Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Barry Guy: Striving For Absolute Spontaneity

Barry Guy: Striving For Absolute Spontaneity

Guy held a concert with Mats Gustafsson in Lithuania on January 11th, 2009. The short-but-eventful visit was crowned by the glorious performance at St. Kotryna Church. Guy played solo, in duo with Gustafsson, and in a sextet with Gustafsson and Lithuanian musicians Liudas Mockūnas (reeds), Skirmantas Sasnauskas (trombone), Eugenijus Kanevicius (bass) and Arkadij Gotesman (drums). The performance was released by the new label NoBusiness Records on a limited-edition LP, Sinners, Rather Than Saints.

All About Jazz: Barry, you are a rare example of a musician who feels equally at home in classical (baroque) and so called "new music." Is classical training useful or even essential for an improviser?

Barry Guy: Perhaps [I'm] an unusual case of being a musician equally at home in baroque, classical, contemporary and improvised musics. As such, I feel fortunate and I enjoy the disciplines that each offers, but of course this situation is not for everybody, and indeed not every musician has had a good fortune to receive such a rich musical education.

So your question concerning the usefulness of classical training for improvisers is somewhat speculative, in the sense that many musicians have thrilled us with their music without a classical foundation. In my case, I think it has helped because a sound technique has allowed the analytical and creative aspects to operate unhindered by technical restrictions. Having said that, none of us is foolproof, so there is always the mountain to climb. Expanding and refining one's language is the driver for continuity. Each of us has to find our own direction according to what we have been given or what we find.

AAJ: How would you describe your music in terms of style? Who do you consider your predecessors or greatest inspirations?

BG: Within creative music, I've never thought of "style" as such. My musical vocabulary is built upon my contacts with like-minded players and composers. I inhabit musical areas loosely known as free jazz, improvised music, new music—all inadequate terms to describe a vast variety of musical communication—and for me, the word "communication" represents the focus of my endeavors.

Inspiration has come from many quarters and this should not to be thought of as plagiarism. Inspiration for me implies lessons that open up channels of thought, and ultimately testing the hypothesis. Monteverdi, Bach, Beethoven, Biber, Xenakis, Bartok, Shostakovich and Mingus are composers that have inspired me with their sonic architecture. And what an important last word that is—the structure of music, buildings, paintings and text all offer us ideas which challenge us to dig deep into ourselves.

Most bassists of my generation have huge respect for Gary Peacock and Scott LaFaro—two players that redefined what pizzicato was all about. But you know, we cannot play like them—they are unique. But what we learn are the possibilities that are open to us. We take on the idea of space, fluency, construction, but not the pitches—these are special to those people. I am inspired by Charles Mingus for his daring to break away from routine models and create passion in his music. Now my greatest inspiration comes from the musicians that I make music with—it's an ongoing love affair.

AAJ: Is there a fundamental difference when composing music for big orchestras, small groups and solo performance?

BG: Well, firstly and obviously, there are different degrees of scale in terms of the ensemble size. The art of composition assesses each situation and proposes a structure appropriate to the formation and, importantly, the players. The thorough composed input has to be balanced with the improvisational goals, so it is safe to say that the larger ensemble generally demands more organization, unless of course the group plays without composed elements, which is equally valid. My goal has always been to provide music that engages the players and allows the individual maximum freedom within the context of defined material.

AAJ: What are the basic principles behind an improvising orchestra (or the set of musicians/instruments)?

BG: As far as I am aware, there are no basic principles concerning the instrumentation—it is purely a matter for the organizer or the collective to decide who plays. My preference was for an orchestra that approximated existing or historical big bands, mainly because I had an interest in writing for a "Classical" well- tried format but changing the way in which the ensemble was used.

AAJ: How did you come up with an idea to put together a big orchestra? How was the London Jazz Composers Orchestra born?

BG: The LJCO was formed because of my desire to celebrate the picturesque musical life I was leading at the beginning of the '70s in England. I brought together lots of the musicians I had been working with across a fairly wide spectrum of improvised music. And, to make some sense of this powerhouse of creativity, I envisaged an extended composition that moved and flexed with the improvisers' aspirations. The extended composition was called "ODE," consisting of seven sections that would feature all of the musicians of the LJCO in one scenario or another. My composition professor at the Guildhall School of Music, Buxton Orr, conducted the first performance and continued to direct for about 10 years after that. The excitement of the final result filled me with energy and enthusiasm to embark upon other projects.

The realization of "ODE" was difficult and often contentious, with many musicians having to deal with time/space notation, plus improvising. The fact that we got a recording made me realize that the human spirit is indeed resilient.

AAJ: London Jazz Composers Orchestra—why "jazz" and why "composers"?

BG: You will recall that there existed the Jazz Composers Orchestra in the U.S. in the late '60s/'70s. Michael Mantler wrote some original scores, which interested me because my own writing method accorded with his presentation of the music—basically a time/space notation. In a rather naive way, I hoped that there would be a future collaboration between large ensembles, so I called my formation the London Jazz Composers Orchestra to honor the existence of the American counterpart. The name seemed appropriate because the orchestra was made up of jazz/improvising musicians, and composition represented the structural spine. Over the years of LJCO existence, the amount of composed material varied greatly, which was as I had hoped. No rules were laid down, although I guided the ensemble towards a format of composition and improvisation rather than a totally improvised format.

AAJ: You have mentioned "time/space notation" a couple of times. Could you to tell us about that in more detail?

BG: This way of notating music allows a certain flexibility in the delivery of musical information. Simply put, measures or bars can be fixed by chronological time rather than metronomic beats, and within this time period [space] events can be delineated. These events can take on more precise articulations or can be improvisational. Imagine the goal posts in football. Between these vertical posts, the player can judge where the football should land—just inside, towards the center, perhaps central. The music can be visually laid out to suggest the positioning of a note or phrase within the external limits of the bar lines or goal posts.

BG: This way of notating music allows a certain flexibility in the delivery of musical information. Simply put, measures or bars can be fixed by chronological time rather than metronomic beats, and within this time period [space] events can be delineated. These events can take on more precise articulations or can be improvisational. Imagine the goal posts in football. Between these vertical posts, the player can judge where the football should land—just inside, towards the center, perhaps central. The music can be visually laid out to suggest the positioning of a note or phrase within the external limits of the bar lines or goal posts. Time/space notation appears in many forms—each composer having a different objective. It just happens that a certain freedom away from the "tyranny of the bar line" occurs and is particularly suited to music that has improvised elements.

For its relevancy to the discussion, Guy gave us permission to excerpt from the article "Freedom In Restraint," by Kees Stevens, in the interest of highlighting some of the goals behind the LJCO.

"There are three periods to distinguish in the 25 year-old history of the LJCO. At the beginning the music scores were very detailed. They also worked with a conductor, Buxton Orr, Guy's composition teacher. Due to the constant refinement on the compositional side and radical abstraction, Guy alienated musicians from himself. For example Bailey left the orchestra because he absolutely could not feel at home with such an approach. In the second period he invited his fellow musicians to write pieces for the orchestra. Kenny Wheeler, Paul Rutherford, Howard Riley and Tony Oxley delivered contributions. The orchestra also played a piece by conductor Orr, whilst in the repertoire of that period there was also a piece which Penderecki had written for the Globe Unity Orchestra. That repertoire offered a broad spectrum of complete, written scores, through the looser ones from Rutherford to the more graphic ones of Tony Oxley. Furthermore, the "orchestra's composers" saw the business from the other side.

The decision to drop the conductor marked the third phase of the orchestra. According to Guy an orchestra with a conductor causes you to write for an orchestra with a conductor, and he wanted to get away from that. He advocated a looser approach, in which a few directions are sufficient and the musicians are responsible for taking initiative. He was very aware that a working method of that sort could not be achieved in a few years, but the construction of the orchestra has barely changed in the last ten years, so that everybody knows what they can expect from each other. There are still meticulously notated passages. That's how he, for example, will work out riffs, but in contrast to the orchestra's first period, the result heard is more supple, more natural."

AAJ: Please tell us about balance between composition and improvisation in your music, particularly for bigger ensembles. Do you think there can exist an ideal ratio between the two approaches?

BG: I work hard at imagining how improvisation and composition can coexist together. I try to reinvent the wheel when a new piece is envisaged, since all circumstances are different. So there is no immediate solution nor any ideal ratio or balance that can be replicated. Every large ensemble piece poses new problems—not unlike designing a house for a client. I take on board the various parameters and doggedly work away, until a sense of structure emerges that best reflects the aspirations of the ensemble. The musicians come first.

AAJ: What other orchestras work in the same genre as LJCO?

BG: Every large ensemble is guided by its players and composers. I have my own methods, which will be different from others. So it is difficult to speak about the same genre except to say that any searching orchestra will have similar objectives, and that is to provide a platform for the improvisers' art.

AAJ: Large jazz orchestras seem to be a rare phenomenon these days. Is it mainly because of economic factors?

BG: Economic factors obviously play an important role in the continuity of any large ensemble. The big band era, as such, is long past, but it has in fact been quite heartening that musicians have got together and continue to do so to research and perform large group music. Concerts are infrequent, but most countries possess a few lively spirits that allow the medium to survive. The technical facility of many young players and their awareness of musical genres has been gratifying. There is a future for improvised music in the large ensemble, I think.

Barry Guy with Lithuanian Musicians

Barry Guy with Lithuanian MusiciansAAJ: Please tell us about freedom in free music. As a composer, what do you think about striving for absolute spontaneity?

BG: I am a composer and an improviser that can operate with the most rigorous written music and the totally free context. Being creative is my main objective, and being aware of one's colleagues active in the art of playing music is a priority. Hopefully, spontaneity will result from a lot of performing and a discipline behind the endeavors. Absolute spontaneity? I can only say that we must always be ready to react.

AAJ: Can "non-idiomatic improvisation"—proposed by Derek Bailey—still be called music?

BG: I have never understood "non-idiomatic music" as proposed by Derek Bailey. One definition of idiomatic is "characteristic of a particular language," and as far as I can understand it, improvisers are involved in a language, a communication. There are, of course, different dialects, not all compatible, but nevertheless there exists a potential for understanding. An idiom is a form of expression peculiar to a language, person or group of people, so to think that successful music can be made by abandoning the core principles seems to me somewhat dilettantish.

Derek's phrase has been often quoted as a revolutionary principle. In fact, I think it was thrown in to the improvising arena as a taunt to musicians who abided by a set of principles that included continuity and self-development in their individual practices. The phrase also, to my mind, represented a contradiction, since Derek himself continued to develop quite systematically his playing methods. Idiomatic, even...

Derek's phrase has been often quoted as a revolutionary principle. In fact, I think it was thrown in to the improvising arena as a taunt to musicians who abided by a set of principles that included continuity and self-development in their individual practices. The phrase also, to my mind, represented a contradiction, since Derek himself continued to develop quite systematically his playing methods. Idiomatic, even... AAJ: Composed or written music is often perceived as an antidote to free improvisation. While there are doubts whether that is correct, what is your opinion on the following: can performing/interpreting somebody's music be compared with making it on the fly, in terms of the required amount of creativity and enjoyment?

BG: I personally enjoy the challenge of interpreting music— different disciplines are called for. Naturally, the creative aspect represents a smaller percentage of the overall commitment, but other factors compensate— not least the reward of getting inside a composer's music.

AAJ: The ability to improvise has seemingly become a creativity standard for any modern musician. Is domination of improvisation some sort of cultural trend or real necessity in the genesis of European and American culture?

BG: The ability to create music through improvisation represents a kind of liberation of thought and action. Paul Lytton has often taught aspects of improvisation to business people who are very often locked into a methodology. Discipline is also important, so I hope that improvisation—and it can come in many forms—will establish itself within the consciousness of all stratum of culture and society.

AAJ: What tendencies, in your opinion, sound the most promising?

BG: I really cannot read the future. Only hope is a currency that can be circulated, and musical survival is at the mercy of many contingencies. As I said earlier, the young voices will represent a continuum, but it may be different from what we have been involved in. It's a short answer here.

AAJ: What do you think about jazz in XXI? Is jazz "dead"?

BG: 21st century jazz? Many of the old guard are still active, and there are musicians out in the world that possess great technique and imagination. We can hope (I say this word again) that there is a continuity of ambition and realization to keep the momentum going. It is for sure that the popular media will not help in disseminating the music. Many times the "jazz is dead" mantra has been pronounced. We uttered the same words many years ago, and it will be reiterated many more times. It's a kind of protection to justify a new direction. It is in one way correct but in another way not so. The diversity of improvised music will be the key to the future, but it may not fall under the classification of "jazz." But then again, some music will.

BG: 21st century jazz? Many of the old guard are still active, and there are musicians out in the world that possess great technique and imagination. We can hope (I say this word again) that there is a continuity of ambition and realization to keep the momentum going. It is for sure that the popular media will not help in disseminating the music. Many times the "jazz is dead" mantra has been pronounced. We uttered the same words many years ago, and it will be reiterated many more times. It's a kind of protection to justify a new direction. It is in one way correct but in another way not so. The diversity of improvised music will be the key to the future, but it may not fall under the classification of "jazz." But then again, some music will. AAJ: Can we expect great developments in modern classical music?

BG: I am not really in a position to comment upon this, since my knowledge is limited as to the latest manifestations in modern music. I read of names that occupy journalists' and critics' faculties, but maybe my own busy musical life has kept me a little distant from the latest trends. I am sure, however, that there are exciting things happening out there.

AAJ: How did you meet Mats Gustafsson?

BG: That was solo in '92 in Stockholm. I think that's the answer you need, and the rest is history.

From left: Mats Gustafsson, Barry Guy

AAJ: Your musical backgrounds and personalities seem very different, but you achieve perfect harmony and understanding. How does it work? How does a spontaneous acquaintance develop into a long-term work relationship?

BG: We both love good music in general and performing in particular. We seem to possess the same energy levels, which feeds our curiosity and excitement of creating a musical dialogue.

AAJ: Please tell us about your collaboration with Lithuanian musicians.

BG: It is always interesting to meet a new group of musicians. On the occasion of my meeting with Lithuanian musicians, it was pleasurable to note that the language of improvisation resides powerfully in many parts of the world. Our collaboration had all of the attributes of informed and creative musicians. Listening to the recording of our collaboration reaffirms why we so enjoy being part of this world music.

AAJ: Did you have any expectations coming to play in Vilnius, and were they met?

BG: Mats Gustafsson informed me prior to my visit that I would enjoy the project. He was correct, and needless to say, the hospitality and support was impressive. The Lithuanian musicians were friendly, aware and creative—a really fine combination.

AAJ: What are your plans for the near future, and do they include creating more orchestral music and further experiments in this direction?

BG: Plans are many and cover a wide area of music. Currently I am rewriting "Radio Rondo" for the Barry Guy New Orchestra—the piece, of course, was composed for Irene Schweizer and the LJCO. Also for the BGNO, I will write a piece that features Maya Hamburger with the guys: a tricky balancing act matching the fragile baroque violin with heavyweight saxophones, brass and percussion—fascinating, nonetheless.

For our duo, I will compose a series of seven pieces that will be generated out of the work of New York artist Elana Gutmann, with the first performance slated for February 2010. We will then record a new duo album. Also in 2010, there will be two unusual projects—one for the Vancouver Festival, a collaboration with animator Michel Gagné, and improvising musicians will be premiered. Also I have been commissioned to provide a set of musical interventions into the opera "Dido and Aeneas" by Henry Purcell, using improvising and baroque musicians. That's quite a lot to be getting on with.

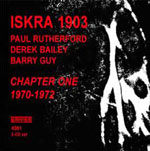

Selected Discography

Diatribes and Barry Guy, Multitude (Cave12, 2010)

Savina Yannatou/Barry Guy, Attikos (Maya Recordings, 2010)

Ken Vandermark/Barry Guy/Mark Sanders, Fox Fire (Maya Recordings, 2009)

Barry Guy/Mats Gustafsson, Sinners, Rather Than Saints (NoBusiness Records, 2009)

Barry Guy/London Jazz Composers Orchestra/Irène Schweizer, Radio Rondo/Schaffhausen Concert (Intakt Records, 2009)

Agustí Fernández/Barry Guy, Some Other Place (Maya Recordings, 2009)

Barry Guy/Marilyn Crispell/Paul Lytton, Phases Of The Night (Intakt Records, 2008)

Glasgow Improvisers Orchestra with Barry Guy, Falkirk (FMR Records, 2007)

Evan Parker/George Lewis/Barry Guy/Paul Lytton, Hook, Drift & Shuffle (PSI (UK), 2007)

Jacques Demierre/Barry Guy/Lucas Niggli, Brainforest (Intakt Records, 2006)

Evan Parker/Barry Guy/Paul Lytton/Philipp Wachsmann/Joel Ryan, Free Zone Appleby 2004 (PSI (UK), 2005)

Barry Guy/London Jazz Composers Orchestra, Study II/Stringer (Intakt Records, 2005)

Maya Homburger/Barry Guy/Pierre Favre, Dakryon (Maya Recordings, 2005)

Barry Guy/Marilyn Crispell/Paul Lytton, Ithaca (Intakt Records, 2004)

Barry Guy/Evan Parker, Birds And Blades (Intakt Records, 2003)

Tri-Dim + Jim O'Rourke and Barry Guy, 2 of 2 (Sofa 2002)

Barry Guy/London Jazz Composers Orchestra, Three Pieces (Intakt Records, 1997)

Mats Gustafsson/Barry Guy, Frogging (Maya Recordings, 1997)

Barry Guy/Paul Plimley, Sensology (Maya Recordings, 1997)

Evan Parker/Paul Dunmall/Barry Guy/Tony Levin, Birmingham Concert (Rare Music, 1996)

Mats Gustafsson/Barry Guy/Paul Lovens, Mouth Eating Trees And Related Activities (Okka Disk, 1996)

Marilyn Crispell/Barry Guy/Gerry Hemingway, Cascades (Music And Arts Programs Of America, Inc. 1995)

Evan Parker/Barry Guy, Obliquities (Maya Recordings, 1995)

Barry Guy/London Jazz Composers Orchestra, Portraits (Intakt Records, 1994)

Barry Guy And the Now Orchestra, Study, Witch Gong Game (Maya Recordings, 1994)

Barry Guy solo, Fizzles (Maya Recordings, 1993)

Barry Guy & London Jazz Composers Orchestra with Irène Schweizer, Theoria (Intakt Records, 1992)

Photo Credits

Page 1: Courtesy of Barry Guy

Page 2: "Nasca Lines," excerpt by Alan Jones

All Other Photos: Dmitrij Matvejev

Tags

barry guy

Interview

Maxim Micheliov

Lithuania

Vilnius

Mats Gustafsson

Liudas Mockūnas

Gary Peacock

Scott La Faro

Charles Mingus

Michael Mantler

Kenny Wheeler

Paul Rutherford

Howard Riley

Tony Oxley

Globe Unity Orchestra

Derek Bailey

Paul Lytton

Irene Schweizer

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.