listening. In other words, you listen, but you interact with the music. It is becoming like a thing of the past almost, a lost art, to be able to listen to music and have it bring images to your mind. A lot of times it seems to now be made to lure you into a stupor or to make you move your body or shake your booty. So what I try to do with music is like going to a movie: Images that stimulate you, that make you interact with it and become your reality. The liner notes were written to explain to people that this is the direction that I was hoping to take you in with this music. This is my version of it, because everybody's reality about everything is different.

What is a beautiful autumn scenario to you is going to be different than what is a beautiful autumn to me, because you have what's going on in your mind based on your own experiences. But that's what the music is for, to be able to connect your experiences with mine, and I think that is what music should do. So that is hopefully what I did with this album. And I always thought that. Hopefully when you listen to it, you find something new. Melody and rhythm speak to people. So I feel that you need to have a beautiful melody that invites people in, because I always like to make music that invites people in. I don't want it to alienate people, or to be so complex and inaccessible that they can't even relate. And I always feel that melody is a way, like a portal, to enter people's soul. But I feel that, once you write a solid melody that people can hear, then you can get as complex and as layered as you want underneath it, because people will trust you that it will be something they can relate to, and it makes logical sense to them because they can relate to the melody that you wrote. So that's kind of where I am coming from.

AAJ: What word would you choose to describe this whole project?

BC: Healing, because that's what I am trying to do. I think the world is really messed up; there are a lot of messed-up things. So the only thing I can do is to try to create things and bring things into the world that I see as beautiful, and hopefully that will have a healing effect on a lot of things.

AAJ: Is there a difference between you as a composer and you as a pianist?

BC: Yes. Although when I improvise, I try to be as structured and spiritual as possible and do things that make sense; and when I compose, I try to make things sound spontaneous, happening in the moment, that are not pre-planned. I think of myself as a composer-pianist rather than a pianist-composer. I have a degree in composition and I studied composition with some of the best teachers ever, and I took lessons of piano, but most of my training with the piano came from just gigs. So there is a different methodology of learning two different crafts.

AAJ: And then there is also the arranger.

BC: Yes. [Laughs.] I will do an arranging assignment if something is really interesting to me—like Dianne Reeves' The Calling (Blue Note, 2001). That is like my favorite arrangement assignment that I have ever done in my life. It was a treatment of songs that Sarah Vaughan did. Dianne and I are about the same age and come from the same school of thought, where music should have ambition and music should have a vision. In the '80s, music lost its ambition and became this minimalism, repetitive type of disco BS. Dianne and I came from the school of thought where the music should have ambition—it should try to change things and revolutionize things. That was kind of the position we took with the CD. The arrangements were more interactive, and they interacted with her vocals, and were not only made for her to sing over them. It was a really great experience.

She really exhibited a lot of trust in me, and I will never be able to repay her for that. It put me on the map for arrangement. Most of those jobs are about artists that want their vision with your skills. A lot of people are cool with that, but I am not, because I have my own vision too. Many people have very specific visions in their head about how the concept of an album should go, and that is fine. But I want to arrange for people whose vision is very similar to mine. And my vision had to do with how the music makes us grow as humans: how does it further create that critical thought, how can it move forward. And if I am working with an artist that has that kind of impact, then I am cool with working with him or her. But if it is an artist that just wants to sell records or: "I would like to be adventurous, but the fans may alienate me," then I am not interested in arranging for something like that.

AAJ: The so-called fans should be about the growth of the artists anyway.

BC: Yes, it should be, and that is how it used to be. Because just look at the music industry. Like, for instance, we can all agree that the record industry was greedy, charging people 20 dollars per CD, and they would get one song per CD that was any good. And it cost them like five dollars to make that CD. So people started getting tired of that. Then here came the downloads, and it changed the whole public perception of things in relationship to music. And now people, especially younger people, think that music is an entitlement and that it should be for free. They also have things like iTunes playlists that have 20,000 songs, with songs they don't even care about, so consequently this relationship between the fan and the artist is completely gone, because—and this is speaking about what you were talking about— now there is no relationship between artist and fan. When I was like 20 and somebody was coming out with a CD, it was like an event. You were waiting: "This person is going to come out with this CD, and I am going to go and buy the CD because I have been following their music." That is gone.

BC: Yes, it should be, and that is how it used to be. Because just look at the music industry. Like, for instance, we can all agree that the record industry was greedy, charging people 20 dollars per CD, and they would get one song per CD that was any good. And it cost them like five dollars to make that CD. So people started getting tired of that. Then here came the downloads, and it changed the whole public perception of things in relationship to music. And now people, especially younger people, think that music is an entitlement and that it should be for free. They also have things like iTunes playlists that have 20,000 songs, with songs they don't even care about, so consequently this relationship between the fan and the artist is completely gone, because—and this is speaking about what you were talking about— now there is no relationship between artist and fan. When I was like 20 and somebody was coming out with a CD, it was like an event. You were waiting: "This person is going to come out with this CD, and I am going to go and buy the CD because I have been following their music." That is gone. Now you have these computer programs, and now it's become, like, "I don't care who did it. I just want this song." It is moving towards independence, where artists will have to cultivate their own relationships. Artists will have to take an active attitude. Because as long as we remain human beings there's always going to be a need for a self-expression and relating to someone expressing themselves. As long as we are humans, we have to have creativity. It can't be stopped by computers; this is changing. The art has to be more intrepid and more vigilant.

AAJ: Well, some still like to have the CD in their hands, to read the liner notes, find out who played, who produced, who wrote the songs—and even who the sound engineer was. And they are not so thrilled about downloads.

BC: Yes. That's exceptional. ... Maybe you are right at the edge of this transition of how things used to be. You are like one of the rare exceptions.

AAJ: Please tell us a little bit about that first recording in 1977 with Janice "Ms. JJ" Johnson.

BC: Oh, yes. I was 19 at the time when I got the call. I met this guy, Kevin Johnson, a drummer, and we hit it off immediately. We became best friends. I went over to his house—for a couple of years—every day, talking about music and that kind of stuff, and finally he said, "You know, my dad wants to take a group to Japan. do you want to go?" and I was, like, "Oh, okay." I had no idea his dad was JJ Johnson. So I went over to his house to rehearse, and it was JJ Johnson, so I almost had a heart attack! That's how I ended up there. You have to understand that I was a student at USC, a sophomore, and basically a "nobody," and I dressed like a clown. I had no regards for my appearance. Studying music was my whole existence.

So I was kinda like this invisible person on the campus of USC. I got some new clothes to go to Japan because we were going to do some concerts, and I stepped off the plane and immediately some Japanese people were coming on to me and taking pictures and asking for my autograph, and they are handing me programs with my picture in it like I'm a star; it was like a cultural shock! So we get off the plane, and we do a TV show immediately, and then that night I went to the hotel and saw myself on TV. So to a 19-year old guy, that was 1977, that was almost nerve wracking, which was great. We were there for like two weeks. We did the Yokohama concert—that CD. It was fun. I'll never forget it. I'm missing JJ.

AAJ: Freddie Hubbard.

BC: Well, Freddie Hubbard is the reason, in large part, why I am talking to you now. I regard him as a teacher and a mentor and a friend, and someone who gave me something that the only way I can repay him for what he's done for me is to do the same for someone else. He hired me and allowed me to learn from his genius, which is a rare gift. And he was, as we all know, a very flawed individual, but he had a huge heart; his soul was intact. There were a lot of times when I had no business on stage with him. I mean, he was so great and I was still learning; it was like I shouldn't even have been up there. But he was there trying a solo, and would tolerate my youthful coping decisions until he couldn't stand it anymore, sometimes, and he would just turn around and say, "Lay out." But still, he taught me what I should be doing, and he was never mean or abusive to me, and he was always nurturing and always, always genuinely interested in my development. To me he is like a hero.

AAJ: Tell us about the 2009 Guggenheim Fellowship Music Composition Award. It is a pretty big deal.

BC: In 2009, I applied for a Guggenheim Fellowship, and I won it. I was surprised. It is a big award. Chris Botti compared it to a Nobel Peace Prize, but I don't think so. [Laughs.] ... This is an award for a really, really great musical career, but, that being said, I was honored to get it. I applied for it and essentially it paid a large part for Autumn: In Moving Pictures. I think maybe a hundred people win it every year in all the different facets of the arts, but there are, like, tens of thousands of applicants, so it's a very select few—a very privileged honor. You can keep re-applying every year, and there are people who have been applying for it for, like, 20 years. I got it on my first try, so that was really an honor. So, it's an acknowledgment of your artistic importance in the scene of American Music; so it's quite an honor.

AAJ: Well, music is basically food for the soul, so maybe it is still okay to compare it with a Nobel Peace Prize after all.

BC: I think you are quite right— music is very necessary. To me, there are certain basic human needs: there's the need for food, for love, for water, for companionship, and then just as important as these needs, there is the need for self expression—to be able to say what is on your mind to someone who will listen to it. And that takes a lot of forms. Dancing, drawing ... even violence! Music is a form of expression, as well, that is crucial to our existence on this earth. I try not to look at myself as too important, so that's why I kind of feel a little uncomfortable with [it] being compared with a Nobel Peace Prize. I think that if you start viewing yourself as way important, you lose something.

BC: I think you are quite right— music is very necessary. To me, there are certain basic human needs: there's the need for food, for love, for water, for companionship, and then just as important as these needs, there is the need for self expression—to be able to say what is on your mind to someone who will listen to it. And that takes a lot of forms. Dancing, drawing ... even violence! Music is a form of expression, as well, that is crucial to our existence on this earth. I try not to look at myself as too important, so that's why I kind of feel a little uncomfortable with [it] being compared with a Nobel Peace Prize. I think that if you start viewing yourself as way important, you lose something. AAJ: You also have two Grammy Awards, both in 2006: Best Instrumental Composition and Best Arrangement.

BC: That was a very good year. I won for "Into the Light," which was also on Lyric, and for a collaborative arrangement on a Chris Botti CD [To Love Again: The Duets (Sony 2005)] for "What Are You Doing the Rest of Your Life?" with Sting singing. So it was a really huge honor to get a Grammy. It's nice to be recognized by your peers that you do something well.

AAJ: Your 2011 Grammy for "The Path Among The Trees," from Autumn: In Moving Pictures.

BC: Well, I won the Grammy for Best Instrumental Composition—"The Path Among The Trees." It's my third Grammy Award, and my 10th nomination, and my second for Best Instrumental Composition. This year, in 2011, I was nominated in two categories: Best Instrumental Composition and Best Large Jazz Ensemble Album—Mingus Big Band won that one. After I won, I got to hang with Herbie Hancock and Vince Mendoza, and we all went to the press room.

My nominations were two of six nominations for Artistshare artists this year; I was the only winner. Hopefully, Volume 3—whenever it comes out—will be acknowledged in the same way that Volumes 1 and 2 have been. It's been a great ride so far.

AAJ: What's the best thing you think you've ever done?

BC: Oh man! That was going to be my next statement. Have I told you that? It's weird that you would ask me that. It was right on my mind. The best thing that I have ever done, musically, ever, was a piece that I wrote, and it's called "The Voices of Angels," and I wrote it for the LA Master Chorale. It's funny you should ask that. I was just about to answer that question before you even asked me. There is this collection of poetry called "I Never Saw Another Butterfly," and basically it's poetry written by children in this concentration camp called Terezin, in the Czech Republic. It's basically a fortress that was built by this guy in Prussia before it became the Czech Republic, but the Nazis used it as a concentration camp for Jews, so it's kind of a town that's built around this fortress, but the fortress itself was the actual concentration camp, and the town was also occupied by the Nazis.

It was a place where the Nazis would let the Jewish culture thrive because the Nazis wanted to look good in the eyes of the world community, and still were hiding the fact that they were exterminating Jews. So they wanted to give the impression that they were just occupying these ghettos and letting Jews keep their culture. So basically, they would let cultural things happen, and one of the things that they did was to let the children start a newspaper. And in this newspaper there were articles, poetry, drawn pictures. And a lot of this poetry was saved after the war ended, and most of the children did not survive—they died of typhus. I took six of these poems—and they are really heart breaking poems—and I set them to music score for a whole chorus, like 120 voices, a full orchestra, which is like 70 people, and two vocal soloists. And basically what I did was, I took the poetry and I arranged it so that it started from a place of darkness and despair, sadness and anger, and kind of morphed in tone so that the tone will change gradually, so by the end of the piece it was this ecstatic vision of life- affirming poetry.

You know, that is why I compose music—so that my music can be looked at as a gift to humanity. I think that all musicians ultimately want to contribute to humanity, in the sense that our music is something that has a healing effect on our troubled state of affairs. The poems were so powerful that I felt compelled to honor them as closely as I possibly could. I looked at every sentence, at every word in that sentence, and asked myself, "How does it make you feel?" Then I tried to musically describe that feeling, using everything I knew about harmony, melody, rhythm, orchestration, et cetera.

Emotionally, I envisioned my own boys with their hair matted and filthy, with rags on their bodies, their ribs showing, with tears in their eyes, and having seen murders, death, desperation. My boys were twelve and eight at the time when I composed it, so they were at the same age as many of these children. Needless to say, these constant daily visions, while musically motivating, were the source of great stress, depression, and angst. Still, I wouldn't exchange that experience for anything.

I did approach the words as though they were a soundtrack to the lives within the confined walls of Terezin—a soundtrack where a butterfly, with its gently fluttering yellow wings, represents a freedom these doomed children will never know—and has the same emotional weight as ..."30,000 souls who will see their own blood spilled." A soundtrack where ..."the dandelions call to me" and "death wields an icy scythe." The arc of the piece had to be a journey from darkness to light, from despair to hope. That tells the story of the resilience of these beautiful children. I wanted to emphasize that, in spite of all the unnatural shit that they have seen, they remain—as children most often do—optimistic, which requires such superhuman strength! There is a section on one of the poems, "Birdsong," where it says, "Hey, try to open up your heart to beauty; go to the woods someday and weave a wreath of memory there. Then if the tears obscure your way, you'll know how wonderful it is to be alive." It is so simple, powerful, and beautiful, that the music just made itself evident to me immediately. That passage to me is the central idea of the entire piece; it literally brought tears to my eyes as I was composing it.

I did approach the words as though they were a soundtrack to the lives within the confined walls of Terezin—a soundtrack where a butterfly, with its gently fluttering yellow wings, represents a freedom these doomed children will never know—and has the same emotional weight as ..."30,000 souls who will see their own blood spilled." A soundtrack where ..."the dandelions call to me" and "death wields an icy scythe." The arc of the piece had to be a journey from darkness to light, from despair to hope. That tells the story of the resilience of these beautiful children. I wanted to emphasize that, in spite of all the unnatural shit that they have seen, they remain—as children most often do—optimistic, which requires such superhuman strength! There is a section on one of the poems, "Birdsong," where it says, "Hey, try to open up your heart to beauty; go to the woods someday and weave a wreath of memory there. Then if the tears obscure your way, you'll know how wonderful it is to be alive." It is so simple, powerful, and beautiful, that the music just made itself evident to me immediately. That passage to me is the central idea of the entire piece; it literally brought tears to my eyes as I was composing it. I spent a year composing this piece. And when we performed it, we had, like, ten minutes' standing ovation, four curtain calls. ... I had people coming to me crying. ... It was, like, two hours before the last person left after the concert was over. It was the most amazing experience I have ever had.

< Previous

Human Element

Next >

In Search Of ...

Comments

Tags

Billy Childs

Interview

Esther Berlanga-Ryan

United States

Brian Blade

Antonio Sanchez

Larry Koonse

Scott Colley

Dianne Reeves

JJ Johnson

Freddie Hubbard

Chris Botti

Sting

Mingus Big Band

Herbie Hancock

Vince Mendoza

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.